During the hockey World Championships in Stockholm and Helsinki in May 2013, the Swiss team won all seven group games, beat the Czech Republic and the United States in elimination games, but finally succumbed to Sweden in the final game in Stockholm on May 19. While the rest of the world barely took note, the Swiss public went absolutely nuts. The Swiss tabloid Blick even printed a free special issue—to celebrate second place.

Who won? Hint: not the Swiss team. (Blick.ch, accessed May 20, 2013)

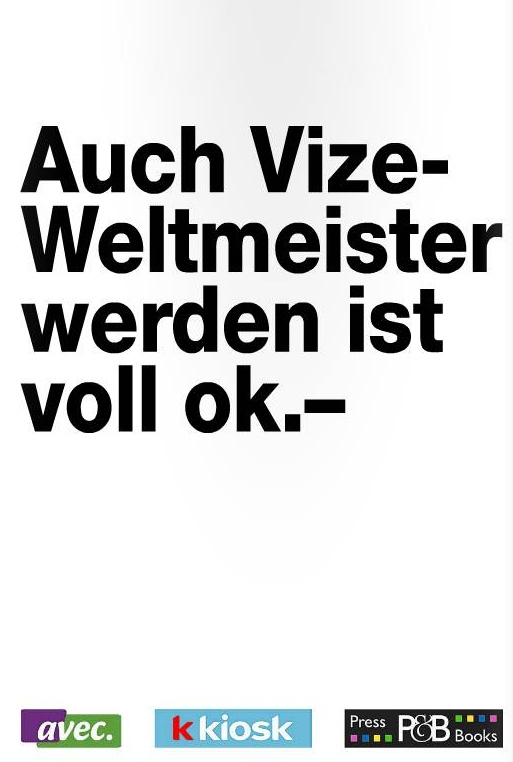

“Weltmeister der Herzen” (world champion of the hearts) was the big headline in gold letters on the cover of the 16-page edition. It also promises a “Poster unserer Helden” (poster of our heroes) as a centerfold. Even the more reserved Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the Swiss newspaper of record, wrote enthusiastically: “Die Schweizer schrieben in Stockholm Eishockey-Geschichte, ein Märchen vom unbeirrbaren Kampfgeist, von Einsatzbereitschaft und Selbstbewusstsein.” (The Swiss wrote hockey history in Stockholm, a fairy tale of unwavering fighting spirit, dedication and self-confidence.) Even international news outlets took note of the exuberant Swiss celebration of defeat, like the German cable news channel n-tv whose headline read “Schweiz feiert Silber wie Gold!” (Switzerland celebrates silver like gold!) The advertisement on the back cover of the Blick special free edition, sponsored by major Swiss newsstand operators, says it all: “Being vice world champion is totally okay, too.”

(Blick.ch, accessed May 20, 2013)

While in large countries, like the US, only victories count, expectations in small states are considerably lower, and Switzerland is a textbook example for this. The Swiss are happy if their team can keep up with the international competition. Losing is fine as long as the loss is not humiliating. Winning against teams from large countries is not expected, and when it does happen the Swiss fans are ecstatic. A good example is the victory against Spain in group play at the 2010 soccer World Cup. While losing the other two group games was disappointing, the Swiss team could return home with their pride intact. Just qualifying for and participating in a major tournament fills fans with pride. Being there was more important than winning, and having beaten the eventual world champion was just a bonus.

A notable example is the 2006 Soccer World Cup where the Swiss were eliminated by the Ukraine in a penalty shootout in the second round. The Swiss tabloid Blick wrote: “Our heroes have to go home. Without conceding a single goal. Yes, Switzerland even wrote a piece of World Cup history. They are the first team ever to have been eliminated from a World Cup tournament without conceding a single goal!” Being eliminated from the tournament in a penalty shoot-out without losing a game and without conceding a single goal during regular play was a moment worth celebrating: in defeat, the Swiss team just had set a new FIFA World Cup record. This is a fine example for how small states can tease out small victories out of what everybody else would see as a defeat. As winning the tournament was elusive, this small moral victory was worth celebrating.

