This book had all of the elements to make it an all-time favorite for me. Especially the common refrain about it being the spiritual successor to Yaşar Kemal. And so I was very disappointed when, around 300 pages in, I realized that the novel is quite tedious.

I think for me the main reason is that the parallels with an ecologically-focused epic Yaşar Kemal is that Duman’s actually has very little to say about nature. Sure, there are animals. And we get a chilly passage of ekphrasis in almost every chapter. But the understanding and description of nature is nowhere near the intimacy of, say, Demirciler Çarşısı Cinayeti. I can’t remember Duman naming one actual tree or plant species throughout the entire novel. We get far more descriptions of icicles and wind which are, let’s be clear, meteorological more than ecological elements.

I’m also a stickler for animal narratology, and there are so many sophisticated and novel ways that it is being experimented with in contemporary fiction (see https://academic.oup.com/book/11415). But this novel, instead, uses a muddled mythological elevation of Sus Barbatus to lend us some insight into its being with saying anything of substance about its species being (yes, I think this term is still analytically relevant, but almost exclusively when speaking about actual animals). Sus Barbatus’ consciousness exists even after Kenan kills it: why? What’s the point? What does that tell us about the relationship between humans and non-humans. I didn’t take a single thing from the drawn-out drama of pig consciousness, nary a clunky metaphor.

Many people also comment about the short chapter length, and the novel’s overall length. I don’t have a problem with either by themselves, but again, what purpose did they serve? Oftentimes I felt like having the narrative interrupted every three pages made it so we had to continually be reestablishing the scene, often times by describing the same things over and over again. Tedious.

Perhaps all of these loose narratological threads are pulled together brilliantly if only I were to commit to reading the other two volumes. That is not a benefit of the doubt I am willing to lend after what I’ve read so far.

My First Day in Heaven Was, Honestly, Less Than Ideal

My First Day in Heaven Was, Honestly, Less Than Ideal

My First Day in Heaven Was, Honestly, Less Than Ideal

By Sezen Ünlüönen

translated by Matthew Chovanec

My First Day in Heaven was, honestly, less than ideal. By the time the trumpet had been blown on the day of judgment, and all living things had been gathered together in the great summoning, and we sat there endlessly waiting for them to bring the book of deeds, I was bored out of my mind. Next to me, this guy named Vecdi Efendi (not Mr. Vecdi, Vecdi Efendi he said scolding me) was reciting verses from Surah Ibrahim, from Surah Kaf, crying out “Oh Prophet of God! intercede on my behalf,” muttering things in Arabic. God forgive me for saying this, but he was like a high school student trying to memorize formulas ten minutes before an exam. What a kiss-ass! (and would you look at me, he’s got me started with all this God forgive me crap, his groveling must be contagious.)

And besides that, seeing that the whole process from start to finish was happening just like Muslims said it would, that the Gates of Heaven were opened first and foremost to believers, I would be lying if I said I wasn’t a little bummed about that.

Look, don’t be fooled by my nonchalant attitude, it was nerve wracking having to cross over the Sirat bridge, riding slowly on the back of those rams my grandma had sacrificed on holy days. I quickly recited three obligatory “Qul-hu” and one “al-Hamdu lilah” prayer that I still remember from childhood, and once I had made it over to the other side to heaven I let out a huge sigh of relief. It seemed as though our Lord who created the heaven and the earth wasn’t going to punish those of his servants who’d drank two glasses of rakı, or going to be looking into which kind of animal meat they had eaten; apparently he was instead judging people by the goodness of their hearts and the purity of their conscience; it seemed that a heaven founded on such rational principles might just have space for such militant atheists as me.

A staff member was reading names off of the list in his hand in front of the gates. When someone’s name was called they would follow a person wearing a red t-shirt to where they’d be staying. The staff member was pretty bad at it, reading the slightly unfamiliar names like Kurkaskov, Kursakov, Korsakakov however he thought they should be pronounced. We had been told to wait quietly, you know since the topic at hand was the fate of our eternal afterlives, but everyone just kept talking and yelling, once in a while someone would try to make a scene and lose it and shout out “Allah!” and then fall down fainting. After a short while this skinny little boy started dragging out a microphone with a long cable on the ground, weaving in between everyone’s legs, like he was an unenthusiastic snake charmer carrying around a dead snake, and then handed it to the staff member. As soon as the staff member had taken the microphone in his hand, a deafening screech rang out. Some hysterical people, thinking that the trumpets of heaven had blown anew, started stammering “God’s Hellfire!” and then fainted again. Seeing that the microphone wasn’t working out, the inaudible staff member began reading the list again with his bare voice. The people of heaven, worriedly thinking “what if my name is called and I miss it” kept trying to elbow, step on, and shove past each other. Then some of them, God knows where from, started eating spoonfuls of slushie. “Where did you get that from? “Why won’t you share it with others?”? “What makes you think you deserve that?” “Hey auntie, my boy’s miserable in this heat, can he get a spoonful?” “Umm I don’t know, is he clean or does he have germs? If you had deserved one on earth then you would have been given a slushie too,” they said, pushing back and forth. You know, even when they get to heaven some people just don’t have a clue how to act, it’s like they’ve never heard of manners or etiquette.

Anyways, after all the arguing and pushing was over, they set us up in some bungalow-like accommodations, the one I was staying in was decorated in a minimalist Scandinavian style, which I was happy with, when it came to interior design I had always favored simplicity, but supposedly anyone who was unhappy with their accommodations could speak with management and have the assigned furniture switched out.

I learned that from the staff member in the red t-shirt who showed up when I pressed the service button next to the door of the bungalow. Now that I was moved in, I thought I’d celebrate my first day in heaven by asking for a Mai Tai with extra rum, but it took fifteen minutes for the drink to come. I mean if this was what service was going to be like in heaven… the boy waiting on me looked Syrian, it was sad to see we were up to our ears in them here too. I had hoped it would be one of those long-legged, big breasted, bikini-clad—whoa now, bikini? This was heaven wasn’t it— nude blonde who served me. I’ll speak to management about that as soon as possible.

Speaking of blondes, when I asked Kerim (that’s the name of the boy waiting on me) he told me that Huris and Ghilman were real, but that you had to go and sign up for them on a list. With a devout look in his eyes he recited the Quranic verse “Indeed, we will perfectly create their mates, making them virgins, loving and equal in age.” It was going to be a real drag if heaven was going to be filled with all of this sappy religious talk.

When he left I thought more about the whole “equal in age” thing. As far as I was concerned, at thirty three I was in the spring of my youth, at the peak of my strength and virility, but thirty three years old for a woman, that’s a lot. Couldn’t we get someone a little more spry? I thought maybe around ten or fifteen Thai girls who are on the younger side would be a good start but hopefully they won’t give me a hard time about it. You know, like I said, my first day in heaven was, honestly, less than ideal, but it’s still just the beginning. We’ll see what tomorrow brings.

*

This morning when I woke up I decided to go on a 5k run like I always used to before. But then I wondered if you could eat whatever you wanted in heaven and be as fit as you’d like without having to do any exercise. My hand went reflexively for my phone. But then I remembered I didn’t have a phone. I could probably just ask Kerim, but this early in the morning I didn’t really want to have to look at his creepy little face, plus, instead of having to deal with Kerim I’d much prefer to just have a phone. You know, it’s better when everyone has one, you can goof off and play games once in a while, keep in touch with friends and family easily.

Speaking of friends and family, I realized I hadn’t thought about my parents, or that asshole Berk, or about my first wife or Elvin or about Özge since I had gotten here. I wondered if they had been able to get into heaven? Gülgün, that battle-axe, she would have had a hard time, Berk wasn’t of help even to himself in life, but my mom, for example, she had never wished anyone any harm. If being a dumb was an obstacle I’d think differently about Özge of course, but when I thought about the average person around here, I had no doubt that Özge would fit right in. On the other hand though, I had no desire to see Özge here without her face-lift, her hair done up, or without her laser hair removal. I doubt I’d even recognize her, hahaha.

I looked through the cupboards, I found coffee, there was a French press but no espresso machine, no way to make a latte or a cappuccino. I made coffee and went outside. In the garden of the bungalow next to me there was an aging woman doing yoga. I gave a little wave, and she gave me a slight nod. For a second I wondered about how the Galatasaray-Fenerbahçe match had gone, but then about how now that we were in heaven, did they have dream teams like with Maradona and Pele on them, and if we could watch them play. I’ll have to give that question to Kerim. Doing everything by myself like this is a joke, and against the spirit of heaven, as soon as possible I’ll ask for a secretary. That got me thinking about the whole Huri thing again, so I decided to go right away and sign up.

