By Brenna Wheeler

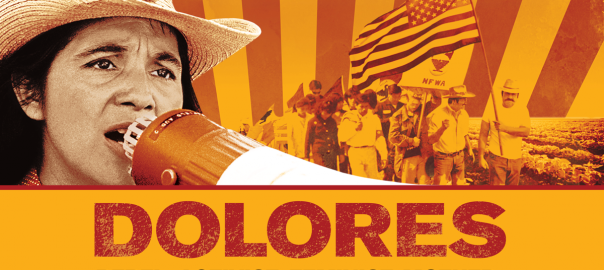

On September 10th, UT Libraries and the Latino Studies department are co-sponsoring a screening of the film “Dolores: Rebel, Activist, Feminist, Mother.” In collaboration with this event, the DAC blog would like to highlight some collection resources available on the work and life of Dolores Huerta.

Early Life

Dolores Huerta and her two brothers were raised in Stockton, California by their mother Alicia Chávez after her divorce from their father Juan Fernández, a coal miner who later became a politician in New Mexico. As a single mother Alicia supported herself and her children by working her way up through the food service industry until she owned a restaurant and a hotel. It was her mother’s “independence and entrepreneurial spirit” that would inspire Huerta’s feminism and activism. From a young age, Huerta joined her mother in becoming active in community civic organizations and local church events (Dolores Huerta Foundation; García 2008, pg. xvi). She continued being active in her community through high school. Soon after graduating, she earned a teaching credential from the University of Pacific’s Delta College in Stockton (Dolores Huerta Foundation).

In 1955, Huerta founded the Stockton branch of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which promoted civic participation in Spanish-speaking communities and focused on political and social concerns of working-class, urban, Mexican-American families in California and Arizona (“Huerta, Dolores Clara Fernandez (B. 1930)” 2013; Rose 2008, pg. 10). Through the CSO, Huerta met the activists Fred Ross and Cézar Chávez. In 1962, Chávez and Huerta left the CSO to begin the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in order to focus specifically on agricultural labor (García 2008, pg. xvii).

Labor Unions

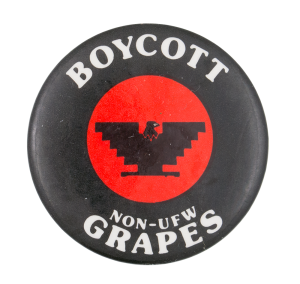

In the newly formed NFWA, Huerta and Chávez worked to gather a member base and set up the organization from their base of operations in Delano. The NFWA was quickly called upon by the AFL-CIO-supported union the Agricultural Workers’ Organizing Committee (AWOC) to honor the Delano Grape Strike of 1965 (Rose 2008, pg. 15). Despite NFWA’s small size, the new union voted to join the strike on Mexican Independence Day, September 16th (García 2008, pg. xvii). For five years, Huerta led strikes, directed boycotts, and negotiated collective bargaining until 1970, when the Delano and Coachella grape growers finally negotiated with the strikers to create new contacts meeting the union’s demands. Before the strike, growers utilized racial and ethnic tensions to divide workers, a tactic which Huerta and Chávez fought against by gathering support from a wide audience across the United States (Rose 2008, pg. 15-18). The strike’s success was partially due to the solidarity between AWOC (a large portion of which were Filipino-Americans), NFWA (a large portion of which were Mexican-Americans), and middle-class white supporters of the boycotts.

The strike would eventually lead to the merging of ALF-CIO and the NFWA into the new United Farm Workers Organizing Committee in 1966. Huerta became Chief Negotiator and Director of Boycotts, which gave her the responsibility of managing the boycotts against table grapes, lettuce, and Gallo Winery. These boycotts pushed for the passing of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (1975), which allowed California farm workers to collectively organize and bargain for better wages and working conditions, as well as establish the Agricultural Labor Relations Board. Later, United Farm Workers of America would become an independent affiliate of the AFL-CIO (“Huerta, Dolores Clara Fernandez (B. 1930)” 2013, Dolores Huerta Foundation).

