I. Artist: Filippo Lauri, born in 17th century Rome, was an artistic protégé who followed in the footsteps of his brother (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Although having painted a small number of altar-pieces for churches, his most notable works involved those revolving around myth (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Some important pieces comparable to those we have studied this year include “The Punishment of Marsyas,” “Venus and Adonis,” and “The Rape of Europa” among others (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Lauri was also known for painting images that were housed in palaces around Rome (Blanton Museum of Art Collections, n.d.).

I. Artist: Filippo Lauri, born in 17th century Rome, was an artistic protégé who followed in the footsteps of his brother (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Although having painted a small number of altar-pieces for churches, his most notable works involved those revolving around myth (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Some important pieces comparable to those we have studied this year include “The Punishment of Marsyas,” “Venus and Adonis,” and “The Rape of Europa” among others (Bryan, 1889, 25-26). Lauri was also known for painting images that were housed in palaces around Rome (Blanton Museum of Art Collections, n.d.).

II. Date: Circa 1671 (Blanton Museum of Art Collections, n.d.)

III. Location on Campus: Blanton Museum of Art

IV. Acquisition: As part of the Suida-Manning Collection, this painting arrived along with seven hundred other works in 1999 to the Blanton (Dobryzinski, 1998). Amassed by famous art historians William Suida and Robert and Bertina Suida-Manning, the collection comprises of various works by European artists spanning the 14th to 18th centuries (Dobryzinski, 1998). Robert Manning, a native of Texas, expressed prior to his death his desire for the collection to remain intact in a Texan institution and evaluated the Blanton by inviting its then-curator to his New York residence where many of the paintings were on display (Dobryzinski, 1998). His daughter, Ms. Dolnier, donated part of the collection to the Blanton. She emphasized her preference for the collection’s placement in a university in contrast to a museum like the Metropolitan in New York since it would garner much greater appreciation instead of landing in storage (Dobryzinski, 1998). Value is also derived from the artwork in the university museum due to its ideal nature for student-driven study and research involving Renaissance and Baroque art (Dobryzinski, 1998). Today, fifty of these works, including Lauri’s, are on permanent exhibition (Ura, 2013).

IV. Description: Oil painting on canvas 59 cm x 71.2 cm (23 1/4 in. x 28 1/16 in.)

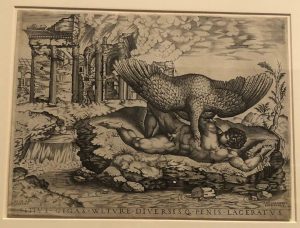

Lauri explicitly depicts the mythological event of Jupiter and Juno’s wedding. Here, it is clear that he uses as inspiration Servius’ account of the myth in his commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid, which goes as follows. Mercury was said to have invited all the gods, humans, and animals to the wedding of his father. The nymph, Chelone, elected not to attend due to her arrogance, which greatly angered Mercury. He decided to discard Chelone’s house into a river while transforming her into a turtle or tortoise (Servius, Ad. Virgil’s Aeneid, i.509). This moment of metamorphosis is the subject of Lauri’s artistic rendition. In relation to mythological variants of this tale, one of the first accounts appears in Aesop’s Fables in which it is often coined “Zeus and the Tortoise.” This version of myth is responsible for birthing important ideals about the meaning and social constructs surrounding the oikos. According to Aesop, Zeus invited the animals to his wedding who all arrived except for the tortoise. His curiosity led him to inquire about her absence to which she replied, “Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home.” Zeus’ characteristic anger is displayed when he punishes her by ordering her to carry her house (Aesop, Fables, 508). The quote is particularly interesting in that it influenced the writings of Christian classical scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1523) who included a version of the tortoise’s saying in his book of adages. Scholars or writers such as Plutarch and Cicero utilized the quote in order to make conclusions about the essence of a “loved home” in which often the wife must ascribe to her duties as a homemaker (Erasmus, 1523). Aesop’s version of the myth also functions in an etiological fashion in order to explain the nature of the tortoise shell. In fact, khelone signifies “tortoise” in Greek (Aesop, Fables, 508). Taking some artistic liberty, Lauri strays slightly from both recorded versions of the tale in that the main condemner of Chelone is Juno while both Mercury and Jupiter occupy spaces further away from the action (Blanton Museum of Art Collections, n.d.). One might wonder why Lauri would choose such a rendition when Juno’s main role in mythology is often subordinate to Jupiter as his consort (Buxton, 2016, 70-71). It is possible that Lauri is attempting to allude to Juno’s vindictive nature that frequently places her in a role to catalyze the metamorphosis of various characters (Buxton, 2016, 70-71). In this particular instance, the Greek conceptions of timḗ, hubris, and nemesis have particular relevance. As two powerful gods, Juno and Jupiter place great importance on their timḗ. Chelone’s lack of proper reverence to the Olympian gods by failing to attend their wedding is a direct attack and damage to their timḗs, which constitutes an act of hubris. In terms of hubris, as a nymph, Chelone fails to “know [herself]” and her place on the religious hierarchy by mocking the union of gods far more honored than her. At this point, Chelone is expected to incur nemesis, or retribution, in order for Juno and Jupiter to restore their timḗs. By transforming Chelone into a turtle, the punishment does appear severe yet is necessary if there is to only be one winner. The pleading expression Lauri plasters on Chelone’s face and outstretched hand as she attempts to escape her fate in the midst of her transformation is a testament to the lack of mercy the gods display. Juno may be the key player here because she also has a specific responsibility to uphold the value of marriage, which remains her sphere of influence, and a nymph like Chelone clearly specifically damages Juno’s timḗ by mocking a wedding union (Buxton, 2016, 70-71). When observing the manner in which Lauri depicts the gods, it is important to take artistic era into context. The seventeenth century is representative of a time period where artists were highly educated, and classical mythology had great cultural relevance (Brenner, 1996). In fact, the circulation of texts that defined visual symbols allowed for easy recognition of artistic entities such as Jupiter’s eagle or Juno’s peacock (Brenner, 1996). Interestingly, Lauri does not depict Juno in a traditional fashion. Instead of a modest and clothed appearance, she is likened more to Venus in her exposed state with only a veil slightly draping over her body (Morford, Lenardon, and Sham, 2014). Mercury, in position behind Jupiter, possesses the traditional attributes that were often associated with him in ancient art. He appears as a young, beardless man with a winged hat and caduceus, or herald’s wand, in his left hand, which was typical of Mercury in Roman iconography (“Hermes”, n.d.). The staff symbolizes Mercury’s role as the messenger of the gods and his relation to commerce or trade (Hornblower and Spawforth, 1996). Behind Hera, Lauri illustrates Cupid, the god of love, in Roman fashion as a young winged boy. Although Cupid had various functions in post classical art, here he is most likely a celebrant of the nuptial scene, also conveyed by the young appearance of both Juno and Jupiter (“Eros”, n.d). Finally, taking the oval shape of the canvas into account, it is possible the artwork was made to be displayed above a door or window indicating its decorative function (Blanton Museum of Art Collections, n.d.). This piece is displayed along with another piece of Lauri’s, which depicts the famous mythological metamorphosis account of “Venus and Adonis.” The similar shape and frame indicate that the two pieces may have been part of a series.

