Informal Markets’ Role in Territorial Struggles and Queer Placemaking

By Sergio Morales

Introduction

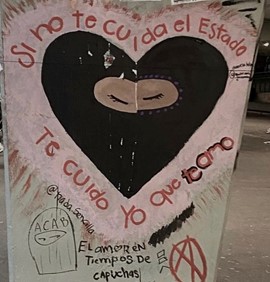

Between the crossings of the two most important avenues in the center of Mexico City lies La Glorieta de los Insurgentes, a public space which the local LGBTQ+ youth has appropriated and made their home via an informal market called La Tianguis Disidente (Barraza, 2022). Colloquially known as La Tianguis, the market is a “protest in response to the economic violence exercised against LGBTQ+ bodies” (La Tianguis Disidente, 2022). It is solely composed of queer, transgender, and gender-nonconforming (QTGNC) vendors from low-income peripheral neighborhoods in eastern Mexico City, many of whom do not have selling permits nor are required to pay floor fees. Besides offering free HIV and syphilis testing, La Tianguis also hosts marches, drag shows, hip-hop dance lessons, live music, vogue dance workshops, and art retreats to foster community. The space is also known for its radical political graffiti, with messages such as “Long live the dissidence against heteronormativity” and “If the state doesn’t take care of you, I will take care of you because I love you” plastered in all corners. While informal markets are at the heart of Mexican cultural expression and insurgency, La Tianguis has amplified the struggles of low-income QTGNC people amidst cisheteronormativity and neoliberal capitalism.

Analysis

While Kinyanjui (2014) describes informality as “a refuge or safe haven for victims of neoliberalism” in the economic sense, La Tianguis demonstrates that informality can also provide a social and physical safe space for LGBTQ+ youth. According to vendors in the market, getting a job in Mexico as a queer person of color is difficult because of applicant discrimination as well as government documents not coinciding with one’s identity (Hernández 2021, Luchadoras MX 2021). For trans people, who are the most affected by discrimination and thus rely on jobs like hairdressing and sex work, a vending stall in La Tianguis provides a critical additional source of income (Aquino, 2021). In particular, for youth rejected by their families, the market serves as a space to generate money to afford gender-affirming treatment and clothing and provides a refuge against violent homophobia and transphobia. For example, if outsiders harass vendors, the vendors can shout “¡fuego!” to alert everyone in the market for help.

While certain local movements across Mexico use informal markets as tools to reclaim spaces in city centers, the greater informal economy can still be exclusionary due to the prevalence of patriarchal attitudes. Although informal markets led by women called mercaditas emerged in response to the economic violence exerted by neoliberal capitalism and patriarchy, these tend to be exclusively for women vendors and sometimes exclude certain QTGNC identities (Aquino, 2021). Thus, the dynamics between La Tianguis and the greater informal economy illustrate Livermon’s (2013) concept of usable space, as queer people can rework and navigate heteronormative spaces via appropriation. Appropriation in this scenario implies not only claiming space in white gentrified city centers but also the appropriation of space in a local heteronormative informal economy.

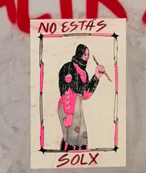

Similar to how queer youth in Vasudevan’s (2022) article appropriate spaces to create an imagined volleyball court to securely explore and perform their QTGNC identities, La Tianguis also serves as a haven for QTGNC youth to be themselves. One can attribute this to the type of clothing sold, the presence of other queer youth, and La Tianguis’ events, but one crucial element is the gender-inclusive writing and graffiti, which creates a sense of belonging amidst QTGNC exclusion and violence. Because Spanish is a gendered language, phrases such as “no estás solx” on the walls create a sense of belonging and comfort among gender-nonconforming people. While graffiti can affirm rights to the city and express political dissent (Caldeira (2012), La Tianguis demonstrates its role in fostering security and comfort within LGBTQ+ spaces in response to the historical relationship between language and exclusion.

Implications

In many parts of Latin America, the term “marica,” a derogatory word used against queer people, has been reclaimed to uplift low-income LGTBQ+ communities. For racialized and working-class Latin American queer people, the term “gay” is often associated with whiteness and assimilation, which is difficult for maricas to achieve because of their low-income status, race, femininity, etc. (Cerón-Cordova, 2015). Instead, maricas do not seek insertion within established capitalistic frameworks but rather aim to create their own alternative economies and social support structures (Cerón-Cordova, 2015).

The reclaiming of the term “marica” and the framing of La Tianguis as a “trans-marika-lencha” movement illustrate Miraftab’s (2009) concept of insurgent planning, where residents “do not constrain themselves to the spaces for citizen participation sanctioned by the authorities [invited spaces]; they invent new spaces and re-appropriate old ones where they can invoke their citizenship rights…” (p. 35). Through their spatial and social production of La Tianguis, queer youth are reclaiming “urban space by making something out of nearly nothing” (Oliver, 2018), highlighting the importance of considering queer youth as critical spatial actors in insurgent planning.

In addition, La Tianguis brings a new perspective to queer placemaking scholarship, which has tended to privilege white cisgender gay men and material-constant sites such as gay bars and nightclubs (Unipan 2021) while overlooking placemaking initiatives by low-income, racialized QTGNC folks. Unipan (2021) identifies two properties that develop different communities: “material/immaterial,” which refers to whether a space is physical or not, and “constant/transient,” which describes if a community has complete ownership of a space or instead gathers episodically. Originally, La Tianguis could have been understood as material-transient, but through its increasing popularity and graffiti, it has become material-constant as the place “retains the community’s identity even when members are not present” (Unipan, 2021). La Tianguis Disidente thus represents a different type of queer placemaking that we might call marica placemaking, led by racialized QTGNC people as they challenge mainstream queer placemaking efforts and seek to develop new and independent futures.

La Tianguis Disidente at La Glorieta de los Insurgentes. Photo Credit: Denisse Hernández. Source

Glorieta de los Insurgentes (La Tianguis is inside the white oval [underneath the highway]). Source

“No estás solx” Poster. Photo Credit: Xoch Quintero. Source

“If the state doesn’t take care of you, I will take care of you because I love you” Graffiti. Photo Credit: Sergio Morales

[Poster at the bottom-right] “Shut the voice of your privilege, we are diverse”. Photo Credit: @mueganxs [on Instagram].