Information about the Tour

The tour will depart from the Blanton Museum. The tour will last approximately one hour. There will be three tours: 10:00 am, 11:00 am, and 1:00 pm. Please be aware that the walk will be a little less than a mile long and we will be walking up and down steps. You’re welcome to leave the tour at any time you see fit.

I. SOUTH MALL

Littlefield Fountain

Google map for Littlefield Fountain can be found here.

Between the South Mall and W. 21st street stands the iconic Littlefield Fountain. Since its completion in 1933, Littlefield Fountain has been the most widely recognized statuary on UT’s campus. It is a powerful amalgamation of Greek iconography that have been appropriated to create a World War I monument. It was carried out by Pompeo Coppini, an Italian-born sculptor living in San Antonio. He depicted Columbia, the symbol of the American spirit, standing on the bow of a ship being pulled by three sea horses. Behind her are two soldiers one representing the Army and the other the Navy. By depicting Columbia traveling victoriously across the waters in her defense of liberty, Coppini intended the sculpture to create an image of a strong, unified America.

The winged Columbia standing with arms raised up borrows from the iconography of the Greek goddess of victory, Nike. In Greek vase paintings, Nike is depicted driving the battle chariot for Zeus in the Gigantomachy, the war between the Olympians and the Giants. In myth, Nike is famous for siding with Zeus and the Olympians in their victorious war against the previous generations of gods known as the Titans. Another classical influence for Coppini’s Columbia standing on the eagle prow of a ship is perhaps the famous Hellenistic sculpture called the Nike of Samothrace, whose Nike also appears to be standing on the prow of a ship. Instead of holding a phiale (a libation bowl), Columbia is depicted holding the torch of liberty in her right hand and the palms of peace in her left hand.

The Mermen in the fountain are anthropomorphic figures which are controlling sea horses, known as Hippocampi (Gr. Hippo = horse + campi = sea monsters). In ancient Greek and Roman art, the hippocampi were traditionally depicted as half horse/half fish creatures pulling the chariot of the Greek god of the sea, Poseidon. Instead of the horses which pull the quadriga of Nike, Coppini has replaced them with hippocampi to emphasize the discovery of America and the United States’ power being via the sea.

There are numerous inscriptions on the monument. On the left side, the ship is inscribed with “Columbia – November XI MDCCCCXVIII.” The Roman numerals “XI MDCCCCXVIII” stand for November 11, 1918, which marks the end of World War I. On the right side, the ship is inscribed with “Columbia – April MD CCCCXVII”, April 1917, which marks the date when the United States entered World War I.

Columbia faces the statue of Lady Liberty on top of the Texas State Capitol, which seems to emphasize UT’s relationship to the government of Texas. Inscribed in the limestone flanking the backside of the statue are the words of the famous Roman statesman, Cicero (Philip., 14.12), written in Latin: “Brevis a natura nobis vita data est, at memoria bene redditae vitae sempiturna,” which is translated, “A short life has been given to us by nature, but the memory of a life honorably offered is everlasting.”

A more detailed account of the history of Littlefield Fountain can be found here.

The Main Building (also known as ‘The Tower’)

Location of the Main Building on campus can be found here via Google Maps.

UT’s Main Building is full of symbols paying homage to the Greco-Roman world.

The inscription on the Main Building beneath the Tower, “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free”, comes from an English translation of the Greek in the Gospel of John 8:32 (καὶ γνώσεσθε τὴν ἀλήθειαν, καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια ἐλευθερώσει ὑμᾶς). The words are attributed to Jesus Christ, when he was explaining that if one were to live according to his words that person would become his disciple. The ‘truth’ Jesus is referring to in this passage appears to be the revelation of who he is. According to the context of this passage in the Gospel of John, the ‘freedom’ that this truth brings is salvation from death and the slavery to sin that Jesus is offering to those who follow his teachings. Taken in the context of the iconography of the Tower and Main Building, the ‘truth’ spoken of in this passage from the Bible has been appropriated to mean ‘knowledge’ and ‘truth’ in the general context of academic pursuits. The reinterpretation of this biblical passage is reinforced by the academic iconography that adorns the Main Building, namely the ancient alphabets (Egyptian Hieroglyphs and Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek and Latin alphabets) on the Tower and the seals of famous universities .