Bibliography

1984. “Aesop Fables.” Franklin Center, PA: Franklin Library.

Blanton Museum of Art Collections. n.d. “Mercury Transforming Chelone into a Turtle.” Accessed April 18, 2019.

Brenner, Carla. 1996. “The Inquiring Eye” Classical Mythology in European Art Teaching Packet.” Washington DC: National Gallery of Art.

Bryan, Michael. 1889. “Dictionary of Painters and Engravers: Biographical and Critical, Volume 2.” Edited by Walter Armstrong and Robert Edmund Graves, 25-26. London: George Well and Sons.

Buxton, Richard. 2016. “The Complete World of Greek Mythology.” London: Thames & Hudson

Dobryzinski, Judith. 1998. “Art Museum in Texas Gets Trove of 700 Works.” New York Times, November 12, 1998.

Erasmus, Desiderius. 1536. “The Adages of Erasmus.” Selected by William Barker. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Filippo Lauri, “Mercury Transforming Chelone into a Turtle,” Blanton Museum of Art Collections, accessed April 26, 2019.

Hornblower, Simon and Anthony Spawforth, ed. 1996. The Oxford Classical Dictionary, third ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

McDonough, Christopher Michael, Richard Edmon Prior, and Mark Stansbury. 2004. “Servius Commentary on Book Four of Virgils Aeneid”. Mundelein: Bolchazi-Calducci Publishers.

Morford, Mark, Robert J. Lenardon, and Michael Sham. 2014. “Classical Mythology.” New York: Oxford University Press.

Theoi n.d. “Eros.” Accessed April 23, 2019.

Theoi n.d. “Hermes.” Accessed April 22, 2019.

Ura, Alexa. 2013. “Foundation to Transfer Full Ownership of Suida-Manning Collection to Blanton in 2016.” The Daily Texan, April, 29, 2013.

Written by Palak Diwanji

Artist: Harootian was born in Armenia. Due to the mass genocide by the ruling Turks his family moved to Russia initially but ended up immigrating to the United States. This gave Harootian the opportunity to gain an education where he studied painting and developed the early skill of watercolor painting. After finishing his schooling, he moved to Jamaica where he befriend Edna Manley who greatly influenced his work leading to his love of carving. His sculptures ranges “being made from” wood, bronze, and stone carvings.

Artist: Harootian was born in Armenia. Due to the mass genocide by the ruling Turks his family moved to Russia initially but ended up immigrating to the United States. This gave Harootian the opportunity to gain an education where he studied painting and developed the early skill of watercolor painting. After finishing his schooling, he moved to Jamaica where he befriend Edna Manley who greatly influenced his work leading to his love of carving. His sculptures ranges “being made from” wood, bronze, and stone carvings. Artist: Jacques Blanchard (1600-1638), sometimes referred to as “French Titian”, is best known for his small religious and mythological paintings. Blanchard’s paintings deviated substantially from his contemporaries’; specifically, Blanchard’s painting style was softer and gentler with color and light than works of the Mannerist period that preceded him, and his choice of more sensual subject matter was unorthodox for the time period. But despite his deviance in style from many other famous contemporaries, the influence of the early baroque style on Blanchard’s painting is clearly observed in Danaë.

Artist: Jacques Blanchard (1600-1638), sometimes referred to as “French Titian”, is best known for his small religious and mythological paintings. Blanchard’s paintings deviated substantially from his contemporaries’; specifically, Blanchard’s painting style was softer and gentler with color and light than works of the Mannerist period that preceded him, and his choice of more sensual subject matter was unorthodox for the time period. But despite his deviance in style from many other famous contemporaries, the influence of the early baroque style on Blanchard’s painting is clearly observed in Danaë.