August 8, 2020

Cassandra Donnelly is a PASP fellow and PhD student in the Classics Department at the University of Texas. She is writing her dissertation on the Cypro-Minoan script. She thanks the Archaeological Institute of America for funding her travel abroad. Read her first travels in Cambridge last year here.

Settling In

When I set off on my year abroad in May 2019 I wasn’t expecting to fall in love. Least of all with Cyprus. I had gone there in late July of 2016 for a week’s work in the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia. I had just been excavating in the small town of Pylos, Greece, and stepped off the plane, bone-tired, to a Deloitte billboard. That first impression stuck. Cyprus is like Greece on free market steroids, I thought to myself with contempt. In addition to its capitalist excesses, Cyprus was incredibly, incredibly hot. From the airport, I arrived to an empty Nicosia. Everyone had already fled its heat, as they do peak-summer every year, for the cooler air of the Troodos mountains. I wandered through old Nicosia’s strange clash of byzantine and bling, exhausted and near delirious from the heat. Every day I would stop by the museum, ragged and defeated, desperately hoping my permit had been received and that today would be the day they would let me see the clay balls and I could finally leave. Little would I have believed then that, when faced with the decision in March 2020 to quarantine at home in the US or Cyprus, I chose to quarantine in Cyprus at the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute (CAARI). Because I had fallen in love.

What I love about Cyprus is embodied in its twofold coffee tradition. On the one hand, there is the Cyprus coffee (also known as Greek coffee, or Turkish coffee, but that’s another blog post) tradition and, on the other hand, its espresso coffee tradition. Cyprus coffee is homey. At least for younger people it’s not something you frequently order at a café. Instead, you make it at home for your loved ones and you make it for guests. It’s about hospitality. Cyprus coffee also has a dimension of the mystical to it. How its coffee pours from the container (the brika) as one single mass to form three perfect tiers of foam, coffee, and sediment, in each cup. How the sediment can, in the hands of a fortune teller, come to show you your future. Homey, hospitable, a little bit mystical. In other words, Cyprus. But those three words are not the complete picture. They are complimented by the excesses of Cypriot espresso culture. There are eleven coffee shops in a two-block radius of CAARI. Eleven. It’s not even in the city center. Cypriot coffee shops are not workspaces, but social spaces. They’re places to talk or play tavli with friends for hours and hours on end. The overall coffee standard is high and shops can be quite snooty to reflect this. I have an Italian friend who, in true Italian fashion, says Cyprus is the only country outside of her homeland where she will buy an espresso out. And don’t forget the Frappés and Freddos. Whipped, cold coffee drinks, first made popular in Greece, that are frankly silly drinks, but utterly necessary once the summer temps set in. Homey, hospital, mystical, on the one hand, and social, snobby, and necessarily silly on the other. Yeah, that’s Cyprus.

