by Tom Palaima

Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics

Director, Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory

Ten years ago I wrote a feature piece for the Times Higher Education on mentors as a kind of endangered species (see PDF version here). In thinking back now on the nearly fifty years since I took my first graduate class in Classics, I think of two academic ‘men of God’ who deeply affected my outlook on life.

The first was my main ugrad mentor at Boston College (1969-73) and the teacher who introduced me to the Greek Bronze Age. David Gill, S.J. had studied at Harvard, completing his Ph.D. under Sterling Dow on Greek Cult Tables. Dow, mainly a classical epigrapher and historian, had developed an interest in what were then called Minoan inscriptions after the Ventris decipherment of the Linear B script in June 1952. As a consequence, Gill’s two-semester ancient Greek history course spent many weeks on Aegean prehistory, during which I reported on what then was early scientific research on the volcanic eruption of Thera. Actually, I contracted mononucleosis that semester and by the time I recovered, Gill suggested that instead of writing up a report, I deliver a whole class lecture on the readings I had done. I agreed at first, thinking that this would be easier. Then I realized I had to present a 50-minute lecture to an audience of about 65 students, most of whom I did not know. I was so terrified I memorized the entire talk. How I avoided a relapse into exhaustion illness I do not know.

In Gill’s class we also read William McDonald’s inspiring classic Progress into the Past (1967). Right now I am using it in AHC 378 History of Greek Prehistory. Another example of Gill’s ingenuity with regard to making up course work now comes to mind. In spring of my freshman year (1970), we missed many weeks because of the general student strike sparked in part by government lies about the bombing of Cambodia. In order to make up for those missed weeks over the summer, Gill set me to translate large parts of Vergil’s Aeneid. I have my doggerel English poetic version somewhere in notebooks.

Looking back now over a half century, what was most special about Fr. Gill was that, like Fr. Tom Bermingham who was later a revered colleague of mine at Fordham University (1980-86), Gill had internalized Matthew 5-7. This part of the gospel of St. Matthew contains the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer. But it also contains prescriptions, straight from the mouth of Jesus and yet nowadays forgotten or ignored, about how to conduct yourself when doing good unto others, including even making charitable donations. In strict accordance with Jesus’s advice, neither David nor Tom ever drew attention to their active commitment to the poor, the needy and the forgotten in our society. Their behavior is consistent with a behavior of that all but extinct species in our age of hyper-capitalism. I refer to the anonymous donor. Here is what Jesus says in Matthew 6: 1-4:

Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them. If you do, you will have no reward from your Father in heaven.

2 “So when you give to the needy, do not announce it with trumpets, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and on the streets, to be honored by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. 3 But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, 4 so that your giving may be in secret. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.

In the classroom and in the great tutorial seminars he conducted for us, Gill was focused on scholarly matters. In my senior year, Gill and four of us students read through Grote’s History of Greece during the fall semester and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in the spring semester. We met weekly on Wednesday evenings for dinner at the Jesuit house and then two hours afterwards of discussion of the reading at hand. This was the first time I became aware that one could “be an intellectual” in the normal course of life and not just in the classroom: at the dinner table or afterwards over sherry or for that matter anywhere at all.

Eight years later while teaching at Fordham University, I got to know Tom Bermingham, S.J. Bermingham had become famous for his scenes in the movie The Exorcist where he played a role as president of Georgetown University offering advice to Father Damien Karras, the young priest who has to grapple with the demon possessing the young girl Regan MacNeil while himself having a crisis of faith. Bermingham was also expert on the subject of exorcisms and had served as a mentor to fabled—in my mind now infamous—Penn State University football coach Joe Paterno. What is remarkable about Bermingham, too, is that he would fit in teaching a course on Homer with his holy work of settling newly arrived Cambodian refugees in ‘bad’ neighborhoods in the South Bronx and shepherding them in their adjustment to American culture. Their adjustment was almost always successful because of Tom Bermingham’s ingenuity and indefatigable work as ‘good shepherd’ on their behalf. None of that work gets in Bermingham’s extensive Wikipedia profile. Like Gill’s work, it was done “off the record.”

