When Jerome David Salinger died in January, he had been dodging fans and journalists for more than 40 years. Salinger rose to prominence in the mid-1950s, an era of media expansion in which writers became celebrities, and in which celebrity itself could shape an entire literary career. Like many young writers, Salinger first embraced fame. But he soon came to despise it, famously retreating to small-town New Hampshire and refusing to publish after 1965, though he is rumored to have continued writing. One way he protected himself was by holding tightly to his copyright, refusing permission to publish the personal papers and manuscripts that surfaced over the decades.

The Harry Ransom Center is one of a handful of repositories that house small collections of J. D. Salinger manuscripts. Such collections have generally been sold or donated by the writer’s friends or colleagues, or have arrived at as part of the working files of a magazine that has published Salinger’s work. The Ransom Center’s collection contains letters and manuscripts sent by Salinger to his long-time friend Elizabeth Murray, who sold them to the Center through a dealer in 1968.

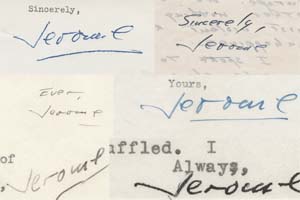

Salinger met Murray in the late 1930s, and over the course of more than two decades (1940–1963) wrote her a series of newsy, often funny letters that provide substantial information about his efforts to publish his stories in various magazines. Most of the letters were written early in his career and show Salinger maturing into a serious writer. They also reveal much of his witty, wry personality; Salinger inhabits various personae in his letters, composing with off-the-wall humor (including an in-joke about Salinger’s taste for Ovaltine) and sometimes signing the name of one of his own characters. He shares his thoughts about other writers—Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Hemingway (whom he met in Paris during the war)—and exposes details about his relationships with three women: Oona O’Neill (who later married Charlie Chaplin), his first wife Sylvia, and his second wife Claire. Salinger enclosed stories with some letters, notably including draft fragments of the first published Holden Caulfield story, “I’m Crazy” (1945), and drafts and fragments of two unpublished works.

Though these materials have long been available to researchers, they remain unpublished and cannot be quoted in scholarly publications. There is little doubt that J. D. Salinger’s death will prompt renewed interest in his life and work among scholars and general readers alike, and we must wait to see how the literary estate will choose to proceed with permissions. In the last few weeks, many of Salinger’s friends and neighbors have spoken openly for the first time about their relationships with the writer, and their openness seems promising: New Yorker journalist Lillian Ross published snapshots and reminiscences of her long friendship with the writer in the magazine, while inhabitants of Cornish, New Hampshire, have eagerly described to journalists the (often marvelously creative) methods they devised to protect their neighbor from curious and unscrupulous visitors alike.

Librarians and archivists have a practical interest in gaining more information about Salinger; the current lack of information about much of his life and work limits our ability to describe the artifacts in our possession, such as books inscribed from Salinger to unidentified recipients and manuscript drafts whose place in the chain of composition cannot be identified without access to earlier and later versions. In the meantime, we continue to encourage those interested in searching the collection to visit the Ransom Center. Visitors to the Ransom Center can view a display of some of the items discussed above in our main lobby from February 26 to March 12. The opening of the display corresponds with “A Tribute to J. D. Salinger,” an event with readings of Salinger materials by Elizabeth Crane, Amelia Gray, ZZ Packer, and John Pipkin. This event is co-sponsored by American Short Fiction.