Citation

Örnek, Cangül, and Çagdas Üngör. Turkey in the Cold War: Ideology and Culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Internet resource.

Contents

Essays collection

Introduction: Turkey’s Cold War: Global Influences, Local Manifestations

Örnek, Cangül (et al.)

Pages 1-18

- Cold War in the Pulpit: The Presidency of Religious Affairs and Sermons during the Time of Anarchy and Communist Threat

- Kenar, Ceren (et al.)

- Pages 21-46

- China and Turkish Public Opinion during the Cold War: The Case of Cultural Revolution (1966–69)

- Üngör, Çağdaş

- Pages 47-66

- Cultural Cold War at the Izmir International Fair: 1950s–60s

- Durgun, Sezgi

- Pages 67-86

- Engagement of a Communist Intellectual in the Cold War Ideological Struggle: Nâzım Hikmet’s 1951 Bulgaria Visit

- Somel, Gözde (et al.)

- Pages 87-105

- Issues of Ideology and Identity in Turkish Literature during the Cold War

- Günay-Erkol, Çimen

- Pages 109-129

- The Populist Effect’: Promotion and Reception of American Literature in Turkey in the 1950s

- Örnek, Cangül

- Pages 130-157

- From Battlefields to Football Fields: Turkish Sports Diplomacy in the Post-Second World War Period

- Irak, Dağhan

- Pages 158-173

- Land-Grant Education in Turkey: Atatürk University and American Technical Assistance, 1954–68

- Garlitz, Richard

- Pages 177-197

- Negotiating an Institutional Framework for Turkey’s Marshall Plan: The Conditions and Limits of Power Inequalities

- Keskin-Kozat, Burçak

- Pages 198-218

Author

Context

This volume examines the cultural and ideological dimensions of the Cold War in Turkey. Departing from the conventional focus on diplomacy and military, the collection focuses on Cold War’s impact on Turkish society and intellectuals. It includes chapters on media and propaganda, literature, sports, as well as foreign aid and assistance.

Thesis

Methodology

Key Terms

Criticisms and Questions

Notes

Introduction:

Although turkey is Center Stage with Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan it is completely neglected in most literature.

– Facebook aims to address this important Gap by bringing the local ramifications of the Cold War ideoogical struggle to Global scholarly attention.

-What were the manifestations of the major Cold War ideological divisions in the Turkish context>? What was the role of official institutions and pro-establishment intellectuals in disseminating pro-western and anti communist ideas? how did Turkish officials intellectuals and dissidents respond to American influence in the social economic and cultural fields?

– young Turkish Republic was friendly with the Soviet Union because it received political and material support during the war of independence. friendly relations throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Maine collaboration was economic planning and industrialization.

– deterioration of relationship during the second World War when Turkish men of letters immigrated from the Soviet Union and sympathized with Nazi Germany. after the war when atrocities were revealed these Pro Turkish intellectuals would be prosecuted.

– Soviet demands for the Bosphorus shipping channel and Eastern Anatolia would push turkey away from it.

– the Turkish Confederation of revolutionary trade unions founded in 1967 fiercely challenged the pro-government labor Confederation that had advocated american-style free unionism since the early 1950s.

– in the liberal atmosphere of the 1960s translations of the previously banned marxist Classics became popular and a discussion over Soviet realism took place.

– after 1980 the Turkish Islamic synthesis came to dominate the educational curriculum as well as other aspects of social life.

Chapter 2 : China and Turkish public opinion during the Cold War : the case of a cultural revolution

– during the cultural revolution turkey had limited information about China because of linguistic and academic expertise.

– there were two main images that opposed one another about Maoist China: The mainstream media was preoccupied with order and stability and was upset with the violence leftists on the other hand we’re greatly inspired

-Overall it helped to deepen the debate over the Cold War in Turkey.

