Fisheries play a prominent role in the cultural identity, economy, and ecology of Oceania. Climate change and other man-made drivers of biodiversity loss are decimating the fisheries that Pacific Islanders rely upon for their subsistence and survival. In part one of this three-part blog series (see also: part two and part three), I dive into the significance of fisheries to Oceania as a key component of island life.

Tony Raymond, a reef fisherman from Vanuatu. Photo courtesy of Caritas.

Fisheries 101

Before we dive into an analysis of the importance of fisheries to Oceania, I think it is important to note a few aspects of what constitutes “fisheries” in this discussion.

Small-scale coastal fisheries and large-scale industrial fisheries

When talking about fisheries in Oceania, there are two primary types of fisheries active in the region: small-scale coastal fisheries and large-scale industrial fisheries. The FAO defines three categories of small-scale coastal fisheries: 1) small-scale commercial fishing, which supplies domestic markets and is the basis of fish export commodities, 2) subsistence fisheries, which provide the fish Pacific Islanders rely upon for nutrition, and 3) industrial-scale shrimp fisheries, which is not directly applicable to our discussion, as this fishery is limited to Papua New Guinea and outside this project’s definition of Oceania. As a whole, there are sparse available data on catch rates and the significance of coastal fisheries to both the region and the status of global fisheries as a whole.

Large-scale industrial fisheries in Oceania are dominated by extra-regional nations’ hunt for tuna in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of Pacific Island countries and territories. Nations such as China, Japan, Taiwan, the United States, and EU Member States including Spain and France are active in this region and dominate the commercial tuna fishery. Oceania is home to the largest tuna fishery on the planet, with over half of the world’s tuna stocks endemic to the region and accounting for approximately 60% of global tuna catch annually. Fishermen target four species of tuna – skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye, and South Pacific albacore – and use primarily purse-seine and longline techniques. Purse seine fishing boats acquire mainly skipjack tuna, becoming canned tuna at the end of the supply chain, while longline vessels focus on bigeye and yellowfin tuna to supply high-value sushi and sashimi markets in Southeast Asia.

Tuna are an essential part of the ecological and economic food webs in Oceania. Photo courtesy of GEF.

EEZs and International Waters

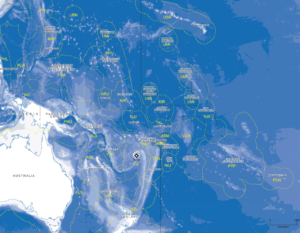

EEZs extend 200 nautical miles from each nation’s land boundary, making Oceania a unique region since nations with small land footprints, or that are scattered across myriad small islands, have substantial oceanic footprints. Pacific Island EEZs account for approximately 10 million square miles, or roughly 10% of the globe’s ocean surface and are visualized in the graphic below.

International waters fill the gaps between EEZs in Oceania. For highly migratory species such as tuna, that migrate seasonally and in response to changes in ocean currents and temperature, regulation amidst EEZs and international waters is a significant challenge.

The EEZs of Oceania. Photo courtesy of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

The Integral Role of Fisheries in Oceania

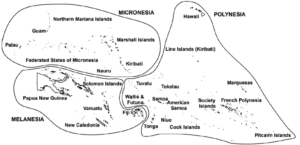

As with island geography, culture, and language, the nature of Pacific Islanders’ reliance upon fisheries is not uniform across the whole of Oceania. In the volcanic and resource-rich western islands of Melanesia (such as Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji, and Solomon Islands), fisheries are a less significant source of sustenance and economic opportunity when compared to the smaller islands of Polynesia (particularly Tuvalu and Tokelau) and Micronesia (such as Kiribati, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, and Nauru), whose inhabitants rely upon the sea for both sustenance and connection with other islands.

Regions of Oceania. Photo courtesy of Taylor and Kumar, 2016.

Fisheries play an essential role in the cultural identity of the Pacific Islanders who have called Oceania home for thousands of years. Islanders are the caretakers of the sea and are inextricably linked with the ocean, with fish and other marine species used in ceremonial traditions, to invoke spiritual connections with ancestors and their environment, to communicate value in exchanges between groups, and as part of the maritime fishing culture of the region. In Palau, although traditional methods of fishing are no longer employed as the primary method of fishing, Palauans continue to hold fishing in high esteem as a way to maintain their culture and customs. Individuals in American Samoa echoed this sentiment, with an interest in younger generations being capable with modern fishing techniques while maintaining their knowledge of traditional methods as a way of keeping their culture alive.

Aside from the cultural connection between the people of Oceania and their marine resources, the Pacific Ocean is a significant component of the region’s economy. Globally, more than 3 billion people depend upon the world’s oceans for nutrition, with seafood providing essential proteins and healthy fats for islanders’ diets, and employment in fisheries operations. Individuals who live along the world’s coasts eat nearly four times more seafood per capita than the global average. In Oceania, the highest reliance upon fish is in atoll countries like Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Federated States of Micronesia, with lower reliance on seafood in countries that have large inland populations, such as Vanuatu, or are more wealthy territories.

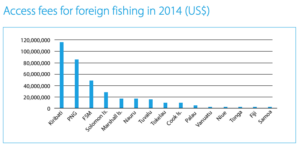

The region’s large EEZs provide an economic backbone for Oceania. Tuna fisheries generate approximately US$7 billion annually for the global economy and provide 10% of regional GDP. Countries sell access to the tuna resources within their EEZs to extra-regional countries as a key source of income for their economies. This is a particularly prominent source of income for Kiribati (constituting 42% of government revenue), Nauru (17% of revenue), and Tuvalu (11%).

Access fees to Oceania from foreign fishing. Photo courtesy of SPC.

Roughly 6-8% of regional wage employment stems from jobs relating to tuna fishing, in the offshore catch and onshore processing and canning industries. Onshore tuna processing is significant to the economies of American Samoa, Fiji, and Solomon Islands, with over 23,000 jobs created to date on these islands.

Fisheries are an Essential Piece of Life in Oceania

Pacific Island countries and territories are reliant upon the fisheries of their region, not only because of how they define themselves as people in relation to each other and the ocean, but for their very subsistence and livelihood. Climate change and other man-made drivers of biodiversity loss, such as overfishing and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, pose a serious threat to the people of this region.

In part two, I’ll describe the size of this threat and its impact on the islands and people of Oceania.