by Tom Palaima

Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics

Director, Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory

In December 1946, in a clear sloping hand, on super-thin post-war paper, Kober wrote Sir John Myres: ‘I must confess, strong as the statement sounds, that I would gladly go to the ends of the earth if there were a chance of seeing a new Linear Class B inscription when I got there.’

—Alison Fell, The Element -inth in Greek (2012) p. 3.

During my recent research, seminar and lecture stint at University of Copenhagen’s Centre for Textile Research in September 2022, I had stretches of time completely to myself for the first time in many years. In my reading and thinking, I came across Henry James’s summing up of the world in which he and now we live:

“Life is, in fact, a battle. Evil is insolent and strong; beauty enchanting, but rare; goodness very apt to be weak; folly very apt to be defiant; wickedness to carry the day; imbeciles to be in great places; people of sense in small, and mankind generally unhappy.”

And just today in looking up a source concerning the condition of people who are poor in our country, I found, in an op ed piece I wrote in late December 2018, this quotation from Jeff Dietrich’s little-read book Broken and Shared: Food, Dignity and the Poor on Los Angeles’s Skid Row in which he sums up succinctly and insightfully the life of Jesus:

The story of Jesus “is not a success story; it is, rather, a failure story. Jesus was betrayed by his best friend, denied by his lead disciple, deserted by his followers, and ridiculed by his once-adoring crowds.”

It is almost impossible in these days of unfettered capitalism to communicate what crystalline pure devotion to modest and unassuming lives of the mind scholars like Alice Kober and Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. had and how that devotion sustained them and gave their lives a central posited purpose. They had egos, but they were sublimated to the greater good of their chosen field of research and the goals that they set within it. They were scholars through and through and aware of their deep responsibilities to other scholars, past, present and future, and to the societies in which they lived, and especially to their students.

This is why devoting a display to the meticulous and voluminous work notes and scholarly correspondence of Alice E. Kober in Australia’s Macquarie University History Museum’s exhibit on Mysteries Revisited, From Ancient Codes to Comic Culture is reverent and heartwarming and important. These materials, which are not only Kober’s Lebenswerk, but arguably the very essence of her life, at several crucial points could easily have been lost forever.

In the ten years (1973-1983) I worked closely and often in the two offices that Kober’s eventual closest collaborator Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. occupied at the University of Wisconsin Madison, I never even saw the boxes in which Kober’s materials were stored. Kober shortly before she died on May 16, 1950 told her brother that when she died her scholarly papers and notes should go to Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. This included what was in her house in Brooklyn and some materials in the University of Pennsylvania Museum that were there because of her and John Franklin Daniel’s dream of setting up an Aegean scripts study center. His death in 1948 at the age of 38 snuffed out the candle of their dream.

Kober, with whom her mother was pregnant when they came to Ellis Island in 1906, knew the hardships of a newly arrived immigrant family trying to make a life in their new world. She lived abstemiously throughout her life. To attend Hunter College and excel at everything except physical education, and then obtain a Ph.D. at Columbia University and win a teaching position at Brooklyn College must have seemed to her and her mother a true dream come true. Attainments beyond fantasy for Alice in the Old World. She did her utmost to be a dutiful daughter to her mother and to be a fully helpful colleague and an inspirational and supportive teacher (teaching a 5:4 course load, overseeing undergraduate clubs and even learning Braille and then typing exams in Braille for Brooklyn College students).

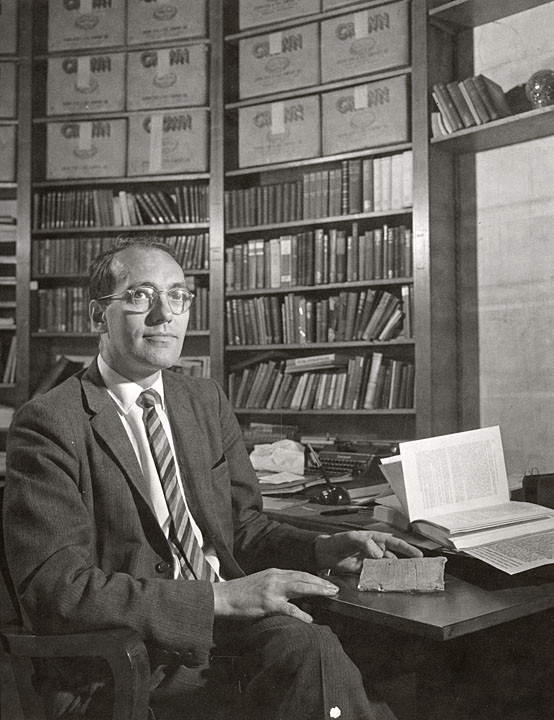

In my thirty-eight years of knowing and eventually truly loving Emmett Bennett as a second father, not just as a Doktorvater, and even caring for him, when he was in his eighties, as I did my own father, for an extended period here in Austin, I never heard him utter a single word of complaint about anything. Utterly remarkable. Pun unintended, but there it is, and Emmett would have appreciated it.