It took twenty five minutes to walk to the “Human Resources Office.” what kind of heaven is this, I don’t get it, what the hell was I doing walking down the road dripping in sweat, was this what I had been seen worthy of heaven for? Half joking, I said to Kerim, who had come along, “ how about you carry me on your back,” he gave me such a dirty look you’d think I was cursing out his mother, but it’s cool, it was some good cardio huffing it and then I made it to the office. The whole place was a mess, the service counter machine was broken, lines everywhere, if you asked what people were waiting for half of the morons waiting there had no idea. A staff member in a red t-shirt who saw me looking around annoyedly asked, “ are you an acquaintance of Berk Tokgöz?” Thinking about what mess he must have gotten himself into I thought about denying it, but then changed my mind and said “yes, I’m his older brother.” Then he told me “you don’t need to wait here,” and took me through the door marked “personnel only.” There, without having to wait in any line, and while even getting to sip a Turkish coffee, I got to state my request for a “blonde, 18 year old, C cup, D cup is fine, but no B cup.”

Leaving I felt super hungry, I found a Pide place and sat down. I asked for two with chopped beef along with one with Tahini but the waiter, covered in sweat, told me “Tahini is too much work, we can’t keep up, it’s just the two of us running around doing everything.” Here I am in heaven in this rancid smelling place, talking to a pimple-faced kid, not even able to enjoy one single pide, waiting in a bunch of stupid lines, having to walk twenty five minutes just for two Huris, I was pissed. Without saying anything I left and went home.

There were a couple people having a conversation in the garden. I don’t normally like to make small talk with random people, but with nothing else to do, I went up to them. Vecdi Efendi, you know the one from the day of judgment, along with the old artificially tanned woman I had seen doing yoga and a couple other people were excitedly talking to each other. The old lady turned to me and said “ you, have you ever made an artichoke balm?” As I looked at her blankly she went on “Chakra meditation? Aura cleansing? A Silent retreat?” Vecdi Efendi replied “madame, madame, what has that to do with anything? I saw this gentleman crossing the bridge of Surat on the back of a ram. It is clear to me that he, like me, did not falter in his duties to prayer, sacrifice, or worship.”

“Did you go on Hajj?”

“Isn’t Allah already aware that for extenuating circumstances I was unable to go.”

“I fed orphans on a lot of holidays mainly, that’s the main reason I think.”

Someone else mockingly said: “Well now that you’ve made it here to heaven, why are you still fussing about the reasons why, have some whisky, some cocaine, go on and live a little.”

Wait, did they really have cocaine in heaven? I pushed the button a few times to summon that idiot Kerim who was nowhere to be found. It took him an hour to get there. When he finally showed up, I was so angry I had forgotten all about the cocaine. I chewed him out “where have you been this whole time son?”

“I have three other heaven-residents that I’m responsible for, I can’t keep up,” he said groveling. This kid had an air of subtle disrespect to him, but I had no idea how I was going to discipline him. I forgot about it and sent him off saying “go find some cocaine.” Naturally, saying cocaine immediately made me think of Berk. How was it that that jackass ended up being a person with influence in heaven? It would stand to reason that in a place where he had any pull I should have ten times as much, but had he gotten here before me? Or did they not know exactly who I was? If they did know, would I be stuck here in this shitty bungalow with that dumbass Kerim? Right?! Tomorrow I’ll say something, they’ll see to putting me up in a villa on the Bosphorus, then I’ll begin to really enjoy life, or should I say enjoy heaven.

*

Dear journal, I am writing these lines from a villa on the Bosphorus. Normally I would be above this dear journal business, but boredom has driven me to take up the hobby of a high school girl. I thought about looking up Özge so that we could hook up until the Huris got here, but once they arrived it would have been hard to get rid of her. I can’t take any more of her fits of jealousy, her freakouts, her moodiness.

The villa has already lost its appeal. To get everyone a villa who wants one they’ve had to extend the Bosphorus out for kilometers and kilometers, to get from one side to the other it’s not thirty kilometers, it goes on forever. What kind of Bosphorus is that?

I called Kerim, and I had him bring me a shrimp cocktail and some appetizers. He set out an elaborate spread, and I asked him about the Huris while getting hammered. He said it could take up to six months, maybe if I called up Berk and asked things could be sped up.

When I said alright then well then where is that son of a bitch Berk he winced like I had just cursed the prophet, then, sounding all enigmatic, he said “ I am unable to know.” Here I am trying to relax, looking out over the Bosphorus and this dumbass is still standing there squirming like he’s in pain. Finally I couldn’t take it anymore so I asked him what he wanted, and after playing coy for an hour he finally spilled it, could he have a taste of the shrimp cocktail?

I was fed up, and had completely lost my appetite. I begrudgingly pushed him the plate. It’s always like this, people are always acting friendly and polite, pretending to be courteous, but then before you know it they’re badgering you to death.

I thought to myself: tomorrow I’ll find Berk and ask him where he got all this authority from, that’s what I’d like to know, and also speed up this whole Huri business, and also that I’ll also take one of those latest models of Italian sports cars thank you very much. Like nobody at the club could touch me when it came to driving, the people here, they’ll see, I’ll show them just how a car is driven.

*

I got a car but it’s second hand.

Kötü Kalp by Aslı Tohumcu

Depictions of violence against women is so terrible that in fiction it often requires some sort of conceit to make it bearable. I think of, for example, of Fernanda Melchor’s use of gothic horror and skaz in her novels Hurricane Season and Paradais. Likewise, in Kötü Kalp, Aslı Tohumcu frames her gruesome short stories about pedophiles and womanizers and men abusing their power within the plot of a detective novel. But the quality of a novel that uses this strategy shouldn’t be judged merely by how successfully it is able to sustain a confrontation with violence, but by how the adopted genre form is, in turn, changed by its content.

Take, for example, Frankenstein by Baghdad by the Iraqi writer Ahmed Saadawi. Not only does he cleverly use the famous horror story of Frankenstein to depict the horrors of the violence in the wake of the American invasion in 2003, but in the process makes Mary Shelley’s famous monster an allegory for the absurd, undying drives of sectarian violence.

Unfortunately, while Tohumcu adds a detective story plot to her depictions of violence against women, her novel isn’t carried beyond the simple addition of genre tropes, and doesn’t even make use of a twist or big-reveal (the genres greatest tools!) to say something beyond the simple terrible fact of violence. Simply reversing the usual victim and perpetrator isn’t enough for me!

رواية بيئية بلا تاريخ ولا سياسة ولابيئة

” لا نحتاج إلى الكثير من الفلسفة لنقول إن لا حياة دون ماء، لكن استحضاره روائيا يعد أحد الأوجه الأصيلة للبيئة العربية، فلا يمكن أن تقرأ عملا أدبيا من الخليج تحديدا دون أن تستشعر وجود الماء، وكأنه صفة لصيقة بالأدب الخليجي. وهذا ما يؤكد أن الرواية الأصيلة هي تلك التي تستنطق بيئتها روائيا بما يتناسب وما يريد الأدب قوله”

في مراجعتها للرواية “تغريبة القافر” تدعي سارة سليم ان ” الرواية الأصيلة هي تلك التي تستنطق بيئتها روائيا.” ولكن اذا قامت هذه الرواية باستنطاق فكان برفق شديد. تلهم شأن الأفلاج في عمان عدد لا يحصى من التساؤلات عن التاريخ والسياسة والبيئة ولكن لا تطرح الرواية اي منها بل تلجأ الى وصف العالم الطبيعي لا يتجاوز عمق الأدب الرعوي التافه.

مع اننا لا نعرف بدقة أصل نظام الافلاج العمانية يمكن الاشارة على أدلة مثيرة بالاهتمام من مجال علم الآثار تدعى انها تسبق وصول العرب الى جبال الحجر. من كانت هذه الامبراطوريات العتيقة ذات القادرة الادارية اللازمة لانشاء مثل هذه القنوات، وكيف تبني وصان هؤلاء المهاجرون العرب هذا النظام الزراعي المتطور بدون المعرفة التي تجيء بخبرة بنائها، وهل يستوعب الذكرى الجماعي تراث العجائب مجهول الأصول، سواء بعزوها إلى عملاق ملك سليمان او الاعتراف بلغزها باستخدام الصفة بأنها مجرد “شيء مبهم”؟ يشبه هذا الرابط بين تراث الحضارات العتيقة والريف المعاصر العلاقة بين الماضي والحاضر في رواية “الجبل” بفتحي غانم التي تسرد حكاية سكان قرية في الريف المصري يزرقون من نبش الآثار الفرعونية وبيعها للأجانب بدون ان يفهمون قيمتها التراثية ومحاولات الحكومة المعاصرة لايقافهم وتهجيرهم لقرية “نموذجي” لكي يساهموا في النشاط الاقتصادي الناتج. ولكن لا تتناول رواية “تغريبة القافر” موضوع هذا الرابط إنما تبتكر حكاية ولد منعم عليه بمهارة شبه ساحرة تمكّنه اكتشاف منابع المياه الخفية في الجبال. بدلاً من “استنطاق” المجتمعات التقليدية وكيف تعتماد على التراث المبهم فيضرب الكاتب كليشيه ال”مختار” مثل ما نشاهد في حرب النجوم وهاري بوتر.