Feminism

Huerta’s work with the grape boycotts involved directing the boycott in New York and later the entire East Coast. While in these areas, she came into contact with feminist activists like Eleanor Smeal and Gloria Steinem, who supported the farmworker’s cause. The feminist movement encouraged Huerta to challenge gender bias and sexism in her own organization and to openly discuss women’s issues, including childcare and sexual harassment in the workplace (Huerta and Rosenbloom 2019; Rose 2008, pg. 17-18). In an interview with Frontline, Huerta described counting the number of sexist remarks she heard during board meetings and then announcing the number at the end of the meeting. After she started doing this, the number dropped from fifty-eight instances to zero, and soon, the men would “check themselves” before the meetings began. Through such openness, workshops, and discussions with other women about their experiences, Huerta pushed for feminism within her own labor movement (Breslow 2013). In 1991, Huerta left the United Farm Workers to work with the Feminist Majority’s Feminization of Power Campaign to encourage Latina women to run for public office (“Huerta, Dolores Clara Fernandez (B. 1930)” 2013).

Activism Today

In 1993, Huerta returned as leader to the UFW after Chávez passed away, and today, she still acts as Vice-President Emeritus. She also currently runs the Dolores Huerta Foundation, which defines itself as a “community benefit organization which recruits, trains, organizes, and empowers grassroots leaders in low-income communities to attain social justice through systemic and structural transformation”. In recent years, she has won a series of awards for her activism, including The Eleanor Roosevelt Humans Rights Award from President Clinton in 1998, the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama in 2012, and being inducted into the California Hall of Fame in 2013 (Dolores Huerta Foundation). Even today, Huerta is still active in her work, speaking at various organizations, hosting workshops and trainings, and giving TED Talks.

References

Breslow, J.M. (2013). “Dolores Huerta: An ‘Epidemic in the Fields’.” from PBS: Frontline. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/dolores-huerta-an-epidemic-in-the-fields/

García, M.T. (ed.) (2008) A Dolores Huerta Reader. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Griswold del Castillo, R. and García, R.A. (2008) “Coleadership: The Strength of Dolores Huerta” in A Dolores Huerta Reader. Edited by Mario T. García. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Dolores Huerta Foundation. Retrieved from here.

“Huerta, Dolores Clara Fernandez (B. 1930).” (2013). In Suffrage to the Senate: America’s Political Women: an Encyclopedia of Leaders, Causes & Issues (3rd ed.). Edited by S. O’Dea. Amenia, NY: Grey House Publishing. Retrieved from here.

Huerta D. and Rosenbloom, Rachel. (2019). “Ask a Feminist: Dolores Huerta and Rachel Rosenbloom Discuss Gender and Immigrant Rights,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44, no. 2. Retrieved from here.

Rose, M. (2008) “Dolores Huerta: The United Farm Workers Union” in A Dolores Huerta Reader. Edited by Mario T. García. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Collection Highlights

Dolores (2018) [DVD, Streaming]

Dolores (2018) [DVD, Streaming]

“Dolores Huerta is among the most important, yet least known, activists in American history. An equal partner in co-founding the first farm workers unions with Cézar Chávez, her enormous contributions have gone largely unrecognized. Dolores tirelessly led the fight for racial and labor justice, becoming one of the most defiant feminists of the twentieth century. Includes Spanish subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.”

In Her Own Words

A Dolores Huerta Reader edited by Mario T. García [Book]

A Dolores Huerta Reader edited by Mario T. García [Book]

“Farm labor leader and civil rights advocate Dolores Huerta first worked with César Chávez as a community organizer in Mexican American areas of southern California in the mid-1950s. Chávez dreamed of organizing farm workers, and in 1962 he started the National Farm Workers Association. He asked Huerta to work with them, and in the next three years they recruited a number of members. This is the first book to focus on Dolores Huerta. Throughout six decades of activism, she has made her own history and has been part of major events in the history of the country. A Dolores Huerta Reader includes an informative biographical introduction, articles and book excerpts written about her, her own writing and speeches, and a recent interview with Mario García where she expresses her unbending dedication to social justice.”

The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers by Rick Nahmias, foreword by Dolores Huerta. [Book]

The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers by Rick Nahmias, foreword by Dolores Huerta. [Book]

“The Migrant Project includes the images and text of the traveling exhibition of the same name, along with numerous outtakes and an in-depth preface by Nahmias. Accompanied by a Foreword from United Farm Worker co-creator Dolores Huerta, essays by top farm worker advocates, and oral histories from farm workers themselves, this volume should find itself at home in the hands of everyone from the student and teacher, to the activist, the photography enthusiast, and the consumer.”

