Urban planning, political agendas, and history intersect in Delhi

By Aparna Rajeevan

Introduction

Delhi has a history dating back to 1000 BCE, serving as capital for two major empires: the Mughals and the Delhi Sultanate. The long history of Delhi has inscribed seven layers to the city, providing it with a rich socio-cultural heritage. In 1931, Delhi was chosen as the capital for the New India and still reflects a history of struggle, power and freedom.

In the 1920s, the city plan for New Delhi developed by Edwin Lutyens tried to symbolically connect important landmarks and nodes through road axes and visual corridors. Lutyens’ design sought to showcase Delhi’s political history starting from the medieval period while marking the transition to colonial governance by designing the official buildings in the Indo-Saracenic style. The Indo-Saracenic architecture which emerged in the 19th Century embodies the synthesis of Indian, Islamic, and Western architectural styles like the Neo-Classical, Gothic, and the Victorian.

The area encompassing Rashtrapati Bhavan, India Gate, and the axis along Rajpath is now undergoing a redevelopment process known as the Central Vista Project. Led by the government of India, the project is highly controversial because it seeks to erase the visual corridors that connect different religious landmarks and buildings of high significance. Although the project was challenged in court for the lack of transparency in the redevelopment planning process, the Indian Supreme Court sided with the government despite the traditional judicial protection afforded to civic participation. As a result, the project is erasing the history of communities located in this area, ignoring citizens’ attachment to place and converting public open spaces for exclusive use by the government.

Analysis

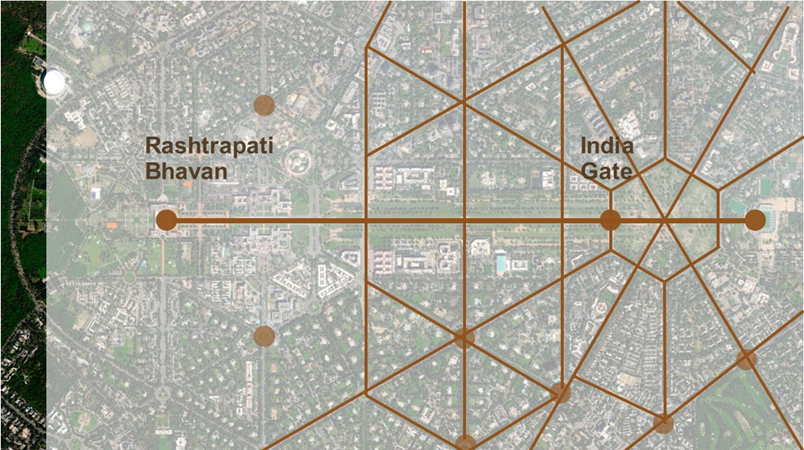

Delhi’s master planning followed a strict geometry with radiating roads and vistas. One of the prominent features were the road axes connecting the important civic buildings with the significant buildings of the previous regime. One particularly important axis is the Rajpath, which connects the Rashtrapati Bhavan with India Gate, a war memorial. Known as the power corridor of Delhi, most of the important buildings of Delhi, including the Parliament House and Secretariat Buildings, are situated along this axis.

A secondary axis connects the Rajpath to the Juma Masjid which is regarded as a principal symbol of Islamic power in India and is closely identified with the ethos of Old Delhi. This axis isn’t a direct road but rather a symbolic alignment of Delhi’s historic and cultural significance. It links Old Delhi, the heart of the Mughal Empire, with New Delhi, the seat of British and later independent Indian governance.

The two landmarks, Juma Masjid and the ceremonial Rajpath, reflect the layered history of Delhi, transitioning from Mughal dominance to British imperialism, and then to the Republic of India.

However, in 2005, Akshardham temple was built along the banks of the Yamuna River. A new axis connecting the new temple with the Rajpath reflects changing priorities in the city’s symbolic geography, potentially altering earlier narratives and connections. This new connection emphasizes Hindu cultural identity, moving away from the Mughal-British architectural narrative. At the same time, the Central Vista redevelopment further challenges the existing urban form premised on connection, proposing a more centralized and isolated governmental enclave.

The area undergoing development currently has a lot of green spaces which are accessible to the public. However, the Central Vista Project has designated this area as a governmental enclave, which will significantly reduce the amount of open green spaces available. The project also aims at demolishing important historical buildings to accommodate new structures. Some opposition leaders have called for protection of all historical sites in the area, pushing for open dialogue to address these issues. Heritage and conservation groups have expressed concern over how the project might impact the historic landscape of the area, which holds significant cultural and architectural value. There have also been several community-led initiatives calling for heritage conservation and public engagement. Many community members and groups have filed Public Interest Litigations (PILs) and petitions to challenge aspects of the Central Vista Project in court. These petitions often call for greater transparency, urging the government to prioritize careful handling of historical sites. Some petitions have also sought to halt construction until further consultations are carried out.

Implications

From the perspective of Bayat & Biekart (2009), the Central Vista Project can be understood as the result of a neo-liberal planning agenda that prioritizes national image-making, economic competitiveness, and centralized power over the needs of local communities. As Siame (2017) explains, modernist approaches to planning were seen as a way to bring progress and modernization to cities in the Global South. However, they have often failed because they disregard local realities, socio-cultural contexts, and inequalities, and exclude the voices of these communities in the decision-making process.

Because neoliberal urban policies blend market-driven motives with seemingly progressive ideas like decentralization and participation, they often undermine true urban citizenship (Bayat & Biekart, 2009). The “right to the city” remains contested, as minority residents struggle against exclusion and inequality.

Furthermore, the Central Vista Project will potentially disrupt the longstanding spatial relationships that helped Delhi shape its urban identity. The removal of these corridors and landmarks raises important questions: How do these changes affect the collective memory of the city? What is the emotional and psychological impact on communities who feel their histories are being erased? Friedmann (2010) explains how the history and culture of a place shape the way people experience it. The cultural and historical aspects of a place give it significance. If urban planners design spaces without considering the cultural and historical context, they risk stripping away the original essence of these places. This approach focuses solely on modern developments, attempting to erase the rich history and identity that make the place meaningful to its inhabitants.

Lutyens’ Delhi: Spatial layout highlighting radial patterns, grand vistas and axial symmetry. Source: Author Generated.

Rajpath (central ceremonial boulevard) and India Gate, Delhi. Source: https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-1105487121-delhi-aerial-view-capital-city-india-iconic

The new parliament besides the old one. Source: https://constitutionsimplified.in/blog-post486

The new and old symbolic axes. Source: Author Generated.