الزراعة في منطقة جبال الحجر التي تستفيد من الأفلاج هو مبنى على نظام الملك الجماعي الموروث من العصر الكلاسيمي، نظام يوفر مصدر ثامر للحكايات عن الحياة الاجتماعية. يمكن التخييل نسخة عمانية من رواية عبد الرحمان المنيف “التيه” تسرد حكاية مجتمع تقليدي يهدده فرض علاقات رأسمالية للملكية. ولكن بدلاً من هذا فالصراع الاجتماعي الرئيسي بالرواية يركز في نبذ الولد وتشكيك سكان القرية عنه بسبب مهارته الساحر ة في ايجاد المياه تحت الأرض. وبالاضافة الى ذلك يضيف الكاتب حبكة زوجية من أجل تزيين رواية رعوية بقليل من الغرام.

كل التغطية الصادرة من عمان تخبر ان يتوجه تراثها الثقافية الفريدة من نوعها ازمة وجودية بسبب الاسراف والتلوث واسلوب الاستهلاكية المعاصر غير المستدام. تصف مقالة محزنة للغاية كيف نظام الافلاج الذي قد استمر لمدة قرون الأن على حد الانهيار التام بسبب الضخ غير المنظم للمياه الذي يكاد استنفاد طبقات المياه الجوفية وبذلك جفاف الافلاج المنتظر. ولكن لا تتناول “تغريبة القافر” شأن السياسة ولا البيئة كما لا تتناول التاريخ. بدلاً من استخدام الرواية الرمزية لكي تعالج مأساة استغلال الإنسان للعالم الطبيعي الذي يزرقه، يقدم الكاتب في عرض ثالث من روايته تطور مفاجئ صعب التصديق حيث الماء هو تهديد حرفي.

سارة سليم على حق عندما تقول انه غير ممكن أن تقرأ عملا أدبيا من الخليج تحديدا دون أن تستشعر وجود الماء، وهذه الرواية ليست استثناء. بالصراحة تستشعر الماء خليجياً، يعني تتجنب القول بأي شيء تحليلي او نقدي بل تعوذ بالكليشيهات الرعوي المطمئنة وبساطة أخلاقية القصص الخرافية

https://www.alquds.co.uk/%D8%AA%D8%BA%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B1-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%B2%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7/

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Production_and_the_Exploitation_of_Resou/4WFqEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=oman+water+divining&pg=PA285&printsec=frontcover

https://e360.yale.edu/features/oasis_at_risk_omans_ancient_water_channels_are_drying_up

الخصوصية المُترجَمة

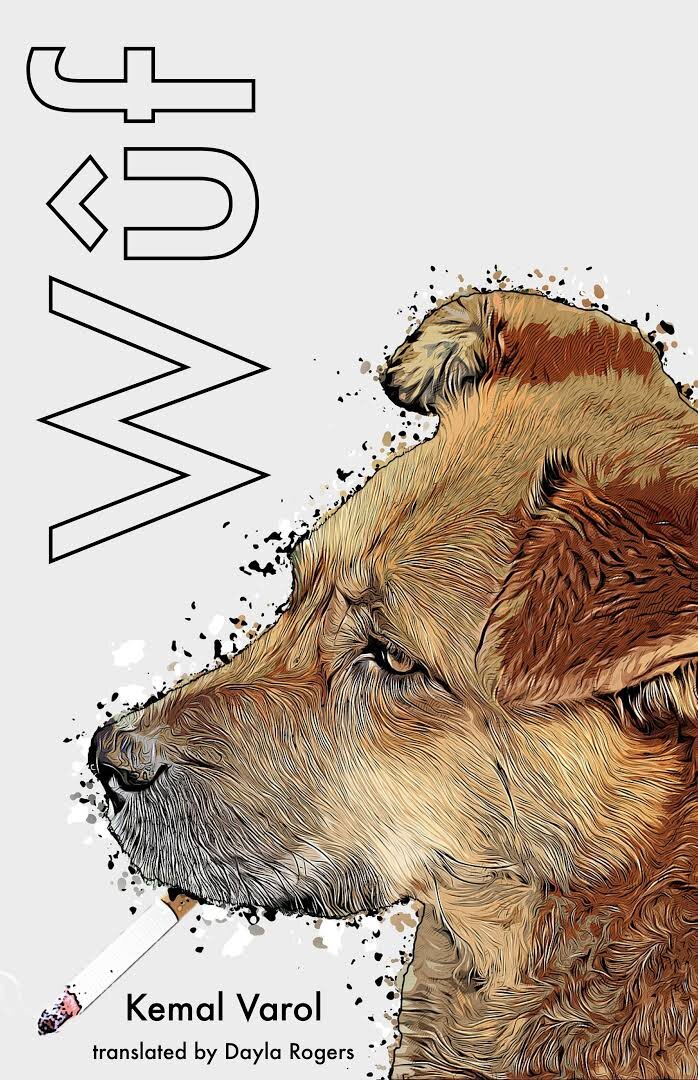

Review: Wûf by Kemal Varol

Do we really believe that the human imagination can sustain itself without being startled by other shapes of sentience?

-David Abram

There is a scene early on in Kemal Varol’s novel Wûf in which an old, injured dog gets the watchman at a kennel to give him a cigarette. The dog, nicknamed Grandad, had been brought in after being found blood-soaked and with his back legs amputated up in the mountains. His fur is matted and his belly is covered in stitches, and in place of his legs are two wheels, attached to each stump. Unable to directly speak a human language, he communicates through barking.

For the first time since the day he was brought to the shelter, Grandad let out a woof, not to frighten or threaten, just to communicate. But the watchman didn’t understand…

“You want bread?” he asked.

Grandad barked.

“Those wheels bothering you?”

Granddad barked even louder.

“You want food?”

The watchman finally catches on that it is might be the cigarette that Grandad is after, and asks him to bark three times if he’s right. Grandad does so, and so the watchman places a freshly lit cigarette into his saliva-coated mouth.

There is something off about the scene when you first read it, even despite the fact that we have already been introduced to a whole cast of speaking dogs at the kennel. Off because stories with talking animals, regardless of how whimsical, are still expected to set their own fantastical ground rules early on, and then stick to them lest the illusion gets its wires crossed. We’re willing to believe in the proverbs and poetry of Watership Down as long as its characters continue hopping around like rabbits. On the other hand, we can accept the fact of Roger being framed for murder and canoodling with Jessica Rabbit as long as he doesn’t try to hop around like one. But the talking dogs of Wûf seem to renegotiate their relationship with humans throughout the whole book. With their foul-mouthed vernacular and colorful nicknames—“forknose”, “Mikrob”, “Gunsmoke” —the dogs initially seem to share some sort of insular gang subculture, like a canine version of The Warriors. At other points, they seem fully integrated into the human world as working dogs, understanding not only that they are being trained but what they are being trained for. At some points, like in the cigarette scene, dogs can communicate with humans, and are apparently entire cognizant of the human world and its simple vices. At others, dogs and humans stare back at one another in incomprehension. The dogs of Wûf are fully capable of expressing the range of classic dramatic emotions, from jealousy to heartsickness, but still lick each other’s faces and shit on the ground.

This is especially true of the novel’s many tie-ins to the regional conflict taking place in the early 1990s in the south of Turkey where the book is set. The main character Mikasa (named for a type of Turkish soccer ball) is being trained by the Turkish military as a mine-sniffing dog, and the novel is full of references to political rallies, coups, and violent confrontations with guerillas. But never once in the original book is the word “Kurd” or “Kurdish” ever used. Instead, Mikasa and the other dogs refer to the conflict as one between Northerners and Southerners. The logos and flags of Kurdish parties are described by the dogs without a clear sense of their exact political meaning. The dogs know that the bombs they are sniffing out have been left by guerillas, but they don’t know exactly why. Strangely, at one point Mikasa even mentions that the papers declare the death of twelve of them, implying briefly that beyond their ability to speak, dogs in the universe of Wûf might be able to read.

