Zapatista Caracoles provides space for insurgency and new planning pedagogies

By Alyson Vargas

Introduction

The Zapatista movement located in Chiapas, Mexico, demonstrates that alternatives to western rationalities of planning and development can serve as a foundation for new planning pedagogies. The Zapatista movement has persisted by performing continuous acts of resistance, as they demand Indigenous autonomy. The movement, which exemplifies the ongoing struggle against imperialism and neoliberalism by empowering and giving agency to communities and their members, has sparked international dialogue and solidarity.

The state’s mistreatment of Indigenous people, false offers of dialogue and unresponsiveness to the challenges facing the Indigenous communities in Chiapas have inspired the Zapatistas’ internal organization for self-governance. The community administration is built on units of governance known as “Caracoles,” which function as centers for political, cultural, and general communication exchanges for Zapatista communities as well as national and international actors. Self-governance in the Zapatista territories and local municipalities is structured through the framework of “Mandar Obedeciendo,” which is used as a consensus tool for planning while fostering insurgent citizenship and insurgent planners. Through participatory planning processes framed by Mandar Obedeciendo, community members take ownership of their institutions, initiating and implementing local programs and projects.

Analysis

This village-based organizing process is the foundation for the Zapatista movement’s success in reclaiming spatial territories and using these spaces to redefine their power. The Caracoles can be thought of as a basis for insurgent planning as they serve to “construct new social imaginaries of the production of human settlements and of the state” (Putri, 2020: 1847). The Zapatistas view these new social imaginaries as an alternative globalization movement that does not repeat the vertical model of top-down decision-making and does not have a central demand. The Zapatista movement is careful to respect local differences and forms of decision-making through their focus on Indigenous ontologies, which calls for viewing resistance as a way of persisting in the face of neoliberalism. The Zapatistas thus broaden our understanding of insurgent planning by expanding definitions of citizenship based on the right to exist, while creating new forms of insurgent planning pedagogies based on community imaginaries and decision-making (Putri, 2020).

But the Zapatista territories are still contested and challenged by national and global institutions. Since “there is no definable regional territory to rule over” (Amin, 2017: 36), the movement faces limitations to their power within the region. Historically, the movement has focused on physical expansion in order to reject neoliberalism and globalization, for example by establishing new caracoles. However, the movement is subject to rhetoric from outside actors that seeks to undermine the movement’s legitimacy and its attempts to gain autonomy. In response to these challenges to their legitimacy, the Zapatistas have established Good Government Boards to ensure that the government is serving the people and provides oversight power to residents in order to minimize the distrust stemming from previous undemocratic acts by the government (no matter who was in office.) These Boards also provide spaces for critical reflection of institutional relations of power, revealing the fear tactics of institutions that challenge Zapatista self-governance. At the same time, the Boards serves to maintain Indigenous autonomy by identifying “efforts to address the state–society relationship from which oppressive systems emerge” (Putri, 2020: 1860).

The Zapatistas’ decolonial efforts to strengthen cultural identities have succeeded by taking advantage of moments of insurgency to create spaces of autonomy and free determination. To help institutionalize liberating practices, spaces of dissensus were created through the Caracoles in opposition to undemocratic neoliberal development regimes. This dissensus provides the Zapatista movement with sufficient fluidity to adapt, expand, and grow in opposition to “Western Knowledge rooted in modernity” (Gudynas 2011: 443) while pursuing development strategies based on community needs. The collective development of forms of communication within the communities makes it possible to protect its members, making their forms of self-governance and citizenship ideas that are “continually being created” (Gudynas, 2011: 443). The caracoles are “places being changed or adapted as people become empowered through resistance” (Sharp et al, 2000, as cited in Young, 2001: 609).

Implications

The Zapatista movement emphasizes that the government they have created, the territories they reclaim, and the physical and social structures that they build are unique to the Zapatistas. That is to say, their community-based collaborative planning model is suitable for participatory governance within their community rather than a blanket solution for other Indigenous people in Mexico, let alone the world.

To construct alternatives to development that are both long-lasting and plausible, Gudyanas (2011) calls for pursuing decolonial alternatives emerging from Indigenous communities that have been impacted by neoliberal projects and development. Drawing on Gudynas’s conceptions, the Zapatista governance structure can be considered an alternative to western development models. The Zapatistas incorporate Indigenous ontologies into their everyday planning and organizational practices in order to challenge development approaches that will primarily benefit outside actors. The value placed on indigenous knowledge strengthens the movement and helps maintain their alternative model. Additionally, indigenous knowledge further serves to untangle and rewrite the universalized dualisms stemming from the knowledge systems of the West (Escobar, 1996).

Their consensus-based and collective form of self-governance has allowed the Zapatistas to develop culturally, socially, and economically. The Zapatistas’ anti-imperialist work to “seek and build inclusive spaces” (EZLN Communique, 2001) supports the interests of Indigenous people rather than preserving the power of the national government. Through these community-based models, resistance persists through the collective as they continue to survive the ongoing colonization and neoliberalism in modern Mexico. The Zapatista movement has shown that consensus building does not have to follow western rationalities (Watson, 2007), as the Zapatistas are informed by necessity and survival through acts of informality (Watson, 2007: 2269) based on Indigenous ontologies and practices of self-governance.

Ultimately, the Zapatista movement is a model of self-governance that utilizes bottom-up development to achieve initiatives that benefit the community and its members located within their informal space (Numbogo et al., 2018). The Zapatistas’ work to identify and collectively address their problems and challenges is an inspiration for others in search of alternative models that are unique to their social, cultural, and spatial geography. Further, the successful organization of the Zapatistas community compels planners to use their formal tools with humility as facilitators within these community-driven spaces, as they navigate outside authorized channels to create new forms of citizenship (Numbogo et al., 2018). Lastly, it is critical to recognize international acts of solidarity that have supported Zapatista territories as invented spaces (Miraftab, 2009) for information sharing. It is in these technical spheres (Putri, 2020) where the new planning pedagogies of the Zapatistas have grown and spread.

Source: San Andrés Accords dialogue between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican Government.

Source: You are in a Zapatista Territory. Here the Community rules, and the Government Obeys. Good Government Board. Central Heart of the Zapatistas in front of the World. High Zones.

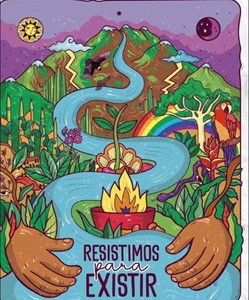

We Resist to Exist. Source.

Source: Waging Nonviolence | 3 April 2018