This poem by Father Gill I think speaks well to the souls of both of these remarkable human beings whom I am very glad to have known in my early days. I am sure they reinforced my inclination to work at different times with veterans, with poverty-level adults trying to go back to school, with youths and parents confronting violence and to devote so much time to addressing educational and political problems and general social norms and values in my twenty years of serious public intellectual writing. I can still feel the invitingly conspiratorial way Tom Bermingham would talk, while dragging on a cigarette, about his movie work and about Homer, and on rare occasions about his refugees, their hardships and successes. “Did you ever consider this, T?” I can still hear Dave Gill’s clear and comforting voice, offering advice by posing questions that I would take away and think about. Both men left with me a residue of goodness that has always warmed me and provided a flickering light “in the dark and cloudy day.” They are proof to me of Viktor Frankl’s contention that happiness, in our modern sense, cannot be pursued, but is itself the rare residue of working hard to do good in and of itself.

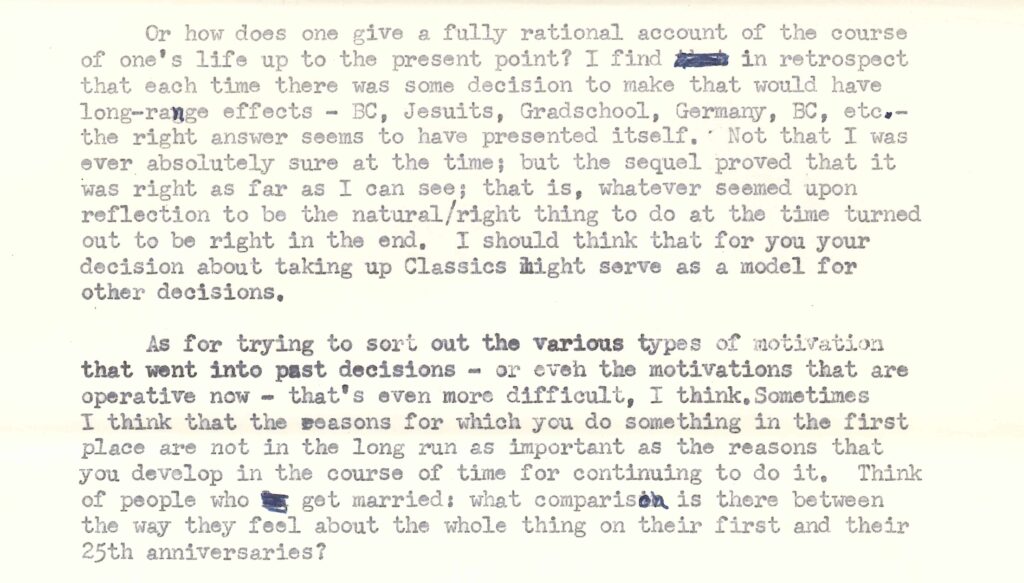

David Gill, S.J.: In My Own Words. 1992

https://epublications.marquette.edu/conversations/vol2/iss1/14/

“ I’m a Jesuit in the university,

a teacher, a scholar, a humanist

trying to study and teach history

from the point of view of the losers

rather than the winners,

the poor rather than the rich,

the peasants rather than the princes.

I think the modern Jesuit, and Christian,

is challenged to take a leap of faith

and believe that God is to be found

not only in the beauties of the divine

and human creation but also in the lives

and sufferings of the poor and outcast

members of the human race.

As a teacher, as a scholar in the humanities,

and as a Jesuit, I pursue an understanding

of what Dostoyevsky’s Father Zossima calls

‘active love’ – severe and terrifying,

entailing hard work and tenacity,

but close to ‘the miraculous power of the Lord.’ ”

David Gill SJ Lecturer in Classics

Then Rector of the Jesuit Community College of the Holy Cross

Now retired

For more of Tom Palaima’s story, both professional and personal, visit his recently updated faculty profile page.