I. Creator

Flora was painted by Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), an Italian Baroque painter famous for his elegant, dynamic mythological and allegorical scenes (Blanton Museum of Art). He helped shape the early Rococo style with his soft, luminous colors and dramatic compositions (Royal Academy of Arts 2025). Ricci mainly worked in Venice, Florence, and London, eventually becoming one of the most influential Venetian painters of the early 18th century. His artistic style incorporated Venetian colorism with Rococo elegance, often depicting mythological subjects, pastoral deities, and allegorical figures (Bowron). Ricci’s paintings of classical gods and goddesses were often approached in a lighter, more colorful way compared to other painters’ interpretations of traditional mythological themes. He added emotional warmth and idealized beauty to his work, which are qualities clearly evident in Flora.

II. Date of Creation

The painting was created between 1712 and 1716, during the time Ricci was turning

increasingly toward mythological allegories (Bowron 1994).

III. Location on UT Campus

Flora can be found at the Blanton Museum of Art, located on the University of Texas at Austin campus. It is displayed in the museum’s European Art Gallery, among other Baroque and Rococo works (Blanton Museum of Art 2020).

IV. When and Why the Object Was Placed on UT Campus

Flora became a part of the Blanton Museum’s collection to contribute to a representative group of Baroque and Rococo paintings. The painting was meant to reinforce the museum’s holdings in Italian art, offering students and visitors the opportunity to engage directly with mythological subjects represented by influential European artists (Blanton Museum of Art). Ricci’s Flora opens the floor for entry into the world of classical mythology, Venetian painting, and early modern uses of ancient gods.

V. Type of Artwork

According to the Blanton Museum of Art, Flora is a large-scale oil painting on canvas,

measuring about 49 × 60.5 inches (Blanton Museum of Art). Ricci’s soft brushwork, pastel

tones, and idealized figure portray the shift from Rococo to his focus on sensuality and beauty.

VI. Description and Interpretation

When looking at Ricci’s Flora, it appears as a luminous and serene vision of a woman

surrounded by overflowing blossoms. This is due to the gentle pastel tones, billowing drapery, and an atmosphere of softness and perpetual spring. However, when considering the Greek myth behind Flora, known as Chloris, it introduces an essential perspective for interpreting Ricci’s composition.

The myth of Flora and her origins is described in Ovid’s Fasti. Chloris, who is originally a

nymph, is described to encounter Zephyrus, the god of the West Wind, who “seized [her] and made [her] his bride” before granting her authority over flowers (Ovid, Fasti 5.195–214). After this encounter, she becomes Flora, the goddess responsible for blooming plants, grassy fields, and the seasonal renewal of spring (Fasti 5.229–260). Ovid emphasizes her power to infuse the natural world with new life.

The reflection of these specific classical traits is seen in Ricci’s painting through the portrayal of Flora, where she is surrounded by emerging flowers that blossom simply by her touch. Her relaxed posture and luminous depiction align with the portrayal of her role as a nature goddess. The putti in the painting can be seen as helpers in the divine task, as they also represent the spreading of springtime’s embrace. The frolicking gestures of the putti represent the mythic idea of Flora’s realm being joyful, fertile, and ever-blooming (Theoi Project 2025). Furthermore, the symbolism in this work focuses on fertility, renewal, and the cycle of rebirth in nature. Since Flora governs the change from winter to spring, she represents the beauty of the world blooming and the beauty of nature’s growth. Ricci’s use of soft lighting and delicate colors enhances this symbolism, which leads to the creation of an atmosphere that feels eternal and frozen in time as spring arrives.

However, there are differences between this work and traditional portrayals of Baroque subjects. Ricci does this by avoiding the dramatic interpretation of Chloris’s transformation by Zephyrus. Instead, he represents a more serene interpretation of the myth. Ovid’s text has a darker undertone with their encounter, whereas Ricci’s work is from the perspective of the aftermath, with the beauty, growth, and abundance of life that is brought by Flora into the world. This fits with the era’s Rococo style, which preferred softer and more decorative scenes rather than more dramatic and darker themes. Thus, Sebastiano Ricci’s Flora is both a classical mythological representation and glorification ofthe goddess’s symbolic associations with beauty, life, and the natural world in perpetual bloom.

VII. Bibliography

Primary Source

Ovid. Fasti. Translated by James G. Frazer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931.

Secondary Sources

Blanton Museum of Art. European Paintings Collection Overview. Austin: Blanton Museum

Publications, 2020.

Bowron, Edgar Peters. European Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1994.

Royal Academy of Arts. “Sebastiano Ricci.” Accessed November 17, 2025.

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/sebastiano-ricci.

Theoi Project. “Flora / Chloris.” Accessed November 2025. https://www.theoi.com.

Written by Eshanni Sathishkumar

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called  Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

Theogony. If you need a smile and a laugh, or a quick summary of an ancient epic poem, please have a look at the link to Epic Mythomemologies on the website.

Theogony. If you need a smile and a laugh, or a quick summary of an ancient epic poem, please have a look at the link to Epic Mythomemologies on the website.

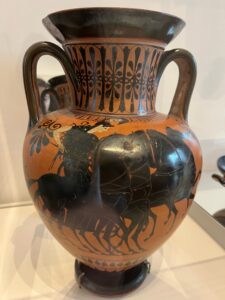

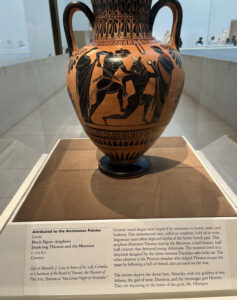

Black figure image of Theseus and the Minotaur on a Amphora dating to c. 520 BC

Black figure image of Theseus and the Minotaur on a Amphora dating to c. 520 BC