By Caroline Daigle

Introduction

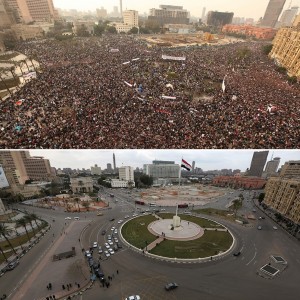

On January 25, 2011, after 30 years of oppression at the hand of Hosni Mubarak’s regime, protestors took to the streets of Cairo and initiated the 18 day Egyptian Revolution. At the epicenter of this revolution, both literally and figuratively, lay Cairo’s famous Tahrir Square. After an initial mass protest in the square on January 25 followed by police retaliation and brutality against protesters on January 26, the square was finally occupied by “the people” and it existed as a city of nearly 400,000 until Mubarak resigned, ending his three decades of authoritarian rule at the collective demand of a mobilized citizenry. Tahrir means liberation, and I argue that it was because of the square’s agency and the people’s infrastructure that liberation became possible.

The materiality of Tahrir Square and the agency of non-human actors involved in the revolution played critical and active roles in the revolution. Likewise, the human network that emerged as “the people” during the revolution represents a crucial infrastructure that facilitated collective protest. Thus, this case is exemplary of insurgent planning in its overt expression of these often-unrecognized phenomena: non-human actors with agency and human networks that form the building blocks for infrastructure. By overcoming the traditional divide between human and non-human actors and asserting new roles for the use of public space, the 18 days of Tahrir exemplify how radical notions of planning can be used to understand and catalyze mass social change.

Analysis

Analyzing the events of Tahrir Square through a lens of assemblage theory facilitates a new understanding of the “place” involved in the Egyptian revolution. Pablo Sendra uses assemblage theory to locate Sennet’s 1970 notion of “the uses of disorder” within urban planning praxis (Sendra 2015, 821). He argues that the convergence of humans and non-human actors such as architecture, place, regulations, and histories allows for a certain “disorder” and the “unplanned use of public space” to emerge, exercising a powerful agency in the city (Sendra 2015, 822).

From this perspective, we can better understand how Tahrir Square’s physicality played a crucial role in catalyzing revolution. It is centrally located in Cairo with a multitude of arterial roads feeding into it from across the city. The square has historically been associated with public gatherings as well as with matters of the State, but under Mubarak, the spirit of Tahrir Square was stifled. Neoliberal policies began to redefine the public space as privatization and gentrification took effect and made it largely inaccessible. The authoritarian regime also erected barriers to physically segment open space in the Square in order to stifle mass gatherings and criminalize congregation (Elshahed 2011). Nevertheless, during the revolution the people set up camps within the space, devising their own versions of land use regulation by actively disobeying the regime’s order. Destroyed police vehicles formed a barricade around the new “city” of Tahrir, making the invented space of revolution formally demarcated by materiality that represented the toppled regime (Shokr 2011). Thus, in spite of and against the state’s imposed order, the people came together to creatively assemble a new conceptualization of urban space.

In coming together within this space, “the people” also became “a platform for reproducing life in the city” (Simone 2004, 408). The potent force behind Tahrir Square’s occupation can be better understood by analyzing the heterogeneous citizenry that promulgated it. The masses in Tahrir Square can be considered an embodiment of Simone’s concept of “people as infrastructure,” which is defined as “flexible, mobile, and provisional intersections of residents that operate without clearly delineated notions of how the city is to be inhabited and used” (Simone 2004, 407.) The revolution was framed by a simple demand written across a banner that hung over the square: “The People Want to Topple the Regime.” This collective identity of “the people” reached across religion, politics, class, age, and gender in order to forge a new network and further an “impossible demand” (Zizek quoted in Kamel [2012, 39]). In the expression of flexible citizenry within Tahrir Square, a notion of “the people” exists despite particular identities (Elshahed 2011, Kamel 2012, Shahin 2012). Within Tahrir Square, a bounded place was “…linked to specific identities, functions, lifestyles, and properties [where] the spaces of the city become legible for specific people at given places and times. These diagrams — what Henri Lefebvre calls “representations of space”—act to “pin down” inseparable connections between places, people, actions, and things” (Simone 2004, 409). Even though “the people” protested the regime for different reasons, the collective voice of these protests forged an infrastructure of inseparable connections in the assembled space within Tahrir Square, propelling social change in a tangible way.

Implications

Per Miraftab’s (2009, 33) definition of insurgent planning practices, both the human and non-human components of the “city” developed in Tahrir Square are “counter-hegemonic, transgressive and imaginative” as they seek to disrupt the order of urban life in pursuit of a radical alternative. First, they are counter-hegemonic in their direct rejection of the state’s authority, disregarding laws against mobilization and demanding the downfall of the regime. Second, they are transgressive in how they catalyzed the Arab Spring and tapped into a collective memory of 30 years under authoritarian rule in order to seek liberation from within Liberation Square. Finally, they are imaginative because they created a utopia within the space that the State had turned into a neoliberal dystopia (Kamel, 2012).

This case encourages us to rethink the nature of planning. By applying assemblage theory, we can better understand the role of physical space and non-human actors in catalyzing mobilization and disorder. Similarly, understanding “people as infrastructure” (Simone 2004) reveals how heterogeneous networks of actors can form a collective voice for large-scale change through collaboration across individual identities. Tahrir Square ultimately makes us realize the simultaneously “place-less” and situated nature of community. The square provided the necessary, bounded, and situated “place” for revolution, but “the people,” a critical infrastructure, is an inherently (and necessarily) placeless and fluid community. The intersection of these two actors—a placeless community in a specifically bounded space—proved to be a powerful force that spurred social mobilization in the city. It is in these spaces where revolutionary change can be born.