Which would all be cause for worry if the novel was in fact written as a neat political allegory of the Kurdish conflict. We could then easily guess which role the oppressed and unheard animals were supposed to be playing. From what we know of Varol–whether his obscure poetry or his eschewal of declarative forms of politics– it seems out of character to be trying to write an Anatolian Animal Farm. Politics in the novel function as a backdrop; the rugged scenery of what is at its base a simple, tragic love story. And rugged is an understatement. In his quest to be joined with his love Melsa, the dog Mikasa is cursed, kicked, muzzled, starved, shot at, and blown up by mines. The details of Grandad’s injuries as he tries to heal are terrible and vivid.

His stump, which had dragged on the ground, slowly regained its range of motion until it finally pounded the dirt and twitched side to side. The stitches on his belly came out on their own, the cuts on his back scabbed over, and his bloodstained coat began to shine anew. The only thing left were the bandages on his legs. The harness always got in the way of his attempts to gnaw them off.

This description would be familiar to many in Turkey, who have themselves been witness to acts of cruelty and extermination carried the country’s large stray dog population. Varol’s hometown of Ergani, a city in the Diyarbakir province in the south, has seen its own stray dog problems along with political violence stemming from the Kurdish conflict. The media often has stories about dogs that have been poisoned en masse, CCTV footage of dogs being indiscriminately beaten, and conversations about how to forcibly remove them from the city. A July, 2019 report on NTV claimed that the forests around Istanbul are home to more than 8 thousand stray dogs that have been shipped out from the city center, showing surreal footage of them wandering around in large groups on a deserted rural road. One resident of a nearby village claims that the city is under attack every night by roving gangs of dogs, while another details the efforts taken to bring out leftover food to the dogs in the woods. These simultaneous reactions of dread and sympathy towards dogs is a feature of daily life. The lighthearted tribute to cats seen in the recent film Kedi could easily be remade as a tragedy called Köpek.

Which is to say, as a novel offering perspective on Turkey, it would be enough for Wûf to actually just be a book about the experience and perspective of dogs. Paying attention to dogs and their lives would at the same time be paying attention to an important aspect of modern Turkish life. Whether the lady carrying bags of cat food to the alley behind her house, the New Age office worker always posting about shelter animals on her Facebook, or the pharmacist caught on camera fixing up a dog’s paw, Turkey is filled with those who have abided through the long stretch of national chauvinism and the cult of the AVM shopping mall through an ethics of care and maintenance turned towards animals. Whereas Americans treat dogs like their own pampered, unconditionally loving children, a Turkish person can see a dog in the street, living independently in the liminal space between nature and domesticity and help them without the urge to become their exclusive owner. It would make sense that they could also imagine dogs as having their own culture which only liminally fit into their own.

This alternative approach to animal empathy is a good lesson for a foreign book to make to an American reader. I admit that when I first read the book, I went looking for a definitive taxonomy of talking animals out of frustration with the cigarette scene. From classic fables to non-human sidekick movies, talking animals usually do follow one of many clearly defined tropes. But rather than taking things so literally (or figuratively, I suppose), Wûf asks us to think about the experience of dogs on their own terms. This is especially true in terms of the violence we see throughout the book. With its smoking, mine-sweeping, lusting and fighting dogs, Wûf reminds us that in their own bodies, animals are unique and remarkable, and don’t need to be analogized to humans in order to be given permission to feel. In their partial and overlapping homologies with humans, they confound our efforts to either wholly relate or wholly reject their proximity to us. Rather, the dogs of Wûf present us with a better source for empathy, an aesthetics of what Anat Pick calls the ‘creaturely’—the material, the temporal, and the vulnerable. This is an approach to animals in literature that creates connections with animals “via the bodily vulnerability –the creatureliness – we share with other animals” (Pick, 2011, p. 10). What we share is not a commensurate consciousness, but an elemental ability to feel. Thought about this way, Varol’s novel no longer seems like a strange, unsorted allegory. It comes off instead like a story trying its best to show us that dogs too have it rough, that their experience of hunger and injury is not different than ours, that they’re so alike in their feeling bodies that it wouldn’t be outrageous to think that they too might just want a smoke to take the edge off.

*

Matthew Chovanec is the English translator of Gavur Mahallesi by Mıdırgıç Margosyan and of Sinek Isırıklarının Müellifi by Barış Bıçakçı. Chovanec also recently obtained his PhD in Turkish and Arabic literature from the University of Texas at Austin.

Turkish Dude Lit Has a “Dad Rock” Moment: Barış Bıçakçı’s The Mosquito Bite Author

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/by/matthew-chovanec/

[A] stream of academic writing still holds up these dudes and their self-pity as emblematic of national identity.

Turkish dude lit is much like dude lit elsewhere: it deals with the trials of privileged man-boys. Unlike some of the genre’s more vilified geographic variants, though, it has yet to be carefully examined. While grateful for the chance to indulge in it freely, former Asymptote contributor Matthew Chovanec has his qualms; in particular, he argues, pinning Turkey’s Volksgeist on its male antiheroes actually does them (and their readers) a disservice. Enter The Mosquito Bite Author, in Chovanec’s own recent translation: might acclaimed writer Barış Bıçakçı’s subtle parody of the vain male figure pave the way to its survival?

I really enjoy Turkish novels about men wasting away in their comfortable, petty-bourgeois lives. I can’t get enough of them. I love following along, a vicarious flaneur, as the protagonists stroll through my favorite Istanbul streets. I’m charmed by their ability to take just the right line of surrealist poetry from the Ikinci Yeni movement and make it fit as an oracular judgment on their own personal haplessness. I even like reading about them sitting at home, staring at their bookshelves and resenting their wives. Something about them has me consuming these titles with the faithfulness of a reader of policiers or harlequin novels, and Turkey keeps producing them with almost pulp-like regularity. Every decade, it seems, brings its own antihero, yawning at modernist art exhibits, slinking away from military coups, scorning the superficiality that comes with economic liberalization, or trying out the latest fashions in postmodern soliloquy.

While I myself am a voracious reader of highly literate accounts of sociopathy, I appreciate that they aren’t for everyone. As an American, I can also admit that I’ve basically taken a circuitous linguistic route to enjoying works that would face derision back home, reveling as I am in another country’s “Dude Lit.” Laura Fraser describes the genre as one whose “books generally propel a confused, often drug-addled or alcoholic, narcissistic, philandering male protagonist to, well, not self-discovery, but some semblance of adult behavior.” Her description could just as easily apply to the protagonists of Turkish novels like Yusuf Atılgan’s Aylak Adam, Oğuz Atay’s Tutunamayanlar, Vedat Türkali’s Bir Gün Tek Basına, or Ayhan Gecgin’s Gençlik Düşü; they, in turn, make frequent reference to the Slacker International, inhabiting the same fictional universe as Seymour Glass or John Shade.

Despite teeming with such men, these novels have not yet been roped off as Dude Lit. The garish, totemic look of Tutunamayanlar on a bookshelf evokes that of Infinite Jest, but owning the former somehow doesn’t come with the same level of chauvinist insistence. Although the Turkish language already has a fantastic translation for the term “mansplaining,” and scholars like Çimen Günay-Erkol have begun to problematize overt forms of hegemonic masculinity in Turkish fiction, a stream of academic writing still holds up these dudes and their self-pity as emblematic of national identity. I, however, would love to have the pressure taken off of the Turkish male literary canon and the niche tastes of those who, like me, continue to canonize it. I have been eagerly waiting for the Turkish Dude Novel to have its “Dad Rock” moment:

One important thing that happened in the 2010s was that rock music (especially the kind made by white, dad-aged men) drifted to the edges of mainstream popular culture. And though this shift has not yet made up for decades of erasure of more diverse voices, streaming has widened the array of easily accessible artists and perspectives.

The catch is that this has not spelled its irrelevance—quite the contrary. Maybe the gently teasing term “dad rock” cut this music appropriately down to size, removed its albatross of “greatness” and rendered it ripe for rediscovery by the sort of people who might have initially balked at its patriarchal omnipresence.

With a similar recognition of the specificity of the male narcissist experience, perhaps I and others like me might enjoy Turkish petty-bourgeois narcissist novels in peace, without them having to speak for anything more than themselves.