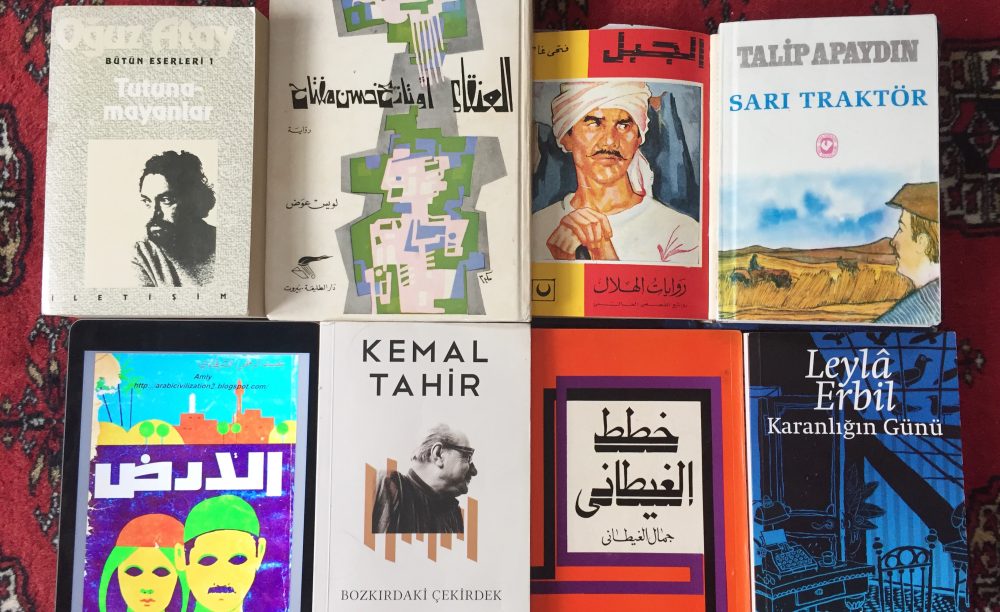

Chapter 5: Issues of ideology and identity in Turkish literature during the Cold War

-The impact of the 1930s First Congress of Soviet Writers had an immediate impact on Turkey. Karsosmanoglu went to it.

-Nazim Hikmet was a huge influence on the left cultural scence until the 50s.

-1940s poets under Hikmets influence: Hasan İzzettin Dinamo, A. Kadir, Enver Gökçe, Arif Damar, Ahmed Arif: unıted in their exploration of war and militarism, class struggles, and the explotation of workers. Can Yucel published discorse on anarchism and eroticism in the Marxist vein.

-Parralel to the rise of the socialist realist poets with less political messages but trying to mimetically represent all levels of society: Reşat Enis Aygen, Bekir Sıtkı Kunt, Kenan Hulusi Koray, Mehmet Seyda. And stories of ordinary people in life: Sait Faik and Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı

-most prominent anti soviet writer was Nihal Atsız

– village themese by the three kemals: Tahir focused on the sexuality and corruption which overturned fetisization of anatolian aggrandizement. Degeneration and misery.

-Orhan Kemal’s baba evi is an allegory for the instability of the turkish republic, identity search.

-Literary left tradition opposed to hegemonic politics: Aziz Nesin, Sabahattin Ali, Rifat Ilgaz, Vedat Turkali, and Yasar Kemal.

-Ince Memed carefully explores utopian revolutionism and the hero who is fallable.

-Kisakurek became anti-communist who was also critical of westernization.

-Some of the best socialis rrealist writers for village novels: Talip Apaydin, Kemal BIlbasar, Fakir Baykurt, Dursun Akcam. Many suffer from dramatic hero imbalance.

-Next generation of socialist realist poets: Hasan Huseyin, Sukran Kurdakul, Ataol Behramoglu, Gulten AKin. Behramoglu close to soviets and spent two years in Moscow.

-Kurtlar Sofrasi – discusses the rise of new classes in Turkey in parallel to Mahmud’s struggle between personal romance and sense of duty to society.

-Devlet ana focuses on ottoman beginnings as pseudo-socialist state and social structure.

-Generation of 1950 was a counter-current in Turkey lacking domineering socialist-realist lit, city origin, aienation of intellectuals and growing distrust of people: Vusat O Bener, Demir Ozlu, Ferit Edgu, Orhan Duru, Yusuf Atilgan, Bilge Karasu, Tahsin Yucel, began writing between 1950-60.

-Tutunamayanlar the identity conflicts of a petty-bourgeois intelelctual like the gen of 1950.

-Yasar Kemal – Yusufcuk Yusuf (1975) the tension between established and contemporary landowners, making the transformaiton from aga to bey a metaphor of the transformation from fuedalism to premature capitalism.

“Organic Intellectuals of Urban Politics? Turkish Urban Professionals as Political Agents, 1960-80.” – Bülent Batuman

Thesis:

The Urban masses were politicized in the 1960s and 1970s. Urban architects and planners played a big role as organic intellectuals. What were their counter-hegemonic potential?

Notes:

If the classes are not understood as preceding the domain of struggle but rather as being products of it, the intellectuals’ ‘organicity’ can be defined in relation to hegemonic struggle rather than the classes as pre-given elements of the struggle.5 In other words, organic intellectuals can be defined through their relation to the political struggle rather than the classes themselves

The seeking by urban professionals of a means of maintaining closer ties with the popular classes found an answer in ‘advo- cacy planning’, which is the third influential issue that emerged in the second half of the 1960s. Calling for the planners to become the voices of the disadvantaged social groups (Davidoff, 1965), the idea of advocacy plann- ing was enthusiastically embraced for a short period by the Turkish planners and archi- tects as well.

