The other day, a petition from Campaign for America’s Future ended up in my in-box. Its subject line read: “Why is Walgreens Moving to Switzerland?” Of course, Walgreens is not moving to Switzerland. My Walgreens still will by around the corner from my house. And most corporate jobs will remain in Chicago. The first line of the e-mail reads: “Walgreens is an American success story. Or, at least, they used to be.” Wrong again: it still is, and will remain so even after Walgreens moves its corporate headquarters to Switzerland. It just will not pay taxes in the US anymore. But that, too, is very American. Ever since Ronald Reagan declared the government the enemy of the people, paying taxes no longer is a civic virtue. Avoiding taxation altogether is considered smart because the money would only serve to bloat the government.

The planned move by Walgreens was precipitated by its merger with Alliance Boots, a British drugstore chain. Alliance Boots moved its corporate headquarters to Zug, Switzerland, in 2008 which caused the very same discussion about corporate citizenship in Britain. Alliance Boots never had more than a mailbox in Zug. According to The Guardian, the move comes at a cost of £100 million to the British taxpayer every year. In 2013, the company headquarters were moved to Bern as Alliance Boots already had operations there. While Zug is the quintessential corporate tax haven, the move to Bern, which was missed by Bloomberg News, does little to change the story. A move to Switzerland by the Walgreen Corporation would have similar benefits. A few weeks ago, analysts from UBS, a global bank based in Switzerland, claimed that stocks in the Walgreen Corporation would rise 75 per cent if corporate headquarters were to be moved to Switzerland.

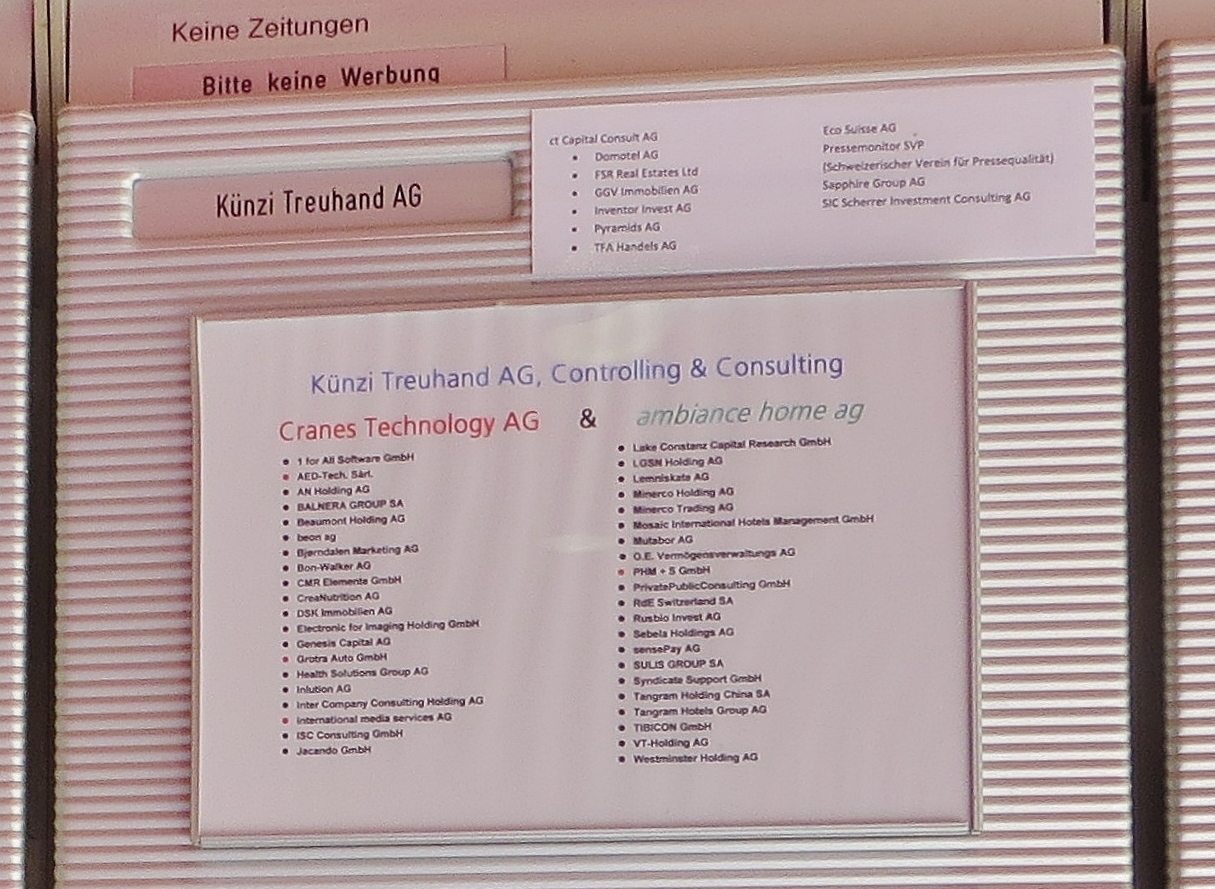

Modest multi-party office building at Baarerstrasse 94 in Zug. Alliance Boots was based here until 2013.