That is why I was thrilled to first read (and now translate) The Mosquito Bite Author (UT Press) by the acclaimed Barış Bıçakçı. The novel follows the daily life of aspiring writer Cemil in the months after he submits his own novel manuscript to a publisher in Istanbul. Living in an anonymous apartment complex in the outskirts of Ankara, Cemil spends his days going on walks, cooking for his wife, repairing leaks in his neighbor’s bathroom, and having elaborate imaginary conversations with his potential editor about the meaning of life and art. Uncertain of whether his manuscript will be accepted or not, Cemil lets his mind wander: he shifts from thoughtful meditations on the origin of the universe and the trajectory of political literature in Turkey, for instance, to panic over his own worth as a writer or incredulity towards the objects that make up his quiet suburban world.

The Mosquito Bite Author follows in the great tradition of the “Turkish Oblomov” by focusing on someone who initially seems to be an undeserving protagonist—much like the titular character in Ivan Goncharov’s work. Borrowing from the narcissistic, petty-bourgeois male novels before it, it relishes in the mundane and the self-absorbed. Cemil stares wistfully at jars of jam, yells at soccer matches, and mopes around the apartment until his wife Nazlı gets home. He has written a manuscript, yes, but as we wait along with him to hear back from the publisher, we aren’t sure whether or not it will end up justifying the attention we’ve given him. If it’s a work of genius, then all of Cemil’s aphorisms and insights will prove to have been profound and poetic. If it is rejected, then we will have spent 150 pages following another one of those failed writer characters we so often get from authors who “don’t have the emotional depth needed to write normal characters,” as Cemil himself notes.

This self-aware literary framing is not lost on Bıçakçı, who gives so many knowing winks to his own writing that we lose track of how many levels of irony we’ve read through. A particularly important strand targets the vain male artist. Bıçakçı’s male characters are subtle parodies, apprehensive idealists whose inane romanticism gets called out by the very women they thought would idolize them in silence. Throughout the novel, Cemil’s artistic project isn’t undermined by deep existential questions, but by the sexist entitlement lying at its core. It becomes increasingly clear that his pretention towards becoming a writer is being wholly underwritten by Nazlı, who supports him financially. He himself admits as much when, at the beginning of the novel, he tells a manager at the publishing house: “‘To tell the truth, my wife is taking care of me now . . . and she’s a doctor so she’s pretty good at it too.’” This caretaking extends to emotional labor as well. In a critical moment towards the end of the novel, as Cemil deals with disappointing news, Nazlı tells him to go read his favorite J.D. Salinger story (“‘I think if you listen to Seymour’s story about Bananafish you’ll feel better’”). Her comment is unintentionally infantilizing—she offers her husband a great book to calm him down, as one might a baby pacifier—and it tears Cemil out “by the roots.” It also lays bare the cultural diminutiveness of the literary canon that he holds in such high regards. But it is precisely this kind of irony which ultimately assures a future for protagonists like him. Rather than pinning the fate of the Turkish soul on the male antihero, The Mosquito Bite Author takes the pressure off him by revealing his idiosyncracies as just one particular lived experience.

Paradoxically, once Cemil’s stream of consciousness and intertextual psychodrama cease to be read as allegories of national identity, they offer a vivid portrait of contemporary life in Turkey. A few chapters of the novel, for example, relate the construction of his nondescript apartment bloc back in the 1980s, treating us to a fascinating, understated account of urbanization and the overwhelming influence of the construction sector on Turkish politics. Remembering his college days, Cemil unwittingly dramatizes the awkward process of student depoliticization in the years after Turkey’s harsh post-coup crackdown. When he takes the bus to do errands, we get to sit in traffic and look at the absurdly built landscape which defines the real lived experience of most Turks. Bıçakçı uses the breathing room provided by his bumbling, introspective protagonist to create just enough distance for the political and the historical to come into focus.

Decentering the male petty-bourgeois narcissist not only comes as a relief for niche readers like me; in addition, it can free other social groups in Turkey from the burden of providing anthropological insight to foreign readers. Books that center on the experience of the country’s marginalized often perpetuate an exoticized vision of a foreign land in well-meaning liberal audiences. The Turkish author Ayfer Tunç says she resents the international publishing market for this “new orientalist” perspective, expecting “exotic novels full of elements below their standards.” Token subalternity, I can only imagine, must feel like an albatross too. That is why I hope that Turkish Dude Lit can channel the power of universally recognizable slackers, helping readers from other countries have both less titillating expectations and higher standards regarding Turkish culture at large. Ironically, a novel about a typical, boring, self-centered Turkish dude might end up providing just such a widely shared experience, offering literature that rather than exotic is simply niche.

Image credit: Teymur Ağalıoğlu

Bioregional Imaginings in Two Recent Mesopotamian Novels

https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/42094/Bioregional-Imaginings-in-Two-Recent-Mesopotamian-Novels-42094

In a recent interview with Jadaliyya, the journalist and researcher Khalid Suleiman talks about his new book on the looming threats of drought and climate change in Iraq and explains the special role that art and culture can play in raising environmental awareness in the country. Suleiman makes special note of science fiction works that imagine future worlds of ecological catastrophe: ones in which the ice sheets have melted and Basra has drowned in seawater, or where climate change has made the surface of the country too hot for human habitation. The article gives the example of the story “Graffiti 2042” by Muhammad Khudair in which residents are driven by extreme temperatures to build a “subterranean” city. During a brief excursion above ground the story’s main character sees a friend of his painting a mural painted with the words:

“Woe to the prophecies which described what would be our ugly distorted lives”

تعساً للنبوءات التي رسَمت حياتَنا الشوهاء

Unfortunately, while environmental catastrophe has already begun to unfold in Iraq, Suleiman claims that practically nobody but fiction writers are thinking seriously about these threats. The prophecies, it seems, are not being heeded.

Not only has recent fiction in Iraq envisioned future environmental dystopia, but it has also worked to retrieve historical landscapes, and to reimagine the natural environment of Iraq as it exists today. While works like those by Muhammad Khudair work through the conventions of science fiction, other genres have used what Tom Lynch et al. refer to as “the bioregional imagination.”[1] Bioregionalism is a way of thinking about place that is grounded in the natural environment and people’s relationship to it. The term originated as part of the environmental movement referring to efforts to move past arbitrary political geographies in favor of thinking about place as being organized around naturally-determined boundaries such as ecosystems and watersheds. A bioregional imagination is those efforts to pay closer attention to what makes a place biotically unique, bringing with it a sensibility towards the natural world and our connection to it. A biological imagination also has the potential to act as a proactive force in an environmental movement forever rallying around the next disaster or impending crisis, allowing it instead to reimagine human communities that live sustainably in place.

Using the term bioregional imagination helps to reframe our assumptions of how generic conventions are being used, and to grant us a better understanding of a book’s implicit biocritical themes.

Iraq’s own bioregional imagination is overwhelmingly focused on its waterways. For a country located almost completely within the Tigris-Euphrates watershed, it is no surprise how often Iraqi novels and poetry invoke the nation’s lakes, rivers, and riparian zones, albeit most often in tangential ways or in the literal background.[2] But it is precisely for this reason that the concept of the bioregional imagination is so eminently useful. It can help us both reveal environmental themes within fiction that are otherwise not explicit or didactic, and can also point us towards unique narratological framings and thought-provoking conceits used in novels without having to rely on overused and one-size-fits-all genre designations like “magical realism” or “picaresque novels.” Using the term bioregional imagination helps to reframe our assumptions of how generic conventions are being used, and to grant us a better understanding of a book’s implicit biocritical themes. Closer attention to the role of water bodies and ways in novels reveals how they are quite historically dynamic and often constitutive of the cultural worlds that novels depict.

Environmental Memory in Al-Sayyid Asghar Akbar

Published in 2012, Al-Sayyid Asghar Akbar by Murtedha Gzar has been hailed as a local adaptation of magical realist conventions to the Iraqi context. The novel tells the story of Al-Sayyid Asghar Akbar, an enigmatic character who arrives in the city of Najaf in 1871 by boat, and proceeds to peddle a sort of prophetic genealogy to the residents of the city. The novel uses a playful and exaggerated historical fiction to recount much of the history of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Najaf, taking up themes such as religious patronage, political cronyism, and military imperialism. Much of the reason for the designation of the novel as “magical realism” comes from the novel’s capricious mix of fact and fiction. Asghar Akbar’s own story, for example, is narrated unreliably by his three granddaughters from the distant vantage point of 2005. Through this theme of genealogy and family history, the history of the city is as well re-narrated from multiple contradictory angles. Yasmeen Hanoush has detailed the ways in which Gzar’s novel depicts the city of Najaf’s using unusual temporalities in a way that shapes the novel’s suspicious and even potentially magical eponymous character.[3]

In quite a similar way, the geography of the city, and in particular its hydrology, is so continuously remapped as to make it come under suspicion. This eliciting of suspicion is exactly how Gzar triggers our bioregional imagination. As Lynch, Glotfelty & Armbruster say “one of the tools bioregionalists often employ to reterritorialize their lives and place is mapping. Liberated from the control of the official cartographers of states and nations, map-making can be an empowering tool of reinhabiting and reimagining place, allowing us to visualize in a nearly infinite array of contexts and scales the multiple dimensions of our home places.”[4]

One particular plot point that Hanoush focuses on in her article is the disappearance of a small imaginary town called Baghlat Abbas, which was told to have been located on the shores of the Sea of Najaf, an almost supernatural water body which once existed directly west of the town. Although located far inland and separated from the Euphrates river by several miles, popular lore adapted into the book tells of how Indian and Chinese traders were once able to pull their boats up to the city directly. In fact, the eponymous character of the novel himself arrives in Najaf on a ship called the Baghlat Abbas.

