by Devon Murphy & Elizabeth Gerberich

Today thousands of students and educators nationwide are participating in GLSEN’s Day of Silence. Originally created by UVA student Maria Pulzetti in 1996 as part of a class project, GLSEN now helps organize the annual event in which participating students & educators remain silent throughout the school day to draw attention to erasure and harassment of LGBTQ students inside the classroom. Through their silence, participants intend to highlight the power of words—to show how both violent language and the failure to acknowledge existence contribute to the exclusion and dehumanization of queer and trans students.

Words are the foundation of our profession, and as library staff, it’s crucial we recognize the ways in which erasure and violence have been built—often purposefully—into our systems. Last month on the blog, Daniel Arbino & Gina Bastone highlighted how UT librarians subverted standard cataloging practices to create two collections, the Black Queer Studies Collection and the Latinx LGBTQ Collection, that challenge racist, homophobic, and transphobic library systems. In observation of Day of Silence, we wanted to both provide some further context for the cataloging practices that Daniel & Gina mention and spotlight efforts of queer and trans librarians in developing their own descriptive vocabularies.

Cataloging, by nature, requires categorization, and institutional classification of groups of people always reflects broader histories of power and struggle. Libraries, as institutions, are no exception. Epistemic networks connect library work to other academic, state, and professional institutions’ vocabularies, which inform the language we use in cataloging and descriptive practices today. Literary warrant, or the practice of using existing domain literature to create terms, directly links the descriptive methodologies used by varied institutions and scholars to thesauri like Library of Congress (LCSH) and the Getty Vocabularies. At LCSH, which was first formed in the 1890s, early to mid-20th century medical and psychological scholarship were employed as appropriate sources to build vocabularies for LGBTQ+ concepts, crystallizing terms meant to pathologize LGBTQ+ communities for organizing, describing, and disseminating library holdings. Other terms, like those for Indigenous gender identities, were deliberately excluded from these vocabularies in accordance with early anthropological theories and assimilationist government projects. LCSH’s dominance in cataloging standards broadened this impact with archives, academic institutions, and visual resource collections also implementing LCSH-derived content.

Legacies of biolence and exclusion are particularly salient in the lack of appropriate transgender, queer, and nonbinary terminology in LCSH that demonstrates the full & rich diversity of gender expressions. For example, nonbinary is still a “see also” term, meaning that it is not preferred for cataloging use and does not have a persistent identifier assigned, limiting its cataloging utility further. Problematic hierarchies and knowledge organization systems also hamstring LGBTQ+ descriptive efforts, as demonstrated by the fact that materials pertaining to Two-Spirit people are still located solely under the broader “Indians of America” subject heading. Issues abound in other vocabulary systems as well, such as the Getty Vocabularies: artist records within Getty’s Union List of Artist Names (ULAN) can only have a male, female, or N/A value for gender. While FAST, or Faceted Application of Subject Terminology, replicates some of LCSH’s terminology issues, due to its vocabulary base being built from LCSH terms.

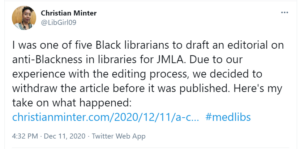

Wherever there are systems of power, there are always histories of resistance—changes to cataloging terms, like changes in any other institution, mirror these histories, too. Trans and queer communities have a strong tradition of self-determination: creating their own terms, vocabularies, and knowledge collectives to suit their needs, and LGBTQ+ library professionals have sought to change violent terminology for better & more inclusive knowledge sharing. In the 1970s and 80s, these efforts focused on changing terms in LCSH that classified gay and lesbian subjects as “sexual perversions,” and further sustained efforts in the following decades have led to additions of LGBTQ+ terms to reflect Trans identities, even though limited in scope. Adoption of terms like “Two-Spirit/2 spirit” and “Indigiqueer” in the catalog seek to reclaim Indigenous trans/queer identities violently suppressed by colonialism. Continuing in these traditions, library/archives staff and scholars have also collaborated to create resources outside of LCSH to improve LGBTQ+ description. Homosaurus is a linked data vocabulary for LGBTQ+ terms, meant to capture the linkages and complexities in LGBTQ+ identities. The Digital Transgender Archive includes rich collections on transgender history as well as a listing of transgender-related terms used throughout the world. And Histsex is a collaborative effort to create a bibliography of gender and sexuality terms and content.

