Before the invention of plastics, glass and paper were used to produce black and white photographic negatives. Glass plates with gelatin emulsion were produced from the late- nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. The transparency of glass made the plates very popular among photographers. This allowed them to produce very sharp and detailed images in a short time—less than a second. Glass is very fragile and breaks easily while traveling, printing, or in storage, so it is very common to find broken plates in photographic archives from that time.

The performing arts holdings at the Harry Ransom Center contain an important collection of glass plate negatives dating from between about 1890 to about 1920, depicting images of theater productions and Broadway theaters. Among them are images acquired by Albert Davis, a collector of theatrical memorabilia whose collection came to The University of Texas at Austin in 1956. The conservation department examined and is currently treating the broken plates from the Albert Davis collection, making them safely usable for researchers.

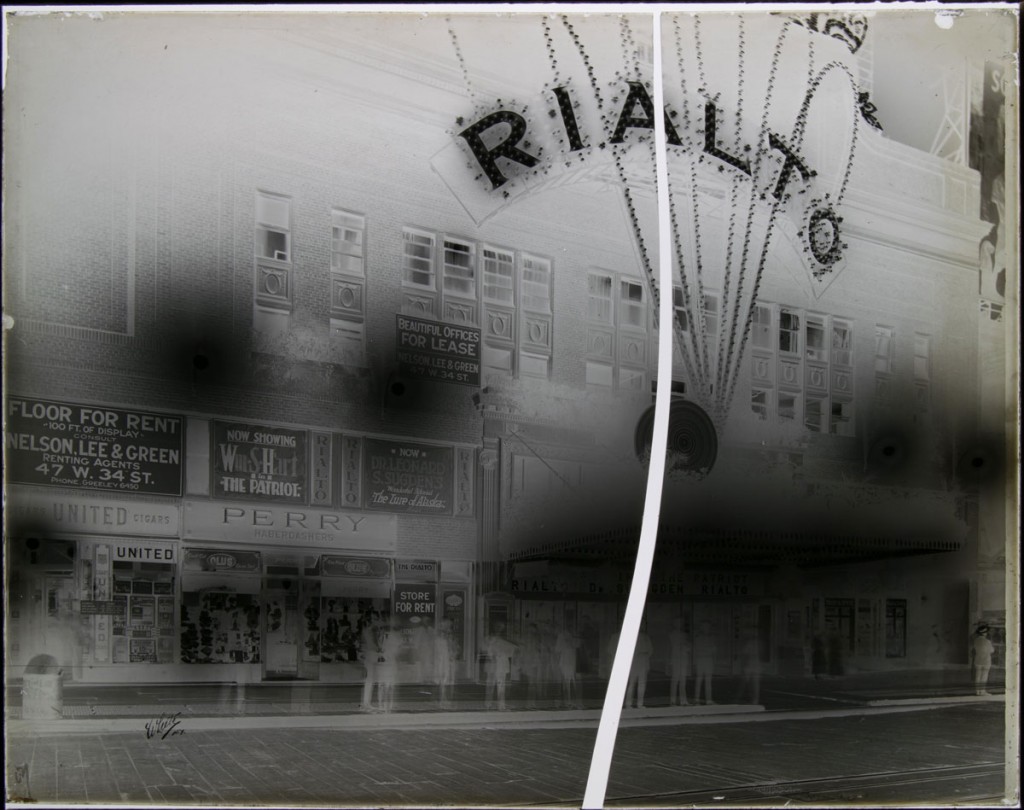

One of the mended plates is an image of the Rialto Theatre, a movie palace once located on Broadway and 42nd Street in New York City’s theater district. Built on the former site of Oscar Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre, the Rialto opened on April 21, 1916. The original theater was demolished in 1935, when a new, smaller, Rialto, in Art Deco style, was built in its place.

This image of the Rialto Theatre was taken around 1920 by White Studio, a prominent theatrical photography studio in New York City that was active from 1905 to 1925.

The plate arrived to the photo-conservation lab broken in two pieces. As conservator of photographs, I examined the plate carefully and, after considering the stability of the emulsion and the image, decided to rejoin the fragments using an acrylic resin commercially known as Paraloid B–72. This resin does not interfere with the transparency of the plate, does not yellow with time, and is strong enough to keep the pieces of glass together. This will facilitate future handling, access, and the safe housing of the plates.

To start, I first cleaned each fragment to remove accumulated dust, dirt, and oily residues on the glass. Then, I aligned the two pieces horizontally with the glass side facing up, matching the image along the crack. Once it was perfectly aligned and secured, I applied the acrylic resin along the crack using a steel wool swab, which allowed me to use very small amounts of adhesive. The adhesive traveled through the crack by capillary action, pulling the required amount of adhesive with minimal excess. It was left to dry for a couple of days, and, finally, I cleaned any residue of adhesive with a small amount of solvents.

As a final step, to prevent further damage each plate gets a custom–made box, known as a sink mat. The sink mat is a box constructed of archival–quality corrugated board that supports the glass and protects the photographic emulsion, while also allowing access to the plate.

Glass plate negatives remain useful even if broken, as they can be printed again on photographic paper. Preserving these photographic materials greatly benefits future generations of researchers interested in the practice of photography before the digital revolution.

Related Content

Read more about conservator Diana Diaz in our Meet the Staff series

Read more posts in our Meet the Staff series

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email.Subscribe today.