The symbolism of the Greek temple-like structure at the top of the UT Tower is often overlooked by the casual passerby. The location of the Greek temple-like structure at the top of the Tower suggests that the great intellectual achievements of Greco-Roman world are something the University of Texas aspires to. In some respects, the Tower itself looks like some of the modern artistic interpretations of the appearance of the famous Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria, which stood guarding the city of Hellenistic Alexandria and its world-renowned library. The Tower’s resemblance to the Pharos Lighthouse would be rather fitting given the Tower was originally intended to house the university’s main library.

Battle Hall

Location of Battle Hall on campus can be found here via Google Maps.

Battle hall is named after the Professor of Classics and 6th President of the University of Texas. William James Battle served as President of UT from 1914-1916. He joined the university in 1893 as an Associate Professor of Greek. Some of the plasters now displayed in the William J. Battle Collection of Plaster Casts were placed along the walls of the auditorium he would lecture in, which is why this lecture hall was known as “The Greek Room.” In 1908, Battle became the Dean of the College of Arts. He became the President of the UT in 1914. After serving a rather tumultuous presidency that even threatened his position as President, Battle left UT to teach at the University of Cincinnati. He later returned to UT in 1920 as Professor of Classical Languages. Some of his most indelible influences on the university were while he was Chairman of the Faculty Building Committee, a role he served for nearly three decades until 1948. Battle’s profound influence on UT’s campus is evident to this day, most notably the design and symbolism of the Main Building and its Tower, which was spearheaded by Battle. Some of Battle’s other noteworthy contributions to the university were the foundation of the University COOP (1898) and the design of the university’s seal (1901). Additional information on William Battle can be found via the Texas State Historical Association.

Located beside the Tower, Battle Hall is quite conspicuous due to its ornate facade richly adorned with colorful symbols. This is particularly evident around the windowed balconies on the building.

If you look closely at the repeated images, around the windows you will observe the Roman god Janus. Janus is an appropriate image for doors since, for Romans, he is a god of beginnings/end, transitions, and doorways. He was commonly depicted as a two-faced god who looks to the past and the future. Janus was seen as presiding over war and peace, which can be observed with the function of the doors of his temple in Rome. These temple doors were open during times of war and closed during times of peace. Janus is conventionally associated with the month we call January, which derives its name from the Latin word for doorway, ianua. January is symbolically the doorway to a New Year since its inclusion as the first month of the year dating back to the Julian Calendar, which was established on January 1st 45 BC.

Above each of the windowed balconies on Battle Hall are a series of medallions with images representing the signs of the Zodiac. It is important to bear in mind that knowledge of the Zodiac signs was not connected with the kind of mundane prophetic statements associated with reading one’s horoscope. For centuries, the Zodiac was understood as the movement of different constellations of stars whose position in the night sky indicated the passage of time and was used as a means of navigating. Knowledge of these constellations was also a fundamental part of medical education from the inception of medical universities in Italy. Greek myths were often associated with these constellations.

In some Greek constellation myths, Sagittarius is said to represent the centaur Chiron. During Hercules’ battle with a group of unruly centaurs, Chiron was said to have been accidentally hit by one of Hercules’ errant arrows. The arrow, which had been dipped in the poisonous blood of the Lernean Hydra, caused incurable suffering to Chiron. Unfortunately for Chiron, he was immortal making him unable to find release in death. Therefore, Chiron offered himself as a substitute for Prometheus, who had been punished by Zeus for his disobedience of giving fire to mortals (Prometheus was chained to a rock in Tartarus where he was constantly tormented by an eagle that daily consumed his liver). In recognition for Chiron’s sacrifice, Zeus honored Chiron by placing him in the stars.

II. WEST MALL

Lady Liberty/Athena on Main Building

UT’s Main Building is full of symbols paying homage to the Greco-Roman world. The figure above the window resembles Athena (Roman name Minerva). It is often identified as Lady Liberty (of Texas). This interpretation is partially based on the single star above her head, which suggests that she is associated with the Lone Star State. Lady Liberty is a personification of freedom commonly seen in iconography for the American Revolution. Lady Liberty is an abstraction of the goddess Athena, and therefore, the two figures often bear a striking resemblance to each other in artwork. This would make sense considering Athena was viewed as the patroness of the democratic government of Athens. And the martial nature of Athena is also evident in the depictions of Lady Liberty’s participation in democratic revolutions such as the image of Lady Liberty stamping out tyranny in The Apotheosis of George Washington in the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building.