Due to association with other fictive and uncanny elements including the unusual ship, its eccentric captain, and the timeless character of the place, the “Sea of Najaf” (which is documented to have existed during a former historical era) comes across as a fictive place in the novel.[5]

But there is also something very natural about the case of Baghlat Abbas and the Sea of Najaf as well. Although it may seem like an element from science fiction or fantasy, the water body known as the Sea of Najaf has in fact taken many different shapes throughout history. A look at the historical record of explorers and rulers, dating back as far as Alexander the Great, details an environment in constant flux. Overall, however, the Sea of Najaf for much of its history existed as a large freshwater lake whose proportions shifted according to seasonal rainfall. The Portuguese explorer Pedro Teixiera passed through Najaf in 1604 and described the lake in the following way: “In the rainy season, they are swollen by much water from that desert and form here as it were a great sea; whereof the water-marks bear witness, showing a difference of fifty palms between high-water-mark and the level at which I saw it, in the reason of least water. This lake is of no regular form, but has various arms.”[6] And rather than the stuff of fantasy, pilgrims from India, as well as European explorers, once really did arrive in the city by boat. As a wetland depression area, the Sea of Najaf was once fed by various inlets, including the Euphrates itself (scientists have confirmed that the river once flowed to the West rather than the East of the city). The Sea in fact only disappeared completely in the late nineteenth century when an Ottoman sultan is alleged to have blocked its main inlets with large rocks. After definitively drying in 1915, the area would become a collection of predominantly wetlands, orchards, and farmland, fed on a seasonal basis by heavy rains as well as a constant low-volume influx of water from springs, oases, and groundwater. The Sea of Najaf remained in this state for over one hundred years, enough time for several generations to pass and living memory of the Sea as a waterbody to come to seem like the stuff of legends.

However, in the early months of 2019, a flurry of news articles were published proclaiming the return to life of the Sea of Najaf. After a series of torrential rains and flooding in from several inlets, the depression area filled completely with water, even requiring local residents to construct earth mounds to prevent the flooding of developed areas of the city suburbs. Once the water settled, the remarkable sight of a large lake, returned to life, drew visitors from all over the country who spent their spring vacations visiting the newly reformed lake. Drone footage shows a long line of cars with families swimming in the water and grilling fish. The revival of the lake has also inspired speculators and developers eager to build tourist facilities and even a canal which would once again join the Sea to the Persian Gulf.

Just as Gzar’s attempts to undermine received narratives of Najaf’s political and social history through a strategy of unnatural narratology, the subtle references to hydrological elements like the Sea of Najaf in the novel encourages us to disabuse ourselves of the habit of mind which sees water bodies and ways as geographically and historically fixed. By asking us to question the history of Baghat Abbas and the Sea of Najaf, Gzar performs what Serenella Iovino calls narrative re-inhabitation: “restoring the ecological imagination of place by working with place-based stories [and] visualizing the ecological connection of people and place through place-based stories.”[7] Just as the contradictory stories of Baghlat Abbas lead the granddaughters to go seek out the location of the town themselves, the novel Al-Sayyid Asghar Akbar encourages readers to ask what about the city’s mysterious hydrological history is fact and what is fiction. As Iovino says, a historical curiosity also leads one to better understand the ecological connection of people and place. For example, there is an important link, alluded to at several points in the novel, between religious patronage and water systems. As a sign of the city’s decline, residents complain about bones of the deceased swimming in the water of drinking wells and an outbreak of dysentery is traced back to a shallow well in Kufa nearby. In fact, the provision of drinking water by the construction of the “Hindiyya Canal” by Shi’i Indian Patrons in the form of a religious endowment in the eighteenth century is credited with completely reviving the city and making it a thriving destination for Indians arriving by ship. The entire machinery of the religious tourist economy of the city was lubricated, so to speak, by the shifting infrastructure of waterways.

Political Reterritorialization in The Old Woman and the River

The Old Woman and the River (Al-Sabiliat, 2016) by the late Kuwaiti author Ismail Fahd Ismail also allows readers to explore the waterways of Iraq, specifically the Tigris-Euphrates Delta and the Shatt al-Arab, with a bioregionalist imagination. The novel tells the story of an old woman named Um Qasem who is forced to evacuate her native village Sabiliyat on the Iran-Iraq border with the outbreak of the war between the countries in 1980. In order to protect its citizens, the government literally reterritorializes the village by putting it within an area of military zone operations, forcing the old woman and her family to move to safety in Najaf. But Um Qasem quickly becomes homesick and feels useless living in an adopted city. When her son brings her an orange to eat, she is overcome by nostalgia for her homeland remembering the orange orchard she used to see across the Chouma River.

Her imagination rises into the air to take form there. The place where she’d lived is the taste and savor in the mouth, the spectacle and image in the mind’s eye. She feels herself drifting away. If only she could go back there. She shuts her eyes and sees her husband moving back and forth between their conjugal room and the Hilawi date tree.[8]

The old woman is so overcome by her connection to her origins, remembering her late husband and a specific tree in her home in the same breath, that she decides to simply walk back home with her donkey named “Good Omen,” a journey that would take approximately eighty-five hours to undertake.

In her review of the novel, Marcia Lynx Qualey refers to Um Qasem as Don Quixote, with Good Omen playing the role of both her trusty steed and Sancho Panza. But using the shorthand “quixotic” misunderstands something crucial about Um Qasem’s motives. One could easily dismiss her return home as a simple form of senile obstinancy or simple homesickness, but that dismisses her actions as a kind of whimsical insanity. The term overlooks all of the ways that Um Qasem’s behavior both on the road and when she gets back to Sabiliyat are reflective of a deep and intentional ethics of stewardship and care. Her seemingly eccentric actions throughout the novel make sense as the actions of a woman deeply rooted in and responsible to a specific place. Her fantastical visions are not the equivalent of Quixote’s seeing monsters in windmills, but come from her own bioregionalist imagination. That is to say, they are animated by the stories and modes of discourse of her specific bioregion, and illuminate ecological crises where others cannot see.

Evading military convoys and security checkpoints, Um Qasem arrives home on foot. Once back in Sabiliyat she is dismayed to see what has happened ever since her village in the short time she was away. It seems as though the reterritorialization of Sabiliyat as a military operation zone was not merely a technicality. She discovers that the soldiers have built a mud dam across the Sayyid Rajab and Chouma river in an effort to thwart secret amphibious attacks by Iranian divers. This damming seems to have immediately dried out the area around her village and disturbed both the plant and animal life of the region. She surveys the area and sees all kinds of unsettling signs in the natural world. Being intimately familiar with the ecosystem, she can see all the signals of its disequilibrium. Close to her village, she notices the unchecked growth of sawgrass, a sign of neglect. She and Good Omen also startle a wild boar in a field, as wild animals have settled and made dens in the absence of humans. Elsewhere, the dense foliage and orchards filled with pomegranate, apricot, orange, and tangerine trees have all wilted. Um Qasem is dismayed.

It pained her to see the Shatt surging with water and pulsing with life while these rivers were reduced to deep muddy trenches overgrown with reeds and papyrus plants. What gave them the right to sentence the orchards to death?”[9]

Seeing the desperate state of her bioregion, Um Qasem has no choice but to become its clandestine steward. She begins planting rose cuttings and fixing up the houses of those who have left. She also tries to care for the animals whose habitats have been destroyed by the dam. She takes a particular interest in a group of frogs who are slowly dying in a stagnant cement pool. Their desperate state drives her finally to sabotage military infrastructure by bringing down the dam during a thunderstorm, re-irrigating the orchards and streams surrounding her village. These types of actions are referred to by Berg and Dasmann as acts of re-inhabitation: “learning to live-in-place in an area that has been disrupted and injured through past exploitation.”[10] Um Qasem is not merely wandering around like a madwoman, trying to go back to life as normal as though a war weren’t taking place. She is instead fully aware of the damage the war has already caused, and is re-inhabiting her village with a specific eye towards repair. Seen in this way, Um Qasem is no longer choosing to ignore the realities of the military zone, but is instead acting within the unique “terrain of consciousness” of her own bioregion as Berg and Dasmann call it.

