In light of everything that is going on in our country right now, I briefly considered cancelling plans to publish this post, which has been on our planning calendar since last Fall. The DAC blog team is working on other posts related to protests and social movements around racial justice and the history of systemic and violent racist oppression in the United States. Those posts will go up as soon as we are able to get them finished.

While we all grieve the violent and needless deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis, MN; Michael Ramos in Austin, TX; Breonna Taylor in Louisville, KY; Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, GA; and Tony McDade in Tallahassee, FL, it is my hope that remembering the incredible life of Josephine Baker on the 114th anniversary of her birth will provide another avenue today for honoring black lives and black legacies in the United States.

Black lives matter.

Early Life

At age 13, Baker ran away from home. She began working as a waitress in a club and married a man named Willie Wells, whom she separated from after only a few weeks, though technically the marriage was never legal due to Baker’s age. She performed in clubs and on the streets until she began touring the United States with an all-black theatre troupe based out of Philadelphia. At 15, she married Will Baker, and though this marriage lasted only a little longer than her first, she kept the name Baker for the rest of her life.

Fame

Baker’s comedy skills provided her with increasingly successful performance roles and an undeniable place in the Harlem Renaissance. In 1925, she was invited to join La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris. She was 19 and already one of the highest paid performers in vaudeville. In Paris, her comedy and dance routines were celebrated, but it wasn’t until her performances turned to the more exotic that she truly achieved the international fame she is known for.

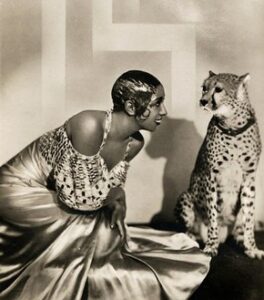

Baker embraced the exotification at the time, regardless of how she may have felt personally about her “Africanized” burlesque performances. She became a larger than life persona, even adopting a pet cheetah, which she named Chiquita, and walked on a leash with a diamond collar.

In 1927, she became the first black woman to star in a movie, Siren of the Tropics, a silent French Film. This debut was followed with two “talkies,” Zouzou in 1934 and Princess Tam Tam in 1935.

Baker’s fame continued to skyrocket. She expanded her repertoire and her performances matured until she was one of the highest paid performers in the world.

Baker was an American expat in Paris at the same time as Gertrude Stein, Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, all of whom, along with other Jazz Age artists including Picasso and Colette, considered Baker as a muse.

She returned to the U.S. a couple of times, but was frustrated and disgusted at the racism she experienced. In the time of McCarthyism, she was accused of communism, and hounded by both the FBI and the CIA.

Baker married her third husband, a Frenchman, in 1937. Like the other marriages, this one didn’t last long, but it did provide Baker with the opportunity to become a French citizen, after which she renounced her American citizenship.

Over the years, she had many lovers of all genders, including a nearly 10-year relationship with her manager and a Sicilian count, Pepito Abatino. While Baker never labeled her sexuality, she did have affairs with women throughout her life, including Ada Smith, Colette, and possibly Frida Kahlo.

Espionage

When World War II broke out, Baker remained in Paris, which by then, she considered her country. Baker worked as a nurse for the Red Cross. When France became occupied, Baker joined the French Resistance, smuggling information across enemy lines and hiding weapons and refugees at her chateau. Her international performances provided Baker with a unique opportunity. She would perform and attend parties at the Italian Embassy and then pass along any information she learned to the resistance, written in invisible ink on her music sheets.

For about a year and a half during the war, an illness kept Baker confined to a Casablanca clinic. However, even there, she joined the women’s auxiliary of the Free French forces as a sublieutenant and performed for the allied troops.

For her work during the war, Baker was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur with the Rosette of the Résistance.

Civil Rights

When the war was over, Baker returned to France and turned her considerable energy to the fight for civil rights. She married (self-identified homosexual) bandleader Jo Bouillon, and though they eventually separated, they remained married throughout Baker’s life. Together, they adopted 12 children of different races and religions from around the world. Baker called them her “Rainbow Tribe.”

After 9 years of “retirement,” Baker found herself facing serious debts that forced her to return to performing. She returned to the stage with a musical autobiography called Paris mes Amours at the Olympia Theatre in Paris in 1959.