Athena’s Owl on the Union Building

Location of the Union on campus via Google Maps.

In Greek iconography, the owl is an attribute of the goddess of wisdom, Athena (Minerva to the Romans). Subsequently, it is commonly used as a symbol of knowledge and wisdom in the European tradition. The owl of Athena at the Union (Commons) is situated among a number of symbols germane to the state of Texas (i.e. Jackrabbit, Rattlesnake, Roadrunner, Horned Toad, Cacti, and the Longhorn). Athena’s owl being situated between the words “Arts” and “Sciences” suggests that the acquisition of wisdom is the element that unifies the arts and sciences at the UT.

III. HOGG MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM

Greek Masks of Comedy, Tragedy, and Satyr

Location of Hogg Memorial Auditorium on campus can be found here via Google Maps.

Located behind the Tower and the Union is the Hogg Memorial Auditorium. The Hogg Memorial Auditorium was designed by the famed French architect Paul Cret, who also was responsible for the design of the Tower. Upon its completion in 1933, the building became the first theater on the school’s campus. The auditorium was named after James Stephen Hogg, the first native-born Governor of Texas. Information about the Hogg Memorial Auditorium’s rich history can be found here.

Greek theater consisted of three different dramatic genres: tragedy, satyr, and comedy. All three of these dramatic genres are represented by the three different personas/dramatic masks on the facade of the Hogg Memorial Auditorium. To get an appreciation for some of the basic differences between ancient Greek and modern dramas, a brief description of Greek dramatic performances has been provided in the following:

The most important presentations of tragedy at Athens took place once a year as part of a competition at the city’s main festival in honor of the god Dionysus. For this festival, one of Athens’ magistrates chose three playwrights to present four plays each. Three were tragedies and one a satyr play, the latter so named because it featured actors portraying the half-human, half-animal (horse or goat) creatures called satyrs. Satyr plays presented versions of the solemn stories of tragedy that were infused with humor and even farce. A board of citizen judges awarded first, second, and third prizes to the competing playwrights at the end of the festival. The performance of Athenian tragedies bore little resemblance to conventional modern theater productions. They took place during the daytime in an outdoor theater sacred to Dionysus, built into the slope of the southern hillside of Athens’ Acropolis. This theater of Dionysus held around 14,000 spectators overlooking an open, circular area in front of a slightly raised stage platform. To ensure fairness in the competition, all tragedies were required to have the same size cast, all of whom were men: three actors to play the speaking roles of all male and female characters and fifteen chorus members. Although the chorus’ leader sometimes engaged in dialogue with the actors, the chorus primarily performed songs and dances in the circular area in front of the stage, called the orchestra (“dancing area”). Since all the actors’ lines were in verse with special rhythms, the musical aspect of the chorus’ role enhanced the overall poetic nature of Athenian tragedy.

– Thomas R. Martin, An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called Muses. The Muses were described as the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory). Overtime, the different forms of poetry, music, and drama became associated with specific Muses. The Muse for tragedy was called Melpomene and the Muse for comedy was called Thalia.

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called Muses. The Muses were described as the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory). Overtime, the different forms of poetry, music, and drama became associated with specific Muses. The Muse for tragedy was called Melpomene and the Muse for comedy was called Thalia.

Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

A ‘satyr’ was the term for a mythical creature associated with Dionysus. It was also the term used for a short burlesque play performed after a series of three tragic plays. The satyr play kept with the general theme of the three tragedies by poking fun at the plight of the characters in the series of tragedies. In keeping with the uncivilized nature of the mythical creature also called a satyr, actors in these plays were described as wearing large phalli to create a comic effect. The fact that the Hogg Auditorium has included the face of a satyr is highly unusual since most modern theaters only depict the Greek dramatic masks for comedy and tragedy when paying homage to their classical foundations.

IV. HONORS QUADRANGLE

Diana of the Chase

Location of this statue can in Google Maps.

Tucked away in the honors quadrangle between Blanton, Littlefield, Andrews, and Carothers dormitories, stands a statue of the Greek goddess of the hunt, Artemis (Diana to the Romans). The statue was originally installed by William Battle in a niche in the library in Battle Hall. Later, it was moved to its current location among the honors dorms. Given Diana’s mythical association as a protector of young women, the statue’s subject matter was probably considered appropriate for it to be located next to the all-female dormitories that enclosed the quadrangle.