She is eventually caught by the soldiers stationed nearby who are bewildered both by her ability to bring down an entire dam by herself, and by the fact that she felt a need to bring it down in the first place. After a long but sympathetic interrogation, Um Qasem finally reveals her motives.

Lieutenant Abdel Kareem asked her sympathetically, “You’re concerned about the land getting watered.”

“It’s a sin to kill the fruit of the earth.”[11]

But rather than laughing her off as raving mad, or punishing her as a saboteur, the soldiers are actually receptive to her suggestions that they place pipes underneath the dams to allow for partial irrigation. That she is able to endear herself to the soldiers and even win them over to her plan is due to the fact that she has acted as a local steward for them as well. From the moment she arrives in Sabiliyat she plies them with pickled vegetables and plates of grilled local fish. She even begins to play the role of a sort of adopted mother to one of them by the end of the novel. In a word, she is able to win them over to her biological imagination and her re-inhabitory project.

Conclusion

The interview with Khalid Suleiman mentioned at the beginning of this article emphasizes repeatedly the unique form and style that he took in composing his study of drought and climate change in Iraq in his book, using “a journalistic or literary approach that avoids theoretical language.” When asked what motivated him to write the book, Suleiman laments “the vast space that separates academic conferences and forums from the daily reality of people.” And so he begins both the interview and his book by showing off the power of the literary approach by use of a long story from his own life about a berry tree that his father planted in his house when he was a child. Next to the berry tree Suleiman’s father also digs a well that is initially dry and from which they never drink. But with time the well slowly fills and can be used to sustainably nurture the tree, which becomes an oasis for humans and animals alike. The story serves as a beautiful parable of the vernacular knowledge of environmental stewardship that Suleiman’s relatives “conducted through an organic and sensory relationship between the population and the dry landscape where our ancestors had chosen to live.”

What better way to describe bioregional literature’s mechanics than as fiction which mimics this “organic and sensory relationship” in its own engagement with readers? Rather than citing shocking statistics or warning of imprending crisis, Suleiman tries to build this kind of relationship with readers by using stories, making relatable and visceral his proactive attempt to reimagine human communities that live sustainably in place. Narrative is a profoundly effective invitation to participate in reimaginings of place because it does the work to “build a rapport” with readers; both by building a relationship of communication but also more literally by building a rapport in the word’s original sense of “an act or instance of reporting.” Likewise, bioregional fiction in Iraq roots its stories by working patiently with local conditions. Novels like Al-Sayyid Asghar Akbar and The Old Woman and the River creatively reimagine Iraq’s water bodies and ways using the entire narrative toolbox of speculative fiction— dubious narrators, fantastical events, eccentric characters, and subtle allegories— all to build out an entire infrastructure for creative reimagining focused on natural systems. It also adapts these conceits to local conditions, using everything from Shi’a clerics to the Iran-Iraq War, as a way to make these strange locations undeniably familiar. These novels do the work to coax readers into suspending disbelief for the sake of the fictional story in order to eventually have them train their speculative attention on places in the real world that need desperately to be reimagined.

[1] Milne, Anne, Bart Welling, Chad Wriglesworth, Christine Cusick, Dan Wylie, Daniel Gustav Anderson, David Landis Barnhill et al. The Bioregional Imagination: Literature, Ecology, and Place (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 3–4.

[2] And one might be tempted here to refer to the region as Mesopotamia rather than Iraq as a way to emphasize it as a bioregion if not for its anachronistic and orientalist associations of the term.

[3] Murtaḍa Kazaar, al- Sayyid asgar akbar riwayat (Beirut: al-Tanwiir li-l-Tibaʻa wa-l-nashr wa-l-tawziʻ, 2012), 156.

[4] The Bioregional Imagination, 6.

[5] Yasmeen Hanoosh, “Unnatural Narratives and Transgressing the Normative Discourses of Iraqi History: Translating Murtaḍā Gzār’s Al-Sayyid Aṣghar Akbar,” Journal of Arabic Literature 44, no. 2 (2013): 158.

[6] Pedro Teixeira, The Travels of Pedro Teixeira, trans. William F. Sinclair (London: 1902), 45.

[7] Serenella Lovino, “Restoring the Imagination of Place,” in The Bioregional Imagination: Literature, Ecology, and Place, ed. Tom Lynch, Cheryll Glotfelty, and Karla Armbruster (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 106.

[8] Isma‘il Fahd Isma‘il and Sophia Vasalou, The Old Woman and the River: A Novel (Interlink Books, 2019), 12.

[9] Ismāʿīl and Vasalou, 80.

[10] Milne, 6.

[11] Isma‘il and Vasalou, 150.

Creaturely empathy with desert animals: A Kuwaiti environmentalist’s social media experiment

https://www.madamasr.com/en/2019/10/08/feature/society/creaturely-empathy-with-desert-animals-a-kuwaiti-environmentalists-social-media-experiment/

For the first few seconds, it is not clear what the cavalcade is chasing out in the desert at dusk. The cameraman is filming from the driver’s seat of the moving car, his lens following a small black spot darting between the clouds of dust at the horizon. Suddenly, miraculously, the object zigs right in between the pursuing vehicles and then quickly zags off into the setting sun. At this point the viewer can recognize the object: it is a wolf, panting and exhausted as it tries to escape at full speed. All of a sudden, the thrill of the chase gives way to a sense of dread and deep empathy for the poor, hunted animal.

This sudden emotional shift is likely unintentional. But the hunting video has been reposted by a Kuwaiti environmentalist named Fanis al-Ajmi as a way to bring us in close contact with the wildlife of the desert. Despite the country’s arid climate, Kuwait is home to a stunning range of wildlife: over 420 species of migratory and endemic birds, dozens of mammal and reptile species, and around 800 species of insect. But like many countries in the region, Kuwait’s natural environment has suffered in recent decades at the hands of desertification, urban sprawl, habitat loss, pollution and overhunting. These pressures have led to the local extinction of the Arabian wolf, Arabian oryx, striped hyena, jackal, various types of gazelle and other species which have been recorded in cultural memory as far back as the pre-Islamic Muʻallaqat, the most famous of the qasidah form of Arabic poetry.

Strung out along the route in groups,

like oryx does of Tudih,

or Wajran gazelles, white fawns

below them, soft necks turning,

-Labid (translation by Michael A. Sells)

During a period of crisis for wildlife in the region, Ajmi is bringing a new poetic sensibility to recording the experiences of animals. His curated work offers us an example of how social media can open up an intimate, dramatized and empathetic window into the world of animals.

Fanis al-Ajmi’s argument about hunting

Fanis al-Ajmi is a Kuwaiti engineer and labor activist who has worked on various government initiatives and other environmental stewardship projects. He has been particularly involved in the government’s 10,000 Tree Saplings planting project. With the cooperation of other state agencies, and general enthusiasm from the Kuwaiti public, the project has already planted nearly one million saplings of native plants and trees in Kuwait as of July 2018.

Ajmi’s special contribution has been his use of his social media to make conservation issues come alive in an intimate and unsettling way, to show how environmental destruction is playing out on animals themselves. In the last couple of years his posts have become particularly focused on desert animals, cataloguing especially pictures and videos posted by local hunters. According to Ajmi, his friends and followers regularly send him things they see online and he works to curate a large archive on his Instagram and Twitter feeds. Although much of this content was originally meant to be boastful or entertaining — to show off hunters’ neatly stacked piles of kill — when their content is reposted by Ajmi they are suddenly turned into scenes of wanton slaughter and cruelty. The posts are deeply unsettling and can sometimes be hard to watch. Scrolling through his feed will reveal a mesh bag filled with frightened, captured birds; a gazelle tied-up, having its throat torn into by a pair of hunting dogs; a pregnant rabbit disemboweled, its writhing offspring pulled from its body cavity; wolves chased to the point of exhaustion and then shot. Like the animals used in classical Arabic prose going back to the writer al-Jahiz’s collection of treatises, Kitab al-Hayawan (Book of Animals), these graphic scenes are used to convey what scholar Jeannette Miller calls “the transcendent value of disgust”.