“Ask a Feminist: Dolores Huerta and Rachel Rosenbloom Discuss Gender and Immigrant Rights” in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society [Article]

“Ask a Feminist: Dolores Huerta and Rachel Rosenbloom Discuss Gender and Immigrant Rights” in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society [Article]

“For this edition of Ask a Feminist, Dolores Huerta—renowned labor organizer, immigrant rights activist, and feminist advocate—speaks with Rachel Rosenbloom, professor of Law at Northeastern University, about the role that gender plays in today’s struggles and social movements, especially those working on behalf of immigrants and workers. Drawing on her long history of organizing, Huerta offers insights on the contemporary political landscape—from the #MeToo movement to the fight for the DREAMers to opposition to Donald Trump. Huerta’s long history of fighting for social justice serves as a crucial guide for building a sustained and intersectional resistance.”

Documents from the Labor Movement

- Documents of the Chicano Movement edited by Roger Bruns [Book]

- “This book provides a variety of original source documents–from first-hand accounts to media responses to legislative texts–regarding the Chicano movement of the 1960s through 1970s that enable readers to better comprehend the key events, individuals, and developments of La Causa: Chicanos uniting to free themselves of liberation from exploitation, oppression, and racism.”

The sabotage and subversion of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act: a United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO [White Paper]

The sabotage and subversion of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act: a United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO [White Paper]- Collections of the United Farm Workers of America [Microfilm]

- “Collection includes: executive correspondence and meeting minutes, as well organizer’s reports from the field, testimony and speeches, boycott flyers, letters from supporters and autograph seekers, songs, and prayers, communications between Chavez and his organizers, the Kennedy’s, the Church hierarchy, civil rights leaders, union leaders, and Chicano militants.”

- Collections of the United Farm Workers of America. Papers of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, 1959-1966 [Microfilm]

- “Correspondence, clippings, reports, press releases, memoranda, newsletters, notes, and other materials relating to Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee.”

- Collections of the United Farm Workers of America: Series 2, Papers of the United Farm Workers of America Work Department, 1969-1975 [Microfilm]

- “Correspondence, clippings, memoranda, reports, financial papers, speeches, pamphlets, minutes, and other materials relating to the United Farm Workers Work Department.”

- Collections of the United Farm Workers of America: Part 2, 1965-1992, Office Files of the President of the United Farm Workers of America [Microfilm]

- “Collection includes: executive correspondence and meeting minutes, as well organizer’s reports from the field, testimony and speeches, boycott flyers, letters from supporters and autograph seekers, songs, and prayers, communications between Chavez and his organizers, the Kennedy’s, the Church hierarchy, civil rights leaders, union leaders, and Chicano militants.”

- National Farm Workers Association Records, 1960-1967 [Microfilm]

- “Organized into the following series: I. General correspondence files, 1962-1966, boxes 1-2. II. Correspondence with NFWA members files, 1962-1966, boxes 3-4. III. General topic files, 1960-1967 ; arranged alphabetically and chronologically.”

- National Farm Workers Association Records, 1960-1967 [Microfilm]

- “Organized into the following series: I. General correspondence files, 1962-1966, boxes 1-2. II. Correspondence with NFWA members files, 1962-1966, boxes 3-4. III. General topic files, 1960-1967 ; arranged alphabetically and chronologically.”

- Papers of the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, 1959-1970 [Microfilm]

- “Position paper in support of the United Farm Workers of America” Researched and Prepared by Judy Elders. [Book]

- “Adopted by the Houston Metropolitan Ministries Board of Directors, August 5, 1974.”

- The Texas Farm Worker Boycott Newsletter by the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO [Book]

- “Description based on: #27, published in 1975”

- The Texas Farm Worker Newsletter [Book]

- “Illegal Alien Farm Labor Activity in California and Arizona” prepared by the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO [Book]

- Huelga: a Film (c. 1966) by the United Farm Workers of America [Video]“Depicts the 100 mile protest march of the migrant farm workers from Delano to Sacramento, California.”

