On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was killed by three Minneapolis police officers. His death was the latest in a long line of black people dying at the hands of police, including the late-night shooting death of EMT Breonna Taylor by Louisville police in her own apartment and the death of Mike Ramos, an unarmed man of black and Latinx descent, by Austin police on April 24, 2020. For many, it was also reminiscent of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in February, who was chased and shot by two white men while jogging near his home. While Arbery was not killed by police officers, it was a harsh reminder that the possibility of racially motivated violence against people of color is always present in American society.

Since late May, protests in response to police brutality against people of color and other acts of racist violence have spread across the country. Many of the protests have been guided by the principles of non-violence as set down by Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and other civil rights leaders. At a virtual town hall organized by the organization My Brother’s Keeper, former President Barack Obama both decried the police violence that led to Floyd’s death and also called upon protesters to remain peaceful.

However, in some places there has also been violence, including rioting and looting either by protesters or by other parties. Determining where a protest ends and a riot begins (if there even is a clear distinction) is difficult. Some scholars even argue that a certain degree of violence is an inevitable part of American protesting. After all, one of the most famous protests in American history– the Boston Tea Party– was an act of material destruction.

Likewise, the act of rioting has been construed by some as a means of last resort when all other avenues of change, including voting and peaceful protests, have failed. In a recent interview, Rep. Maxine Waters described the riots in California in 1992 as “an explosion of a hopelessness being played out” and went on to compare the 1992 riots to the current situation. While she points out several similarities between the two periods of unrest, including the lack of trust in the police, she also sees an important difference between them—specifically that in the recent protests there have been many white people joining black people in calling out for racial equity. In her words: “That’s telling us something — that it’s not only black people fed up with the police Establishment.”

Using the resources listed here, we invite you to explore the complex role protests play in American politics with a special emphasis on the ongoing struggle for racial equality. In future blog posts, we will discuss less frequently recognized events of racial violence in American history and the tradition of LGBTQ+ activism (including the Stonewall Riots of 1969).

Please note: All annotations have been taken from the resource itself.

Books

Gottheimer, J., ed. (2003). Ripples of Hope: Great American Civil Rights Speeches. Link.

Including a never-before published speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., this is the first compilation of its kind, bringing together the most influential and important voices from two hundred years of America’s struggle for civil rights, including essential speeches from leaders, both famous and obscure. With voices as diverse as Cesar Chavez, Harvey Milk, Betty Friedan, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth, this anthology constitutes a unique chronicle of the nation’s civil rights movements and the critical issues they’ve tackled, from slavery and suffrage to immigration and affirmative action. This is an indispensable compilation of the words –the ripples of hope–that, collectively, have changed American history.

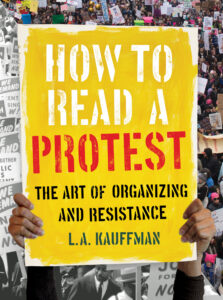

Kauffman, L. (2018). How to Read a Protest: The Art of Organizing and Resistance. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520972209

Films

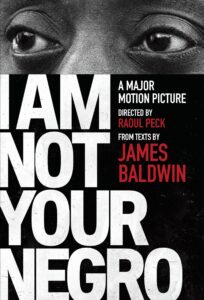

Peck, R., & Brown, J. (2016). I Am Not Your Negro. Documentary available on Kanopy. E-book available through UT Libraries.

An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. The book was to be a revolutionary, personal account of the lives and successive assassinations of three of his close friends–Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. At the time of Baldwin’s death in 1987, he left behind only thirty completed pages of his manuscript. Now, in his incendiary new documentary, master filmmaker Raoul Peck envisions the book James Baldwin never finished. The result is a radical, up-to-the-minute examination of race in America, using Baldwin’s original words and flood of rich archival material.

Speeches and Music

Seale, B., & Educational Video Group. (1973). Bobby Seale : Speech on Black Panthers Movement. Link.

Online Resources and Newspaper Articles

Jackson, K.C. (1 June 2020). “The Double Standard of the American Riot.” The Atlantic. Link.