Occasionally Emmett would be annoyed by yet another ill-informed or misguided attempt to ‘read’ Linear A or the Phaistos Disk, but even then, his written demonstrations of the errors of their ways were just that. And in speaking to me, he stuck to pointing out their flaws in establishing and reasoning from the essential data. His teaching manner was not for everyone, but it was perfect for me. Exploring perplexing problems together. Delighting in new perspectives. Truly caring about precise details. And suffering the fool writing this gladly.

Music, walking (when he could no longer safely bicycle) and observing the day-to-day world around him, working NY Times crosswords and Manchester Guardian cryptic crosswords—both of which amused him for phenomenally short periods of time most days, pondering and often resolving problems with Mycenaean texts, and occasional personal interactions with colleagues, students and friends—mostly one and the same—occupied his days in his later years. He was disarming and cared not for any academic politics or gossip, old or new. He was kind and considerate, open-minded and tolerant, albeit wedded to his love of classical and choral music (including church music despite his atheism) and Gilbert and Sullivan. Graduate students who helped him on and off campus truly fell in love with him, too. My son’s mother did not hesitate for even a split second when I said that I would like for us to name our only child Emmett. I am grateful to her for that. Our son, after a spell of going by one of his simpler middle names, once he was in college and now as an adult goes exclusively by the name Emmett. He makes a name for himself now as an artist and musician, intuiting relationships between electricity and the spirit in his work The Church of the Electric God, recently on exhibition in New York.

Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. (b. 1918) expressed a true fondness for Michael Ventris (b. 1922), pointing out that they shared the same birthday (July 12) four years apart. And Emmett spoke of how in Michael’s last year of life (1956) at the first Mycenological Colloquium at Gif in April 3-7, they shared and commiserated with one another about some of the same significant personal problems and dilemmas. Yet he never once expressed any disappointment that Michael had gotten to the Everest of decipherments first. Nor did he speak critically of the means Michael used to get there. Not even a hint of a single sour grape.

Their shared passion was truly shared. It made them what Diogenes Laertius preserves for us as friends in the Aristotelian sense of the term: ‘one soul residing in two bodies’ (μία ψυχὴ δύο σώμασιν ἐνοικοῦσα).

So much for two of the three legs of the decipherment and central PASP tripod.

We are speaking here of the third, and perhaps the sturdiest and most supportive leg, Alice E. Kober (1906-1950). In her adulthood, Kober had two soul mates of whom we know. From age twenty-six right up to the week before she died at age forty-three, Kober’s life was largely given over (after completing her Ph.D. in 1932 on color terms in Greek poetry) to her early announced objective (when graduating from Hunter College in 1928) of ‘deciphering Linear B’, to which she devoted every spare moment in her busy days of teaching at Brooklyn College and caring for her own aged mother.

The two soul mates, with whom Kober corresponded and cautiously brainstormed, during the last decade of Kober’s too brief life, were Johannes Sundwall in Finland (1877 – 1966) in his sixties into seventies at that time and John Franklin Daniel III (1910 – 1948) at University of Pennsylvania. As we have mentioned, Daniel’s tragic early death put paid to their plans to establish a center for research in Aegean and Cypriote scripts at University of Pennsylvania. For the depths of their shared interests and Daniel’s strong championing of Kober in an age when women in academia had a very tough time of it, see the wonderful write up by PASP’s own Cassandra Donnelly, the world’s current expert on Cypro-Minoan script, on the CREWS Web site.

Eventually Kober and Bennett developed a strong and mutually beneficial rapport and worked fully cooperatively toward solving the complicated problem of establishing a standard signary of characters of the script—no easy task especially when the tablets themselves were not available for autopsy—that would allow for publishing the texts of the Knossos and Pylos tablets soundly and in a way that would be useful to scholars worldwide.