- El Malcriado: the Voice of the Farm Worker [Serial] English, Español

- “Issued as the official voice of the United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO.”

- No Grapes (1992) [Video] English, Español

- “Exposes the dangers of pesticides that are used on grapes in California and the health hazards to the farm workers and their children who work in the vineyards.”

- Si se puede! [CD]

- “An anthology of original songs composed by actual members of the UnitedFarm Workers and by others [who] have long supported their struggle for justice and dignity in the agricultural fields of America”

Scholars on Huerta

¡Sí, Ella Puede!: the Rhetorical Legacy of Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers by Stacey K. Sowards [Book]

¡Sí, Ella Puede!: the Rhetorical Legacy of Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers by Stacey K. Sowards [Book]

- “In this new study, Stacey K. Sowards closely examines Huerta’s rhetorical skills both in and out of the public eye and defines Huerta’s vital place within Chicana/o history. Referencing the theoretical works of Pierre Bourdieu, Chela Sandoval, Gloria Anzaldúa, and others, Sowards closely analyzes Huerta’s speeches, letters, and interviews. She shows how Huerta navigates the complex intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, language, and class through the myriad challenges faced by women activists of color. Sowards’s approach to studying Huerta’s rhetorical influence offers a unique perspective for understanding the transformative relationship between agency and social justice.”

- Dolores Huerta: Labor Leader and Civil Rights Activist by Robin S. Doak.[Book]

- “Born on April 10, 1930, Huerta learned to be outspoken at a young age from her mother, who was a businesswoman and an activist. As a young woman, she battled segregation and pushed for better public services through the Community Service Organization, which she co-founded. Huerta soon realized that the needs and rights of farmworkers needed support. She worked with Cesar Chavez, a fellow activist for farmworkers, to organize the farmworkers into a single union. From organizing boycotts to lobbying for the farmworkers’ job conditions, Huerta relentlessly strove to help others.”

- Dolores Huerta Stands Strong: the Woman who Demanded Justice by Marlene Targ Brill [Book]

- “Dolores Huerta Stands Strong follows Huerta’s life from the mining communities of the Southwest where her father toiled, to the vineyards and fields of California, and across the country to the present day. As she worked for fair treatment for others, Dolores earned the nation’s highest honors. More important, she found her voice.”

- Chicana Leadership: the Frontiers Reader edited by Yolanda Flores Neimann et al. [Book, eBook]

- “Chicana Leadership: The “Frontiers” Reader breaks the stereotypes of Mexican American women and shows how these women shape their lives and communities. This collection looks beyond the frequently held perception of Chicanas as passive and submissive and instead examines their roles as dynamic community leaders, activists, and scholars.”

- A Crushing Love: Chicanas, Motherhood, and Activism (2009) [DVD]

- “A documentary that honors five mothers who have raised families and have made important contributions as workers, activists, educators, leaders, and who effect broad-based social change.”

- La Causa: the Migrant Farmworkers’ Story by Dana Catharine de Ruiz and Richard Gutierrez [Book]

- “Describes the efforts in the 1960s of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to organize migrant workers in California into a union which became the United Farm Workers.”

- Dolores Huerta by Rebecca Thatcher Murcia [Book]

- “This special series focuses on the unique contributions Hispanics have made in the United States from the earliest Spanish explorers to the many successful Latinos in contemporary America. Each book provides historical and factual easy-reading stories. The books are jam-packed with information and contain between 7500 and 9000 words. Along with Cesar Chavez established the United Farm Workers to protect the rights of farm workers.”

- Dolores Huerta: General Bibliography and Short Biography by Denise Guckert [Book]

Have recommendations of your own? Let us know about them in the comments!

Dolores (2018) [

Dolores (2018) [ A Dolores Huerta Reader

A Dolores Huerta Reader The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers

The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers “Ask a Feminist: Dolores Huerta and Rachel Rosenbloom Discuss Gender and Immigrant Rights” in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society

“Ask a Feminist: Dolores Huerta and Rachel Rosenbloom Discuss Gender and Immigrant Rights” in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society The sabotage and subversion of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act: a United Farm Workers of America

The sabotage and subversion of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act: a United Farm Workers of America