Informal Settlement Fights for the Right to Stay amid Flood Risk in Asunción, Paraguay

By Anita Machiavello

Introduction

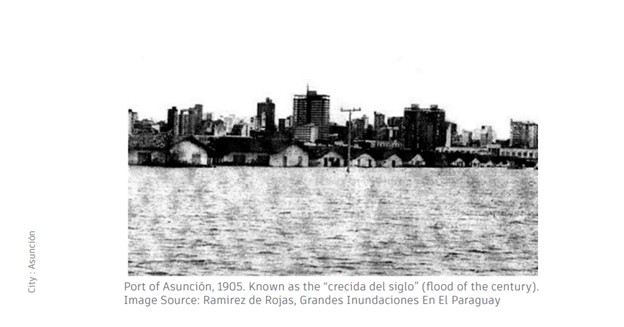

Bañado Sur, one of Asunción’s largest informal settlements, has endured decades of cyclical flooding and state neglect. Located along the floodplain of the Paraguay River, Bañado Sur is home to thousands of families who make a living through recycling, domestic labor, and other informal jobs. Every rainy season, rising waters force people to leave their homes and stay in temporary shelters until the river goes back down. These cycles have made the community physically vulnerable but also led to tight social networks, survival routines, and practices of mutual aid that sustain daily life and support collective resistance to relocation (Zibechi, 2008).

In recent years, Bañado Sur has become the focus of major redevelopment initiatives, most notably the Bañado Sur/Tacumbú Housing and Rehabilitation Program linked to the Costañera Sur waterfront megaproject, financed in part by the Inter-American Development Bank. While these projects are sold as efforts to improve resilience and modernize the area, they often lead to temporary or permanent displacement (Hicks, n.d.). In response, grassroots organizing in Bañado Sur has advanced what Miraftab (2009) calls insurgent planning, where marginalized residents engage in collective action outside state-sanctioned ‘invited spaces’ to assert their own planning visions. COBAÑADOS, the General Coordination of Social and Community Organizations of the Bañados, has been central to resisting displacement, facilitating community mobilization, and producing counter-narratives to official planning proposals.

Analysis

The planning dynamics in Bañado Sur are shaped by what Watson (2003) describes as ‘conflicting rationalities.’ For state institutions, the floodplain is understood through a technocratic “impulse” (Kamete 2013) that emphasizes hazard mitigation, land clearance, and the expansion of urban infrastructure, thus reproducing colonial hierarchies of expertise (Siame et al. 2025). The state’s approach in Bañado Sur aligns not only with regional redevelopment agendas but also with broader global trends in which dominant planning rationalities legitimize dispossession while obscuring community-based alternatives.

Roy’s (2005) framework of urban informality further illuminates the uneven regulatory environment in which Bañado Sur exists. Roy (2005) conceptualizes informality not merely as a condition of the poor but as a “system of exception” through which the state selectively applies or suspends regulations to advance its own interests. In the context of Bañado Sur, this logic of exception becomes evident as the state tolerates informality for decades yet invokes its illegality when the land becomes desirable for large-scale redevelopment. The power to toggle between tolerance and enforcement enables planners to justify displacement as a technical necessity, even though the precariousness of residents’ tenure is itself a product of the state’s long-standing, selective inaction.

Residents, however, operate with a different set of rationalities rooted in place-based identity, long-standing neighborhood patterns, informal jobs, and community-led efforts. Their attachments to Bañado Sur reflect what Holston (2008) terms insurgent citizenship, whereby marginalized groups generate knowledge and articulate decolonial planning imaginaries that challenge dominant logics of modernization (Siame et al. 2025). During major floods, neighborhood commissions (also known as comisiones vecinales) coordinate evacuations, share food, organize temporary shelters, and document damages. Led by COBAÑADOS, residents have carried out countermapping initiatives to contest official redevelopment plans and claim visibility (Zibechi, 2008), producing their own spatial data on household locations, community facilities, and flood impacts to demonstrate the feasibility of onsite upgrades (Benítez & Frutos, 2019). These efforts are complemented by women-led organizing, especially through ollas populares and care networks that mobilize resources, maintain social cohesion, and assert forms of collective governance during crises.

These mobilizations show how insurgent planning emerges through multiple modes of organizing, including relational, place-based, and performative strategies that challenge dominant planning logics (Luckett 2020). The organizing in Bañado Sur reflects intertwined forms of action: residents mobilize through neighborhood commissions, cultural events, and public demonstrations, all of which operate as insurgent practices that contest state narratives and assert alternative urban futures. Together, these forms of grassroots action demonstrate that Bañado Sur’s political agency is not episodic but embedded in longstanding organizational infrastructures that challenge top-down redevelopment and assert a right to remain.

Implications

This disconnect between formal planning and community knowledge underscores broader implications for international planning theory and practice. First, the case highlights the limitations of technocratic and neoliberal planning rationalities that assume displacement is an acceptable tradeoff for risk reduction. By prioritizing flood management goals and urban redevelopment over social continuity, such approaches reinforce historical patterns of exclusion in Latin American cities. Second, the case demonstrates the necessity of recognizing multiple epistemologies of risk. Residents of Bañado Sur have long adapted to seasonal flooding, developing social and infrastructural practices that are ignored when planners rely solely on engineering models. Acknowledging these forms of knowledge is critical to designing interventions that do not reproduce harm. Lastly, the case underscores the importance of decolonial planning approaches that decenter state expertise and disrupt the coloniality embedded in urban transformation projects. As Siame et al. (2025) argue, narratives emerging from marginalized communities expose the partiality of dominant planning norms and reveal alternative pathways rooted in justice, dignity, and community-defined priorities. In Bañado Sur, these narratives foreground not only the right to stay but also the right to co-produce the city.

Source: The Santa Ana neighborhood in Bañado Sur during one of the floods.

Source: McIntosh, A. A. (2022). Inhabiting wetness (Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Source: The northern and southern wetlands are the most affected by the rising Paraguay River. | Photo: Daniel Riveros.