As the experience of urbanisation in Turkey took place parallel to the introduction of a multiparty regime, the process of squatt- ing had always been marked by electoral concerns. As a result, an important issue in the election campaigns —which was widely used by the right-wing governments exploiting the advantage of being in power—was the promis- ing of title deeds to the squatters

The 1971 intervention brought out two unintentional consequences that disrupted this clientelistic structure and eventually paved the way for the radicalisation of squatters during the 1970s. The first of these was the violence generated by the military regime, which was experienced by the squatters in the form of demolitions. The demolitions became a significant aspect of the military regime determinedto‘restoreorder’inthecities.Yet, they served to increase the politicisation of the violence the squatters faced occasionally and also established a connection between democratic demands and resistance to the demolitions.14 The second outcome was even more incidental. The military administration closed down all the beautification societies together with other civil organisations and including some of the political partie

When the societies were reopened after three years, they were appropriated and politicised by the younger generation of squatters as a means to organise against such mafia groups (Heper, 1982). Hence, the period under the military regime set the stage for the un- foreseen turn of the squatters to the left. This shift occurred in terms of both their voting left in the 1973 elections and the gradual establishment of links between the squatters and the radical left.

26. State and Class in Turkey – Cağlar Keyder

Citation

Keyder, Çağlar. State and Class in Turkey: A Study in Capitalist Development. London u.a: Verso, 1987. Print.

Contents

1) Before Capitalist Incorporation

2) The Process of Peripheralisation

3) The Young Turk Restoration

4) Looking for the Missing Bourgeoisie

5) State and Capital

6) Populism and Democracy

7) The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialisation

8) Crisis Dynamics

9) The Impossible Rise of Bourgeois Ideology

10) Conclusion as Epilogue

Author

History Professor

Context

Turkish history is so distorted by the lionization of Ataturk, by the ideology of nationalism, that it’s hard to see the very normal and very decisive class conditions that are at play underneath them.

Thesis

A bourgeoisie was missing for much of Turkish history due to the history of small-holding peasantry, the power of the bureaucracy, and the expulsion of the fledging christian bourgeoisie.

Methodology

Key Terms

Criticisms and Questions

Class interests in the style of the 18th Brumaire become clear and overwhelming once you can take a step back. Maybe the anxiety over the analytical explanatory power of class in comparison with race/gender is of a different scale.

Notes

1) Before Capitalist Incorporation

-Ottoman order was constructed onto Byzantine order, not feudal. small peasantry stayed intact. no slavery or serfdom.

-Byzantine land code: protect peasants’ landed and other property, use village as communal unit for taxation.

-Ottoman centralisation 3 centuries later restored basic contours of Land Code.

-later half of 19th century restoration of agrarian structure.

-Dispersed agricultural producers required parallel dispersion of mercantile activity.

2) The Process of Peripheralisation

-Tanzimat socialization took small holding peasants as an ideal.

-No arisotracy, everything based on bureaucratic position.

-Civil bureaucracy differentiated itself from religious officials in 18th century.

-Trade convention with England 1838 started Ottoman financial integreation with European system.

– Bureaucracy threatened by growth of bourgeoisie as christian intermediary class.

-Bureaucracy emerged as paternalistic defender of a normative social order while the public debt administration represented the rule of the market.

-important to distinguish between merchant capital (local labour for commoddities) and productive capital (purely monetary)

-Proletarianisation was unlikely because defended by bureaucracy, reluctance to sell land ownership to foreigners, and small holdings.

-No disposessed peasantry as a free proletariat.

-Foreign capital remained limited to trade-related activities.

3) The Young Turk Restoration

-Bureaucrats’ how life depended on state, so were all completely wrapped up in state-centered perspective.

-Young Turks could take over state mechanism but did not have a manufacturing bourgeoisie whose interests could be served through the construction of a national economy.

-When the CUP took power they had not discovered the social group whose interests would provide an orientation for future policies. They tried to safeguard the centrality of state power, it was this, not ideological consistency, which informed policies.

-CUP ascension occasioned blossoming of christian art and culture. But bourgeois freedoms was not assimilated by perspectives of the ruling class in a state-centric empire.

-Started to distrust christians especially after the Balkan wars. This is what left towards policy of Turkish nationalism.

-Bureaucracy established itself on top during WWI. Could have have been a class controlling the productive structure, but class struggle with the bourgeoisie was displaced ideologically to ethnic and religious conflict.

-Settled on Muslim merchants as class to back.

-Christian minorities eliminated by 1924, 90% of the pre-war bourgeoisie.

4) Looking for the Missing Bourgeoisie

-Islamic Ottomanism out after ‘Arab betrayal’, Turks aligned with Soviets, Anatolia became ideoligcal focus, attack by Greeks helped to unify the military-bureaucratic class.

-Power shifted from Istanbul to Ankara after parlimentary elections.

-Any changes would have to be around edges of relationship between bureaucracy and independent peasantry.

-no capitalism in agriculture, christian merchants refused Ottoman state

5) State and Capital

6) Populism and Democracy

7) The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialisation

8) Crisis Dynamics

9) The Impossible Rise of Bourgeois Ideology

10) Conclusion as Epilogue