In the recent hockey World Championship tournament, there were plenty of signs of victory in defeat as well. Victories against hockey powers like Canada, Sweden (in group play), the US, and the Czech Republic (twice) were celebrated in the media in enthusiastic headlines. Furthermore, two of the six players in the all-star team were Swiss, and the Swiss defender Roman Josi was chosen as the MVP of the entire tournament–both reasons for celebration. The message is clear: even though the Swiss team lost the big game, there is ample reason for happiness. As the tabloid Blick put it in its report on the game: “Ihr seid trotzdem Silberhelden” (You are are silver heroes nonetheless).

In the Swiss sportive world, defeat is acceptable as long as it is honorable. The sportive vocabulary is spiked with phrases that embody this spirit: terms like Achtungserfolg (respectable success [in defeat]) and ehrenvolle Niederlage (honorable defeat) are often used in the media to describe losses by Swiss teams or individuals. Wolfgang Bortlik evokes this attitude in his short 2008 monograph entitled Hopp Schwiiz! (Go Switzerland!) with the telling subtitle Fußball in der Schweiz oder die Kunst der ehrenvollen Niederlage (soccer in Switzerland or the art the honorable defeat). As sportive successes are not abundant in a small state like Switzerland, developing rhetorical categories to make failure look like success has become a national pastime.

(Blick.ch, accessed May 20, 2013)

This is how the Blick special edition could frame the performance of the Swiss national team as “Ein Märchen in 10 Akten” (a fairy tale in 10 acts), again using the fairy tale metaphor while completely glossing over the fact that the tenth act did not have a happy ending. Likewise, the ad by PostFinance on the opposite page congratulates the team and states that “all of Switzerland is happy about the World Championship success.” Even for the postal bank, second place is as good as winning.

Just playing in the final game in Stockholm thus ranks as one of the biggest successes in the history of Swiss team sports–the tabloid Blick ranked it second only to the victories of Alinghi in the America’s Cup in 2003 and 2007. The Alinghi victory in 2003 created an amazing surge of interest in sailing in land-locked Switzerland. If a Swiss individual or a Swiss team does well internationally–totally against all expectations, of course–interest in that sport rises dramatically. Before Martina Hingis and Roger Federer mesmerized the Swiss public with their Grand Slam victories, tennis was seen as an elitist, marginal sport with modest media attention. Now, the entire country watches when Federer plays in any tournament.

Before the final game in Stockholm, one question was discussed in the Swiss media over and over again: are we going to win? Can we win the big game? This question was also put to the players in the Swiss team. While they all answered in the affirmative, there always was a hint of doubt: if felt like the players did not really believe in the possibility of victory in spite of statements to the contrary. If you are from a small country, you know that you are not supposed to win big games. It felt like it was not the place for the Swiss to be on top of the hockey world. Being world champion in a major team sport is just unimaginable in Switzerland–it would have felt like a violation of the established order. The Swiss team had done enough to ensure a place in history and to make the Swiss proud. As winning could not really be imagined, it was okay to drop the big game. And they did.

A commentary in the Neue Luzerner Zeitung picks up this point and argues that the Swiss will never be world champions with this attitude. In their view, the Swiss now have two options. The first one is to indulge in total happiness over the best national team ever which celebrated the biggest success in Swiss hockey history.The commentary concludes, “If we do that, we will never be world champion.” The second option is to be proud of the Swiss performance, but not satisfied. When the new season begins in September, so the argument, the disappointment has to outweigh self-satisfaction–this is the only way to ever become world champion.

The Swedes did not have better players, they were not a technically better, and they were not better coached, according to this commentary in the Lucerne paper. The difference was one of attitude: the Swedes showed self-confidence to the point of arrogance: just as for the Swiss team winning was not in the realm of the imaginable, losing was not in the realm of the imaginable for the Swedes: losing in front of their own fans was not an option. They showed assertive body language, resolve in their actions, and a grim determination that signaled to the Swiss that they had no intention of losing this game.

This is a new kind kind of commentary and a new kind of language to talk about sports in Switzerland. We will see in the Olympic tournament in 2014 if and how fast the Swiss small-state-attitude towards winning can be adjusted.

One point of consolation: the Swiss success in Stockholm no doubt will have coattails. One result will be that a larger number of Swiss players will get the opportunity to play in the NHL–the undisputed top hockey league in the world. The Swiss media regularly report on the successes (and failures) of Swiss soccer, hockey, and basketball players who play in top leagues abroad. More Swiss players in the NHL means that there will be more feel-good-moments for the Swiss. So the Swiss will have more opportunity to be proud without making a real commitment to winning.