Life in Korea’s newest new city

By Jongmoon Lee

Introduction

Following the Korean War, Korea chose to pursue large-scale development of new cities with high-density apartment-oriented housing as the most effective way to develop areas devastated in the war. These new cities are developed under the Special Act (“Special Act on the Construction and Support of Innovative City Acceptance of Public Institutes Relocating to Local Cities”), which was implemented in 2009 to develop innovative cities that would foster national development and improve national competitiveness. Such cities would allow public institutions to be relocated from the Seoul Metropolitan Area to aid in the regional development of the country. The concept of “the innovative city” is premised on close relationships between industries, universities, research institutions, and public institutions, and calls for a residential environment that includes housing but also provides opportunities for housing, education, and culture.

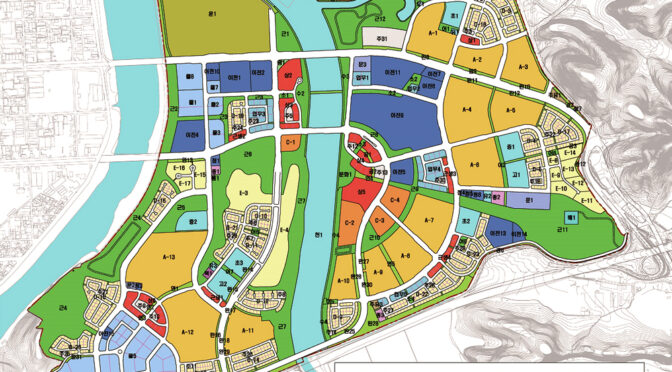

Like other new cities in Korea, Jinju Innovative City in South Gyeongsang Province is a high-density, compact, and walkable city. All the buildings have a modern look with clean exteriors and careful landscaping, including street trees, parks, and pedestrian and bicycle paths, allowing residents safe and easy access to their homes, commercial facilities, and workplaces. The city hosts a number of public institutions, including Korea Land and Housing Corporation, Small and Medium Business Corporation, and Korea Facility Safety Corporation. One of these public institutions, the Korea Land and Housing Corporation, is a state-run company that developed the entire new city, and its headquarters in the Seongnam metropolitan area was relocated to Jinju Innovative City in 2015.

However, the new city was built in the vicinity of the old city of Jinju, and the contrast between the two is stark. Unlike the Innovative City, the old city is composed of old and low buildings and lacks pedestrian and bicycle paths, making it difficult to ride a bicycle and uncomfortable for the disabled to move around. There are few street trees providing shade in the hot summer. While power lines are buried underground in the new city, in the old city they are all located above ground, making for a more unsafe and less pleasing streetscape.

Analysis

The National Land Planning and Utilization Act calls for a public hearing for existing residents when new cities are to be developed. In general, the public hearing is conducted in the city hall, with officials explaining the purpose of the project and the land use plan, and answering questions from the audience. However, these meetings are typically only attended by investors and others with economic interests in the area, and low-income residents in the area are not fully informed about the negative implications of such new city. This dominance of private sector interests has been reported elsewhere (e.g. Koch, 2015, in the case of Barranquilla, Colombia), resulting in land-use plans and projects that primarily respond to the priorities of land-owning companies and the construction sector (Koch, 2015: 407).

The development of Jinju Innovative City caused harm to low-income residents who were already living in the area. Housing prices began to rise as elite middle-class families moved there from the Seoul metropolitan area, attracted by the more comfortable residential environment. While new residents came to enjoy significant social and political advantages, the old city center began to empty as businesses moved into the new city. The influx of wealthier residents led to a polarized city, with low-income residents suffering from high prices and worsening living conditions.

This polarization was a result of building the new city according to western models without critically considering their applicability for the region. Western urban models originally emphasized the development of functional and production-oriented cities to contend with increasing industrialization. However, as Watson (2009) points out, the current situation in the Global South is different from the Western context when these predominant planning paradigms emerged. “In many cases, these inherited planning systems and approaches have remained unchanged over a long period of time, even though the context in which they operate has changed significantly” (Watson, 2009: 2260).

Kamete suggests that this uncritical acceptance of Western models is due to an obsession with modernity. Through the colonial period, local authorities believed that the colonial masters’ model was superior, leading to a heritage of top-down planning that is harmful to marginalized populations (Kamete, 2013b). In the case of Jinju, such planning persists in part because the middle class supports the new designs as more convenient and reflective of their class status, as Mehta (2016) found in Ahmedabad, India. Mehta explained that there is a strategic nexus between the middle class and neoliberal politics, with mega-development projects providing an opportunity for the middle class to reproduce their class status (Mehta, 2016).

Implications

While the new cities are functionally sound with high densities and walkable environments, the lives of low-income residents are sometimes negatively impacted. The time has come for Korean society to think deeply about what kind of cities to build and how to build them, and to take into consideration not only the new residents but also vulnerable groups already living in these areas. Insurgent planning approaches (Miraftab, 2009) would allow for more active participation by socially disadvantaged residents in the development of new cities. As Holston and Caldeira (2014) suggested, even if citizen participation is institutionalized, the rich will benefit the most, making it necessary for working-class people to engage in insurgent planning.

South Korea has historically experienced many challenges, including the Korean War and Japanese occupation. This historical fact has brought pressure on Koreans to develop national competitiveness in a short period of time. Also, before democratization, criticism for state-led policy projects was near impossible. Because of this history, the majority of Koreans have blindly supported Western development models, and few have thought seriously about the lives of vulnerable people who may be harmed by such models. One way to change this is to pursue a ‘decolonization of the mind,’ as suggested by Miraftab (2009). The unconscious sense of the “inferiority of the colonized and the superiority of the colonizer” (Fanon, 1986: 1967) blocks the liberation of the colonies and makes them keep following the western model. Instead, Korea should pursue forms of planning and urban development built on Korean characteristics and values.

To achieve this, we must historicize the planning process associated with the development of new cities, recognizing that Western urban models have been deployed historically through colonialism, Apartheid, and more recently through neoliberalism. So far, little research has been conducted on the impact of new city development on communities already located in the surrounding areas, suggesting that scholars, community groups, and government officials should work together to better understand the adverse effects of new city development and thus develop a uniquely Korean planning approach.