Artist: While listed as ‘anonymous,’ the time period from which this oinochoe was created allows us to imagine the techniques and styles used by the artist. A Greek poem, most likely composed in 6th century Athens, gives an amazing visual for pottery making during this time period:

If you pay me potters, I will sing:

Come here, Athena, and hold your hand over the kiln.

May the cups and bowls all turn out a good black,

May they be well fired, and fetch the price asked…

But if you turn shameless and deceitful,

Then I will summon the ravagers of kilns…

Stamp on the stoking tunnel and chambers, and may the whole kiln

Be thrown into confusion, while the potters cry aloud.

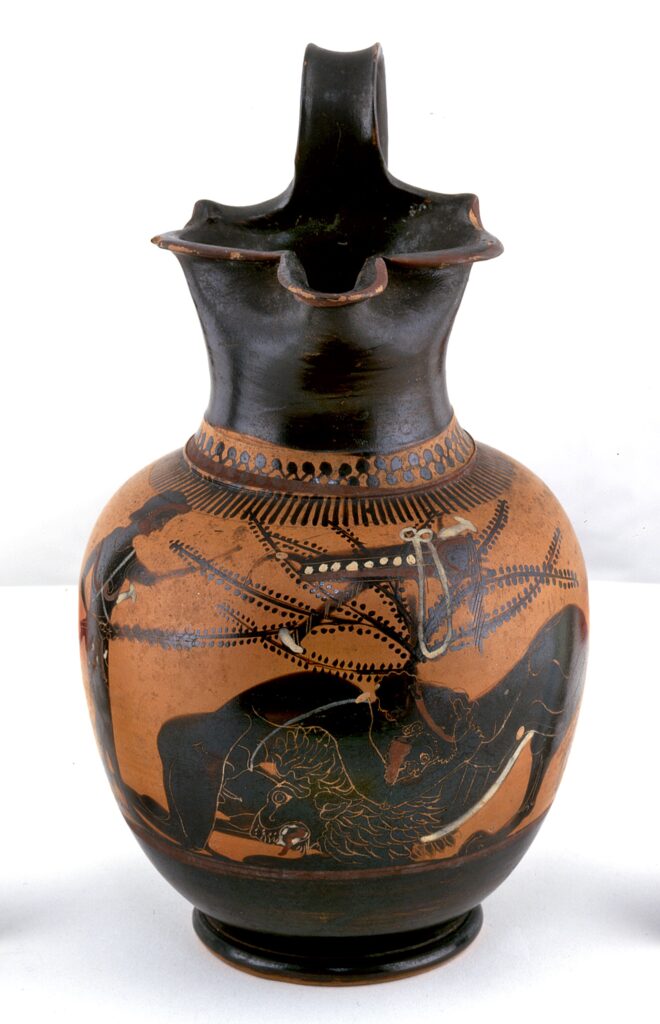

Great care was put into building the kiln, and pottery was seen as quite valuable. Black-figure vase painting was the earlier style utilized by Greek artists, as the materials were cheaper, but red-figure would soon take over. Many Attic vases show lighter painted lines that are raised from the surface, lines which added contour for clothing and anatomy. Instances of this technique can be seen in this oinochoe, with Heracles’ weapons in the tree and in the anatomy of the figures. It is also evident from this piece that the artist was skilled in their work, as the black gloss appears opaque and not a reddish-brown (Sparkes, Greek Pottery: An Introduction, 20-22).

Date: 550-500 BCE

Location: Blanton Museum of Art

Acquisition: This piece was brought to UT Austin by the Archer M. Huntington Museum Fund and the James R. Dougherty, Jr. Foundation in 1980. Archer Huntington dedicated his life to creating one of the world’s largest collections of Hispanic art and literature while the James R. Dougherty Jr. Foundation focused on creating collections of contemporary American and Texan art. This oinochoe from Attic Greece demonstrates a historical marker for pottery that adds to the timeline of techniques and styles used by artists.

Description: Athenian black-figure painting on an oinochoe (13.9 cm (5 1/2 in.) that depicts Heracles’ first labor: the Nemean Labor. A defining theme in the artwork of the demigod, Heracles, is that of his twelve labors.

Born from the affair of Zeus and Alkmene, the myth of Heracles finds its genesis in his pathos driven by the anger of Hera. Such is where we get his namesake, “Fame from Hera.” Driven by jealousy and hatred, Hera cursed Heracles with madness, causing him the kill his wife, Megara, and his children. To atone for his wrongdoings, Eurystheus, ruler of all the Argolid, instructed Heracles to complete a series of Labors that would prove his strength and virtue (Buxton, The Complete World of Greek Mythology, 114-115).

The first labor, the Nemean Lion, hinted at the strength and cleverness of the Greek hero Heracles. On the oinochoe, weapons are depicted hanging from the tree, reminding the viewer that Heracles fought the Nemean lion with his bare hands. In On Heracles, written in the late 5h-early 4th c. BC, Herodorus attempts to rationalize the true meaning of the myth of Heracles through allegory. The lion is a noble animal, and with the skin of the Nemean lion wrapped around him, Heracles is noted as a noble hero. Herodorus also mentions Heracles’ iconic club as a symbol for philosophy (Herodorus, On Heracles, 14). This club is also depicted on the oinochoe, being held over the head of Heracles by his son Iolaos as a gesture of assistance.

An oinochoe is a vessel for wine, one which would’ve been used in a Greek symposium. These ‘drinking parties’ were dominated by the men of the society, and it is where we often see instances of pederasty. The relationship between the Greek eromenos and erastes was often used for mentorship and even political preferment (Ludwig, Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory, 30). The depiction of Heracles on the oinochoe could therefore reinstate the power of men in the society and the importance of mentorship and filial piety seen in the inclusion of Iolaos in the piece. The defeat of the Nemean Lion is the pinnacle of male strength in the perspective of Ancient Greece, and the use of such a scene with the respect to the Greek symposium emphasizes the importance of patriarchy in the Greek society.

Sources:

Buxton, R. G. A. The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Ludwig, Paul W. Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Sparkes, Brian A. Greek Pottery: An Introduction. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1991.

Trzaskoma, Stephen, R. Scott Smith, Stephen Brunet, and Thomas G. Palaima. Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2004