She often returned to the US throughout the 50s and 60s to support the Civil Rights Movement. While in the U.S., she refused to perform for segregated audiences, and in 1963, she was the only woman asked to speak at the March on Washington.

In 1969, she and her children were evicted from the chateau in southern France where they had lived since the end of the war. However, Princess Grace of Monaco stepped in, offering Baker and her family a villa in Monaco and helping to fund a new show titled Joséphine to celebrate the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut.

After a few performances of the new show, Baker died peacefully in her sleep in her chosen country, France. Even in death, Baker accomplished another notable first. She was the first and only American woman to be buried with military honors and a 21-gun salute in France. Over 20,000 people lined the streets of Paris to mourn her passing and honor her life.

References

- Josephine Baker Biography. (2020). A&E Television Networks. Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/performer/josephine-baker

- Josephine Baker. (2004). In Encyclopedia of World Biography (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 448-451). Detroit, MI: Gale. Retrieved from https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/CX3404700392/GVRL?u=txshracd2598&sid=GVRL&xid=c379cd99

- Norwood, A. R. (2017). “Josephine Baker.” National Women’s History Museum. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/josephine-baker

- Josephine Baker. (2003). Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved from http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/j/josephine-baker/

- Strong, L. Q. (2006). Baker, Josephine. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com. Retrieved from http://www.glbtqarchive.com/arts/baker_josephine_A.pdf

- CIA report on activities in Latin America of Negro singer Josephine Baker. (1953, February 10). United States: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved from https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/CK2349254187/GDCS?u=txshracd2598&sid=GDCS&xid=52ea60d3

- Josephine Baker in new challenge. (1969, March 11). Times, p. 5. Retrieved from https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/CS84504683/GDCS?u=txshracd2598&sid=GDCS&xid=8242988a

Resource Highlights

Videos

- von Wangenheim, A. (2015). Josephine Baker: Black Diva in a White Man’s World. San Francisco, California, USA: Kanopy Streaming.

- Nalpas, M. & Étiévant, H. (1927). Siren of the Tropics. Paris, France. [film]

- Allégret, M. & Nissotti, A. (1934). Zouzou. Paris, France. [film]

- Greville, E. T. & Nissotti, A. (1935). Princess Tam Tam. Paris, France. [film]

In her own words

- Baker, J. (1952). Speech in St. Louis on the Third of February, 1952: The Josephine Baker Home Coming Day. UMSL Black History Project.

- Baker, J., & Bouillon, J. (1977). Josephine. (1st ed.). Translated by Mariana Fitzpatrick. New York: Harper & Row.

- Baker, J., & Sauvage, M. (1931). Voyages et aventures de Josephine Baker. Paris: M. Seheur. (Ransom Center)

- Baker, J. & Sauvage, M. (1949). Les mémoires de Joséphine Baker. Paris: Corrêa. (Ransom Center)

Biographies

- Baker, J., & Chase, C. (1993). Josephine : the hungry heart (1st ed.). New York: Random House.

- Jules-Rosette, B. (2007). Josephine Baker in art and life : the icon and the image. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Print].

News & Magazine Articles

- La Baker Is Back. (1951). Life, 30(14), 55–60.

- Curtiss, T. (1959). JOSEPHINE BAKER CONQUERS PARIS ANEW. Variety (Archive: 1905-2000), 215(2), 1, 66. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1032388739/

Books

- Cheng, A. A., & Baker, J. (2010). Second Skin Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. Oxford : Oxford University Press. [electronic].

- McAuliffe, M. (2016). When Paris sizzled : the 1920s Paris of Hemingway, Chanel, Cocteau, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, and their friends. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. [electronic].

- Willis, D. (2010). Black Venus 2010: They called her Hottentot. Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press. [electronic].

Children’s Books

- Powell, P. H., & Robinson, C. (2014). Josephine : the Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. [Print].

Audio

- Baker, Josephine, Mario Braggiotti, and Jacques. Fray. “Josephine Baker : Complete Recorded Works, 1926-1927, in Chronological Order.” Document Records, 1999. Television.

- PARIS MES AMOURS / JOSEPHINE BAKER, avec l’orchestre dir : JO BOUILLON ; Orchestrations : JO BOYER. (1959). Retrieved from http://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8816212k