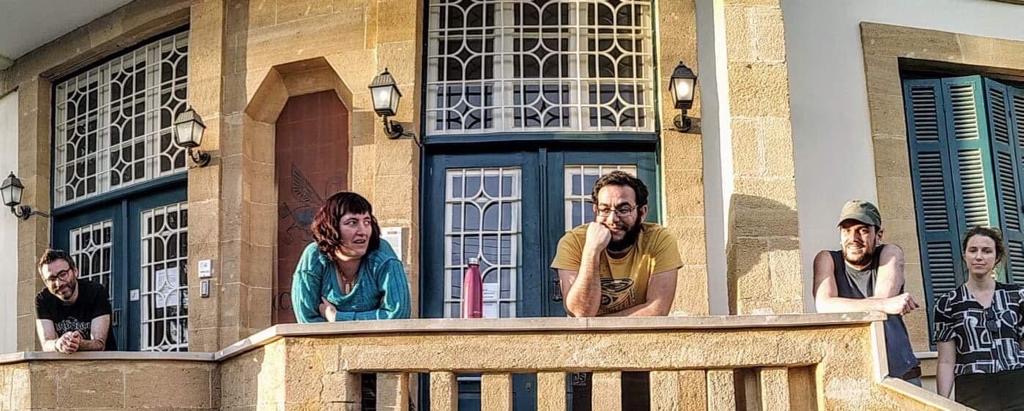

It took 7 months of living in Cyprus and the quarantine to learn how to make Cypriot coffee. Cyprus coffee is a home tradition and I was living in a hostel, after all. The magnificent Photoulla, who took care of CAARI and became my surrogate grandmother, lovingly made Cypriot coffees for us every Wednesday for CAARI’s “coffee hour.” But still I didn’t learn how to make the coffees for myself. I was contended being served. It wasn’t until Photoulla was forced to stay home by the pandemic that I, lazy boarder that I was, took to making my own Cypriot coffee and, by extension, making CAARI my home.

Learning Cypriot

The key to making Cypriot coffee is patience. At least that’s what the internet directions said. Patience, υπομονή, was one of the quarantine taglines (it’s also good advice for dealing with the Cypriot civil service). It’s the word Cypriot singer Alkinoos Ioannides used to end the comfort ballad he wrote for quarantine called “Together Again,” which he sang along with his school age daughters. We will be together again. Patience. According to Stelios, CAARI’s Cypriot boarder, the key to making Cypriot coffee is to stir it vigorously three separate times. Once when you pour the finely ground beans into the brika, once when the grounds have just begun to heat, and once more just before the concoction starts to boil. It takes persistence. Patience and persistence. The final result, if you’ve done it right, produces the strict hierarchy of foam, coffee, and sediment in each cup.

I love making Cypriot coffee. But it took a while, patience, to get the hang of it. The first time I made it for my quarantine roommates I had not stirred it sufficiently. As I learned, Cypriot coffee needs to be stirred just a little bit more than you think you does. Persistence. It requires persistence. That first batch of Cypriot coffee, though. My roommates’ eyes bulged from their heads as they slurped up the sediment that had rebelled from its place in the cosmic order at the bottom and floated up into their lips. Eventually—through patience and persistence, dare I hammer home the theme further—I learned to make a good cup of Cypriot coffee. As an American, especially one from the northeast, patience didn’t come easy. Nor persistence, for that matter. But I came to love the process of standing, stirring, and serving. I especially like the serving part. Making hot cups of afternoon coffee to share with my roommates, giving the cup with the best foam to the nicest roommate (just kidding) and saving the cup with the worst foam for myself. Reminding myself what the proper hierarchy should be. A meditation on hominess and hospitality.

Telling Fortunes

About six weeks into lockdown, a sister of a friend of one of our quarantine roommates offered to read my fortune. Her instructions were as follows. After drinking a cup of Cypriot coffee, flip the coffee cup onto a saucer covered with a paper towel and leave it there for twenty minutes. After the twenty minutes, transfer the cup to a second saucer, this one uncovered, for another ten minutes. This procedure lets the sediment harden onto the sides of the coffee cup, encrusting it with one’s future. My fortune, according to her, is as follows:

“A project she has in mind will be successful. She will take money soon. A person doesn’t love her. He wants to hurt her with words. Cassie sits together with the person who doesn’t love her. Maybe in an office, we don’t know. She is sad for the person but that person will come to find her and say good words to her. They will travel to meet each other (there is a road). She will go for coffee with the person but not very soon.”

We all agreed that the reading felt a little mystical. Every day I sat together with Stelios in our office, the library. And aside from teaching me how to make a Cypriot coffee, he never said good words to me. About this we all agreed. But where would we travel to meet and where would we get coffee? For my part, I want to return to Cyprus one day. I can think of no better country to get coffee in. I hope that’s the country the fortune is talking about. A return to the homey, hospitable and kind-of-mystical country of Cyprus. I also hope the project it’s referring to is my dissertation project. After a year of working on it, including four months of collecting data at the Cyprus Museum and another four months of library research at CAARI, it’s time to start writing. In the meantime, I can hope my future comes to pass.

Updated on August 8, 2020 by Garrett R. Bruner. garrettbruner@utexas.edu