It should go without saying that the language we use to describe and categorize people in library systems matters; providing all patrons with fair & open access to credible information is an unachievable goal when cataloging practices and search terms are violent, inaccurate, or exclusionary. And, at a point when the majority of state legislatures are considering transphobic and homophobic policy projects which draw upon the same descriptors as library standards, the persistent violence in cataloging systems is especially painful. On this Day of Silence, we invite you to explore the resources in this post & think about how you might use them in your work in the future.

Works Referenced:

Adler, Melissa A. “”Let’s Not Homosexualize the Library Stacks”: Liberating Gays in the Library Catalog.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 24, no. 3 (2015): 478-507. Accessed April 22, 2021.

Adler, Melissa. “Transcending Library Catalogs: A Comparative Study of Controlled Terms in Library of Congress Subject Headings and User-Generated Tags in LibraryThing for Transgender Books.” Journal of Web Librarianship 3, no. 4 (November 23, 2009): 309–31.

Drabinski, Emily. “Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 83, no. 2 (2013): 94–111.

Drescher, Jack. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences 5, no. 4 (December 4, 2015): 565–75.

Edge, Samuel J. “A Subject ‘Queer’-y: A Literature Review on Subject Access to LGBTIQ Materials.” The Serials Librarian 75, no. 1–4 (April 26, 2019): 81–90.

Eyler, A. Evan, and Saul Levin. “Interview with Saul Levin, MD, MPA, CEO/Medical Director of the American Psychiatric Association on the 40th Anniversary of the Decision to Remove Homosexuality from the DSM.” LGBT Health 1, no. 2 (March 13, 2014): 70–74.

Giami, Alain. “Between DSM and ICD: Paraphilias and the Transformation of Sexual Norms.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 44, no. 5 (July 1, 2015): 1127–38.

“GLBT Controlled Vocabularies and Classification Schemes.” Text. Round Tables, December 29, 2009. http://www.ala.org/rt/rrt/popularresources/vocab

Johnson, Matt. “Transgender Subject Access: History and Current Practice.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 48, no. 8 (September 27, 2010): 661–83.

Murphy, Devon. “Knowledge Organization Systems and Information Ethics for Visual Resources.” Visual Resources Association Bulletin 47, no. 2 (December 20, 2020). https://online.vraweb.org/index.php/vrab/article/view/193.

ONE Archives Foundation. “Uncovering the History of LGBTQ Archives and Libraries.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.onearchives.org/uncovering-history-lgbtq-archives-libraries/

Picq, Manuela L, Bosia, Michael J ; McEvoy, Sandra M ; Rahman, Momin “Decolonizing Indigenous Sexualities: Between Erasure and Resurgence” The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics (May 7, 2020)

University of Alberta Library. “Subject Guides: Equity, Diversity, & Inclusivity: Library Resources: Two-Spirit.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://guides.library.ualberta.ca/edi/2s

UT Libraries LGBTQ+ Resources:

- LGBTQA+ Studies LibGuide

- Black Queer Studies Collection

- Latinx LGBTQ Collection

- Queer Archives

- Transgender Studies Resources

![Rosie the Riveter poster with the phrase "We Can [edit]!" replacing "We Can Do It!"](https://hacklibschool.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/wecanedit.jpg)

In today’s

In today’s

The creative and entertainment industries are strengthened by the inclusion of non-white artists because they bring new stories to the screen and stage. Attempting to perform inclusivity by slotting non-white actors into traditionally white roles without any recognition of the changes this brings to a production is a way of silencing those stories and thus a form of racism.

The creative and entertainment industries are strengthened by the inclusion of non-white artists because they bring new stories to the screen and stage. Attempting to perform inclusivity by slotting non-white actors into traditionally white roles without any recognition of the changes this brings to a production is a way of silencing those stories and thus a form of racism.