This hidden treasure of the university was created by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington. Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Diana of the Chase was first modeled in 1922. As legend has it, an 18-year-old Bette Davis posed for this statue. Diana of the Chase has been cast many times, appearing at institutions around the world such as Columbia University in New York City, Audubon Park in New Orleans, Palacio de Bellas Artes in Havana, Cuba, Jardin des Lices in Blois, France, and the Jardin Fuente de Diana in Madrid, Spain. UT’s statue is from a 1927 casting. Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Diana of the Chase represents her long-term engagement with outdoor statuary that often focused on two strong female figures, Joan of Arc and Diana. Diana of the Chase elegantly depicts a partially nude Diana pointing her bow toward the heavens with a hunting dog eagerly jumping upward.

In some ways, the statue is a striking departure from the Greco-Roman statues of Artemis/Diana, which typically depict Artemis as a young woman clothed in a short dress holding a bow in hand and often accompanied by a stag deer. Perhaps Huntington’s choice to depict Artemis naked with a hunting dog is meant to remind one of the Greek myth of the death of Actaeon. According to Apollodorus (3.30 ff), while hunting with his dogs, Actaeon happened upon Artemis bathing. The insult of being seen naked by a mortal male could be construed as a threat to Artemis’ virginity, which she vigorously protected. Artemis punished Actaeon by changing him into a deer and having his dogs tear him apart. Taken in this context, the naked Artemis in UT’s quadrangle is a fearful image for any male who may have wandered into this ‘sacred space.’ The upward aim of Artemis’ bow is another departure from classical iconography. Perhaps Huntington is suggesting that Artemis’ heavenward aim points to the heights women can and should aspire to. Or perhaps, Artemis’ upward bow is aimed at Zeus, and thereby symbolizing a female rejection of patriarchal rule in general.

V. WAGGENER HALL

Google map for Waggener Hall can be found here.

Our tour ends at Waggener Hall (the side facing the Tower). Waggener Hall was named after the University’s first President, Leslie Waggener. The building was designed by Paul Cret, and it was constructed in 1931. Constructed out of white limestone, multi-colored brick, and red-tile roof, Waggener blends with the other Mediterranean Renaissance-style buildings that Cret designed.

Photo by Marsha Miller/The University of Texas at Austin

Although there are numerous classical architectural features on Waggener Hall, the 26 medallions at the top of the building do not pay homage to the Greek and Roman world. These medallions represent the chief exports of Texas at the time of its construction (e.g. cotton, oil, cattle, lumber, etc.). These symbols reveal that Waggener hall was originally designed to house the School of Business Administration. Waggener Hall is now home to the Department of Classics, which is where UT students learn to read Greek and Latin, study Greco-Roman history, and learn about archaeology and ancient scripts. The Department of Classics’ main administrative office is located in Room 123 on the first floor. Next to the office is the Classics Lounge, which hosts department meetings and colloquia. The ground floor of Waggener Hall houses the Classics Library and its annex, the Visual Resources Collection, the Institute of Classical Archaeology, and the office of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory.

A history of Waggener Hall can be found here.

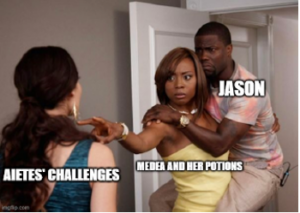

Theogony. If you need a smile and a laugh, or a quick summary of an ancient epic poem, please have a look at the link to Epic Mythomemologies on the website.

Theogony. If you need a smile and a laugh, or a quick summary of an ancient epic poem, please have a look at the link to Epic Mythomemologies on the website.

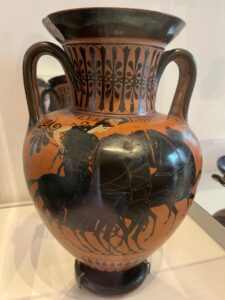

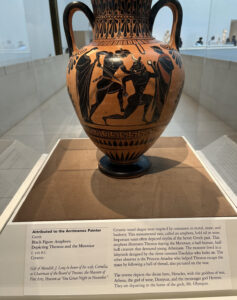

Black figure image of Theseus and the Minotaur on a Amphora dating to c. 520 BC

Black figure image of Theseus and the Minotaur on a Amphora dating to c. 520 BC