Impediments and obstacles were many. These included the devastated economic conditions in all countries of the world except the USA and especially in post-war England, which was losing its empire and had suffered the destruction of a million homes during the German Blitz of 1940-41. The resources of the Clarendon Press at Oxford were extremely limited and this made this eminent academic publisher reluctant to abandon truly outdated sign lists devised by Sir Arthur Evans. The continuing civil war in Greece kept museum collections closed and made travel dangerous until 1950. The general unconcern of the scholarly world in inscriptions that had kept their secrets to themselves for so long and that were thought, widely, to have nothing to do with the Greek language made focusing on Linear B professionally foolhardy. As an aside to the last: I was warned by four prominent scholars at the American School of Classical Studies in my first fellowship year (1976-77) that doing a dissertation on Linear B would be a death knell for my future career—it nearly was.

Kober, with her many years of acquiring diverse ancient languages in summer linguistic institutes, held to her firm conviction that no sound work could be done until the standard sign system and any regional or chronological variants were established and as many accurate texts as possible were correctly transcribed according to this system. Accordingly, she did her utmost during her last four years of life to help Sir John Myres complete the edition of the Knossos tablets that Sir Arthur Evans had started and entrusted upon his death to his (Myres’s) care. Kober was adamant that they should make every revision that her and Bennett’s increased knowledge of the script and tablets dictated. This was not to be in her lifetime and really never was to be in the history of Linear B scholarship.

Scripta Minoa II when it appeared in 1952 was not up to date. Yet its drawings and photographs and much of its surrounding information formed together a significant scholarly advance. But it was a text of the 1930’s and not the 1950’s.

Susan Lupack, senior lecturer, Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University, has written here an account of the exhibition clearly and understandably partly out of gratitude for our long years of mentor-student interaction. Our relationship now, too, has been transformed into friendship and has also engendered my own sense of wonder at her tremendous and diverse achievements as a teacher, scholar, field archaeologist, parent and highly principled human being. She speaks of Garrett Bruner and me making the Kober portion of the exhibition at Macquarie University in Australia come to be.

Sensu stricto she is not wrong. We are the immediate causes. Garrett and I spent long hours selecting materials and then investigating how to pack and ship them. They are irreplaceable. Eventually I spent hours and hours at a forbidding DHL ‘office’ in the Austin airport freight area trying to figure out how we could safely and economically ship our precious materials to Australia in such a way that they would not get hung up in customs and that their contents would not require opening and inspection, which would have been disastrous. DHL has no category for archival papers. As I discovered to my regret, any use of the term ‘value’, as in ‘of historical value’, immediately kicks in ‘insurance’ concerns by DHL and parallel concerns about customs authorities. Fortunately, I had learned from my postal worker father to wrap packages so that they could survive a nuclear detonation, a tidal wave, sinking in the ocean or an attack by alligators or birds of prey.

But there is a long list of PASP archivists over a thirty-year period and thirty-six years of PASP graduate and undergraduate assistants who have worked on all facets of PASP’s activities and especially on preserving and making available to the larger world—now even substantially electronically—the correspondence and research materials of Alice Elizabeth Kober and Emmett Bennett and Michael Ventris and their many collaborators.

The archivists, who have worked energetically and painstakingly and with true devotion and commitment over the last thirty years, are: Elizabeth Sikkenga (who also revived and served as chief editor of SMID from 1994-1999), Christy Costlow Moilanen, Sue Trombley, Zachary Quint (né Fischer), Sarah Buchanan (2014-2016) and Garrett Bruner (2017-2022). They all benefited directly or indirectly from funding from the Institute of Aegean Prehistory (INSTAP). By this I mean that INSTAP funds freed monies that were used to pay them for their services and purchase archival storage materials.

I remember Sue Trombley coming into my office crying from kind-hearted devotion when she discovered that Alice Kober, in cutting a Christmas-time invitation card down to a size appropriate for serving as a section separator in her cigarette-carton files, had made sure that the cartoonish drawing of Rudolph on its reverse side would remain intact and include the very tip of his red nose. Garrett Bruner is an impeccably trained and functioning specialist and a deeply learned humanist. I literally view him as a soul mate who understands that preserving and promulgating the PASP research archives is a sacred task in the long history of humanistic studies, especially in these days when universities are corporate training grounds and the study of the liberal arts has divorced itself from its roots in monasteries and monastic colleges like those at Oxford and Cambridge and now operates entrepreneurially and justifies its existence in terms of greater career dollar earnings.