Much of the appeal of hunting in the region is in the way that it invokes an idealized past. Natalie Koch has shown how falconry in particular has worked to romanticize the Arabian Peninsula’s Bedouin past. Hunting is very much tied to iconic representations of Gulf identity, and with the rise of social media it has become a favorite pastime for conspicuous consumption. Hunters post images of fancy weapons, glamorous desert encampments, and ostentatious collections of trophy kills. Ajmi is confronting these invented traditions and ceremonial presentations of hunting by co-opting content for his own narrative. He has a particular story to tell about hunting in the Arabian Peninsula. “Muslims and Arabs once used to hunt out of a sense of need or hunger only, and had beautiful values such as forbidding hunting in the times when animals were mating or when they had new offspring,” he said via email. In the past, hunters had an intimate connection with the land on which they hunted, and understood the seasonal and migratory shifts in the landscape. In contrast to this vision of former symbiosis, contemporary desert ecosystems are under incredible stress due to the ways that hunting practices exploit nature without regard for its welfare. It is estimated that between 1.7 million and 4.6 million birds are illegally killed each year across the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq and Iran. Ajmi gives ample evidence of the ways in which hunters are killing fauna in the hundreds and thousands without regard for natural limits or ecological cycles. His written comments and captions use a traditional ethical appeal, lamenting how hunters have lost their way, no longer hunting from necessity but for selfish purposes like machismo and bragging (al-tabahi wal-tufakhir). In turn, a growing number of people are joining in on the conversation, creating a growing online community of like-minded environmentalists in the region who are making and sharing their own content.

Along with his focus on the immense scale of destruction, Ajmi gives attention to individual animals, emphasizing in animals what they share with humans: what scholar Anat Pick calls the creaturely — the material, the temporal, and the vulnerable. Pick’s beautiful book Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film (Columbia University Press, 2011) argues that these embodied qualities can form the basis of a new ethics, in place of our traditional focus on intellect, emotion, or language — all things which create a harmful separation between us and other species. Ajmi’s work is centered precisely on building this new code of ethics. In one video from November 10, 2018, the camera is zoomed in on a hyena standing on a rock outcropping on the other side of a rocky desert valley.

For seven whole seconds, the hyena stares in the direction of the camera, inviting interpretations of its mental state. Is it naively curious at the sight of distant humans? Is there a look of pleading in its eyes? This intense focus on cryptic animal emotions is reminiscent of the attention paid to the faces of the wolf and his mates in al-Shanfara ’s muʿallaqah.

Wide-jawed, gape-mouthed,

As if in their jaws

Were the sides of a split stick,

Grinning, grim

(translation by Michael A. Sells)

In both the poem and the post, close attention is paid to the movement of the face in an effort to understand the mental state of the animal, something that is ultimately impossible to determine. This scrutiny, nevertheless, draws us in to careful attention and empathy for the hunted animal. In remarkable ways, Ajmi is using digital mediums to recreate many of the rhetorical and emotional experiences that animals have provided throughout the long history of Arabic literature.

The changing desert

In classical hunting poems, seasonal changes in the environment were experienced and understood directly through animals themselves, like Antara ibn Shaddad ostrich kneeling on withered, crackling reeds in the dry reason or Amr bin Kulthum’s camel frisking in the vernal season. By following changes to animals and the landscape, Ajmi’s posts bring our attention to what is new and unnatural in today’s seasonal changes: the results of changed weather patterns as well as direct human harm.

A video from December 16, 2018, shows a patch of green grass growing miraculously in the middle of the desert, blossoming from a surprisingly wet winter. A series of torrential storms had moved through the Arab Gulf the month prior, bringing large-scale flooding: 25 centimeters of rain over four days, more precipitation than Kuwait receives on average in a year. The desert responded by blooming in normally barren places. However, it is neither birds or wild beasts who are frolicking in the temporary meadow, but a group of jeeps skidding about and spinning donuts. The cameraman eggs his friends on and laughs as the cars grind up the grass in their tires. In his commentary, Ajmi is aghast.

“Their actions last seconds but their destruction will last for years, the sand crumbles and the grass is torn up and it will take a long time for the earth to heal itself, why this selfishness and vandalism, what is the fun in that?”

Over the months of November and December, Ajmi tracked both the positive and negative effects of this intense period of rainfall: camels and their offspring drinking at watering holes, city streets being buried in mudslides, and the sprouting of rare flowers in the desert, like the bakhtari flower. While it can not be directly determined, there is an overwhelming probability that changes in seasonal rains are being caused by climate change.

As Bill McKibben says in his book The End of Nature (Anchor, 1989), we must alter our understanding of dramatic acts of nature to incorporate the ways that we now act as the secret force behind them: “If the waves crash up against the beach, eroding dunes and destroying homes, it is not the awesome power of Mother Nature. It is the awesome power of Mother Nature as altered by the awesome power of man, who has overpowered in a century the processes that have been slowly evolving and changing of their own accord since the earth was born.”

A recurring scene in Ajmi’s posts is that of the hunter’s surprise and shock as animals approach them for aid. Several videos show animals risking the danger of humans to seek shade or water, which is provided by surprised, often laughing observers. Lizards run towards the shade of a jeep. In one video, a bird of prey finds salvation in a makeshift watering hole: a bit of water left by humans in a metal can. In another video posted on Twitter, a man provides a draught of water from a spray bottle to a stork perched on top of a watering basin.

What these videos do not depict is the reasons why animals would be desperate enough as to approach humans for water. The famous watering holes and migration routes of the qasidah form of poetry have been disrupted or removed, and the looming transformations that are quickly beginning to unfold due to climate change will pose even graver challenges to the future of wildlife in the region.

In the face of this intense ecological destruction, people are beginning to understand the fragility of wildlife and take steps to act as stewards to the many species of the desert. Ajmi shows hunters untying wolves from nets, a local man who has adopted a pet rock hyrax, and kids petting a monitor lizard and learning that it’s harmless to humans. In one video posted from an account from nearby Iran, conservationists have created artificial watering holes up in the mountains and in remote locations in order to provide water for wild animals. Rather than annihilating God’s creations, Ajmi encourages his followers to be like these stewards of God’s creation. “This ingenuity is what our culture needs,” he writes.

This stewardship is not entirely selfless. The way that Ajmi focuses on the bodily vulnerability of animals acts as a reminder of what may still very well be the fate of man himself. As the climate of the Gulf is set to become, again, increasingly hostile and even potentially unlivable, there is new relevance for understanding what animals can tell us about nature. To ignore the suffering of animals, and to expedite their extinction through excessive hunting is to ignore nature’s warnings for how much the future of our own species may be subject to human cruelty or charity. The presence of animals, whether it be in the rahil — the travel section of a poem — or on Twitter, reminds us that technology and progress can be forces as harsh and blind as the desert itself. As Ajmi’s animals try to survive amongst the dangers of the desert and of humans alike, they offer us an unspoken warning, echoing that offered by the poet Imruʾ al-Qais and his wolf.

Both of us, when we obtain a thing, destroy it, and he who tries to cultivate my land and your land, will surely become emaciated.

Learning the proper posture to become an internet imposter while reading Impostures

https://www.madamasr.com/en/2020/06/03/feature/culture/learning-the-proper-posture-to-become-an-internet-imposter-while-reading-impostures/

A friend of mine recently admitted to me that he often visits women’s clothing websites. He isn’t interested in buying anything, he just does it to mislead the artificial intelligence following him around on the internet. He knows that computers are constantly surveilling him in order to tailor marketing content. But if they would usually be bombarding him with images of razors and whiskey decanters and other products meant to appeal to his demographic, they are instead filling the little ad windows on his websites with pictures of beautiful, demure women in tasteful clothing. They look on affectionately as he goes about his day online the internet in peace — a small victory in the long psychological war we are losing against artificial intelligence.

These days we’re all trying to hide on the internet. Private browsing windows, proxy servers, and VPNs are all just a normal part of internet life. Samir al-Nimr’s article on Mada Masr last year offered a handy three-step guide to hiding your true political opinions from the eyes of the government. But far more insidious than government surveillance, algorithms are designed not only to find out what we think and want, but to get us to think and want things in the first place. Jia Tolentino, author of the excellent new book Trick Mirror, speaks about what happens when we let our identities be colonized by capitalism, and end up completely identifying with the online marketplace.

“the things that you see are the same things that everyone else sees. Everything is intertwined with these basically four central networks and what everyone is looking at algorithmically influences what everyone else is looking at … and the programmatic capacity for surprise has dwindled to nearly nothing.”

At stake is not only our privacy, but our autonomy. Tolentino claims that the only escape from the hellscape of the internet would be “social and economic collapse.” But my friend, it seems, has begun to find another way: by using AI’s own gullible logic against itself, he is able to surf in peace. His clever deception has made me wonder where else we could find ways of hiding our intentions and meanings in plain sight online.