“Today, peaceful demonstrations and violent riots alike have erupted across the country in response to police brutality and the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. Yet the language used to refer to protesters has included looters, thugs, and even claims that they are un-American. The philosophy of force and violence to obtain freedom has long been employed by white people and explicitly denied to black Americans.”

Hannah-Jones, N., et al. The 1619 Project. The New York Times Magazine. Link.

The 1619 Project is an ongoing initiative from The New York Times Magazine that began in August 2019, the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.

Texas After Violence Project (part of the UT Libraries Human Rights Documentations Initiative) Link.

In 2009, the Human Rights Documentation Initiative (HRDI) partnered with the independent, Austin-based nonprofit organization, Texas After Violence Project (TAVP), a human rights and restorative justice project that studies the effects of interpersonal and state violence on individuals, families, and communities. Its mission is to build a digital archive that serves as a resource for community dialogue and public policy to promote alternative, nonviolent ways to prevent and respond to violence. The HRDI is working with TAVP to ensure the long-term preservation and access of its digital video testimonies, transcripts and organizational records.

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy was a participant in the Stonewall Riots. Today, she is still an active supporter and advocate for transgender rights. She is currently Executive Director Emeritus of the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project, which helps and supports transgender women of color in prison or formerly incarcerated. The documentary focuses on her work as an activist and challenges faced by the transgender community by the LGBTQIA+ Community and by society as a whole.

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy was a participant in the Stonewall Riots. Today, she is still an active supporter and advocate for transgender rights. She is currently Executive Director Emeritus of the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project, which helps and supports transgender women of color in prison or formerly incarcerated. The documentary focuses on her work as an activist and challenges faced by the transgender community by the LGBTQIA+ Community and by society as a whole. Pride Denied tells the story of how corporate sponsors coopted the concept of LGBTQ pride, turning it into a feel-good brand and blunting its radical political edge. The film locates the origins of pride in sites of grassroots resistance and revolt, going back to the anti-police Stonewall uprising led by queer and trans people of color in 1969. It then traces how the deeply political roots of pride morphed into the depoliticized big-business spectacles of today — multimillion-dollar events designed to project an image of tolerance and equality rather than calling attention to the relationship between normative identity, power, and sexual repression.

Pride Denied tells the story of how corporate sponsors coopted the concept of LGBTQ pride, turning it into a feel-good brand and blunting its radical political edge. The film locates the origins of pride in sites of grassroots resistance and revolt, going back to the anti-police Stonewall uprising led by queer and trans people of color in 1969. It then traces how the deeply political roots of pride morphed into the depoliticized big-business spectacles of today — multimillion-dollar events designed to project an image of tolerance and equality rather than calling attention to the relationship between normative identity, power, and sexual repression. A new addition to the UT Libraries Collection, Marc Stein’s new book retells the story of the Stonewall Riots by presenting over 200 documents relating to the event, including gay-bar guide listings, political fliers, first-person accounts, state court decisions, and song lyrics.

A new addition to the UT Libraries Collection, Marc Stein’s new book retells the story of the Stonewall Riots by presenting over 200 documents relating to the event, including gay-bar guide listings, political fliers, first-person accounts, state court decisions, and song lyrics. Another new addition to the UT Libraries, the New York Public Library Archives published this book in honor of the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall. Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies photograph and document the LGBTQIA+ activism, protests, and history. Lahsen was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national organization for lesbians, art editor for

Another new addition to the UT Libraries, the New York Public Library Archives published this book in honor of the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall. Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies photograph and document the LGBTQIA+ activism, protests, and history. Lahsen was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national organization for lesbians, art editor for

Carter provides a very detailed historical narrative of the Stonewall Riots, starting with the history of the Greenwich Village and Christopher Street, through the monopoly of the Mafia on gay bars, and the reactions to the events that took place.

Carter provides a very detailed historical narrative of the Stonewall Riots, starting with the history of the Greenwich Village and Christopher Street, through the monopoly of the Mafia on gay bars, and the reactions to the events that took place.