Clearly, Walgreens does not want you to read this. In 1904, Charles Walgreen traveled from his small-town home in Dixon, Illinois, to Chicago and opened a pharmacy and soda fountain. It is the quintessential American success story, but today’s corporation has little to do with its humble beginnings. Walgreens want you to believe that they are an American company that pays their taxes, that they are being a good corporate American citizen, and that they live up to their iconic status as a quintessential American corporation. In a wicked way, of course, they are: like so many other American corporations, they are moving their corporate headquarters offshore.

Large corporations are de-nationalized entities which nimbly navigate the global financial and fiscal system while maintaining the fiction of national citizenship for public consumption. Two years ago, Gregory D. Wasson, the chief executive of Walgreen Corporation, sought tax breaks from the state of Illinois the company is still based. At that point, he stated: “We are proud of our Illinois heritage. Just as our stores and pharmacies are health and daily living anchors for the communities we serve, we as a company are now recommitted to serving as an economic anchor for northeastern Illinois.” At the time Wasson made this statement, the merger with Alliance Boots was essentially a done deal.

Walgreens is not the first and probably not the last US corporation to move their headquarters overseas for tax reasons. But Walgreens is different in that it is part of daily life in the US. My Walgreens is not just a pharmacy, I go there as well when I am out of dish detergent or beer. When Transocean, the owner of the Deepwater Horizon platform which caused the huge oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, moved its corporate mailbox from Houston to Zug in 2008, nobody took notice. But Walgreens lives off he daily contact with American consumers, and in that it is seen as a quintessentially American brand that cannot be relocated so easily. And herein lies the chance to create public pressure not just to prevent Walgreens from moving to Switzlerland but to expose the fraudulent global scheme of corporate taxation.

So what does Campaign for America’s Future want you to do about this? They want you to send them ten bucks so they can “expose this scam, pressure Walgreens to do the right thing, and shut down the tax loophole that allows this to happen.” You can also sign their “Tell Walgreens: Don’t Desert America” petition. While I cannot argue against closing tax loopholes, this approach is merely cosmetic.

In 1998, the OECD published a report entitled Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue which arrives at the stunningly simple analysis: “Where activities are not in some way proportional to the investment undertaken or income generated, this may indicate a harmful tax practice.” Ultimately, the OECD had to abandon its efforts to develop non-abusive global taxation standards due to resistance from the wealthiest countries. The OECD report makes it clear that it is unethical for Swiss cantons (and other entities) to allow foreign corporations to incorporate and that it is harmful for tax jurisdictions where the actual economic activity of these corporations takes place. This practice particularly hurts developing countries, as Nicholas Shaxson argues in Treasure Islands (2012), that as a consequence become more dependent on foreign aid. Yet, fighting individual predatory jurisdictions, like many Swiss cantons, would only be marginally productive as corporations easily can move their mailbox to a different, equally beneficial jurisdiction.

One of the OECD recommendations was that a global standard should be established by which corporations should be taxed where their economic activity is taking place. We need to vigorously push for this standard, and we need to seek a fundamental change in how corporations are taxed globally. Corporations need to be taxed where they are producing goods and services and where they are using the infrastructure, not where they are having their corporate headquarters, i.e. their mailboxes. Such mailbox headquarters create a windfall for the host tax jurisdictions which in turn allows them to drop the corporate tax rates even more to attract even more corporate mailboxes. The Swiss canton of Zug is a textbook example for that.

The only real solution, ultimately, is to end tax competition between jurisdictions. In competitive tax environments, corporations win and taxpayers lose. Corporations and their lawyers always can move more nimbly than politicians and the polities they represent. Corporations can move their mailboxes as they please, pick where they pay taxes, and play tax jurisdictions against each other. Tax jurisdictions cannot move their citizens or their infrastructures. Unless we change the very system of how corporations are taxed, the Walgreens of this world will always have their way and citizens will lose out.

One of many mailboxes at Baarerstrasse 94 in Zug: Künzi Treuhand AG. About 50 corporations and business groups receive their mail here–meaning that this is where they are legally incorporated. One of their advertised specialties: helping foreign corporations set up and manage corporate headquarters here. This is big business, and there are many such companies in Zug.