Special recognition also should be given to graduate assistants like Dygo Tosa, who is now a full-time Latin teacher and teacher-leader of vision and support at Springfield Honors Academy in Springfield, MA. Dygo included archiving among the many jobs that he accomplished over several years. He literally kept the PASP ship sailing during a period of several years that were typhoon-like in overwhelming my own life’s ship. Graduate students—and a few undergraduates—have studied and precisely described all kinds of materials, both single items and discrete batches. They have also developed simultaneously a deep sense of obligation to keeping the wonderful resident spirits of all the scholars directly or indirectly present in PASP alive.

Students who worked in PASP the last four years will have to stand for those stretching back another three decades:

Kevin Lee (Spring 2018 to Summer 2018), Zoé Thomas (Fall 2018), Cassie Donnelly (Fall 2019), Michele Mitrovich (Fall 2019), Erin Brantmayer (Spring 2020), Jared Petroll (Spring 2020 to Spring 2021), Nicole Inskeep (Summer 2021 to Fall 2021), Maija Gierhart (Fall 2021), Amber Kearns (Spring 2022), Nicolas Larimer (Spring-Summer 2022), Autumn Greene (Fall 2022), Anthony Bronzo (Fall 2022).

In particular, I would like to mention a few early birds from the 1980’s and early 90’s: Jean Alvares, whose recent book explores the notion of the ideal in the Greek and Roman novel; Yuri Weydling, who retired in 2018 after 28 years of teaching Latin at the Baton Rouge Magnet High School in Baton Rouge, LA; Bruce LaForse, who is retiring in May 2023 from teaching Classics and ancient history at Wright State University; Philip Freeman, who did an M.A. on Linear A, and is now, many books later, Fletcher Jones Chair/Professor of Humanities at Seaver College Pepperdine University; and Kerri Cox Sullivan, who is now Publications Research Editor for the Sardis expedition at Harvard and did final production editing on the highly complicated Festschrift for José L. Melena in 2022.

Two writers who researched the life of Alice Kober, contributed valuable information and materials about her to the PASP archives and then wrote extraordinary books deserve special and conspicuous mention. The first is poet, author and artist / sculptor Alison Fell (1944 – ) (see also: https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/alison-fell). The second is author and former New York Times obituary writer Margalit Fox. They both came to understand Alice deeply and to love her. They both have done much to bring her back to life. They have given us Alice as a human being who had strong personal feelings about her life and work and an absolute commitment to those who were entrusted to her care as students or who trusted in her for her scholarly help.

In The Element -inth in Greek (Sandstone Press 2012 ISBN 10: 1908737026 ), Alison Fell uses the devotion of her central character Ingrid Laurie to Kober and her life’s work to take Ingrid from the UK to fictional versions of PASP and Sue Trombley and me in Austin, Texas and eventually to Crete where Ingrid’s knowing what Kober knew becomes crucial to bringing the events that are at the core of the narrative to a proper resolution.

Alison Fell’s writing is really first-rate and accurate in using close observations to construct characters from real-life models and to interweave doings in the present with events from Kober’s life and letters and her part in the marathon-length race to decipherment. You, as reader, learn things you should know about Kober and her inner self.

Alison also tracked down lots of what we know about Alice’s family’s first twenty years in New York and just missed by months being able to read Alice’s doctor’s files concerning the precise medical diagnosis of the illness that killed her.

Most endearing to me of all was Alison’s refusal to change her title, which preserves and celebrates the title of Alice’s unpublished monograph on the subject of pre-Hellenic loan words in the Greek lexicon, even though, as she reports, “every publisher balked at the title! Sandstone also wanted to change it to The Element … but of course I refused, and they conceded.”

Do read The Element -inth in Greek by Alison Fell and other books, poems and novels she has written or edited in her distinguished career.

The second writer is Margalit Fox, who worked with the Kober archives exhaustively and worked hard to get things right and tell Alice’s story to the world. Her book speaks for herself as well as for Alice and is extremely generous in its acknowledgments including to Alison Fell and invaluable UT staff members of the time like Matthew Ervin and Beth Chichester who not only made the trains run on time but kept them and their tracks in good repair and prevented the engineers and conductors from being driven mad by the kind of bureaucracies that gave birth to the Aegean linear scripts. Do read, too, The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code (Ecco Press 2013).

But most of all, if you are in Australia, go see Mysteries Revisited, From Ancient Codes to Comic Culture.

Finally and sincerely, Garrett’s and my great thanks to Dr. Martin Bommas and Dr. Josephine Touma for reverently handling and displaying the Kober materials and understanding the human dignity and grace that lie within them. And thanks from Emmett, Michael, Alice and John, too.