During the initial staff inspection of Spalding Gray’s papers at the Ransom Center some weeks ago, when each shipping carton was opened and its contents checked for condition, I passed my hands over multiple audio tapes, notebooks, and other documents marked with the single word “Swimming.” It had been around 20 years since I had seen Gray’s critically acclaimed and influential film Swimming to Cambodia, and I decided it was time for a refresher viewing.

Released in 1987, Swimming was the first of Gray’s stage monologues to be adapted for the screen, and hence to reach a mass audience. In it, Gray tells the partly scripted, partly improvised story of his experience as a cast member in the 1984 feature film The Killing Fields, which was nominated for seven Academy Awards and awarded three. This film tells the story of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia in the 1970s through the eyes of an American reporter and his Cambodian interpreter. It offers a powerful critique of American involvement in the events leading up to and following the Khmer Rouge genocide of more than a million Cambodians. Gray had a small role in the film as an American diplomat. His Swimming monologue investigates the many ironies involved in his experience making the film: most prominent is the combination of pleasure and guilt he experienced while on location in Thailand, a country whose idyllic beauty, poverty, and services of all kinds for American tourists produced disturbing contrasts and parallels to the Cambodia of the previous decade.

I rented the film that weekend, and settled in to view it. Less than two minutes in, I hit the pause button, sat back with a laugh, and half-seriously considered heading straight to the Ransom Center to begin searching the shipping cartons. I rewound, watched the opening minutes again, and then sat back to enjoy the remainder of the film, hoping that the object I had just seen had arrived in Austin with Gray’s papers.

As directed by Jonathan Demme, with a soundtrack by Laurie Anderson, the opening sequence shows Gray walking through New York to a small theater, accompanied by upbeat background music (Gray looks both ways earnestly before crossing the street). As he walks, you can see that there is a notebook tucked under his arm. When he reaches the theater, the notebook becomes more prominent. He enters the building, sits down at a table in front of his waiting audience, and begins his performance. He carries it to the stage and places it on the table in front of him as the opening credits begin.

Demme’s camera angle places the notebook at the center of the film viewer’s experience, while cropping out most of Gray’s body (notably, this creates a very different experience to that of the live theatergoers, for whom the combination of speaker, notebook, and table is an uninterrupted, organic whole). The camera clearly shows a schoolchild’s spiral notebook featuring a brightly colored image of Ronald McDonald and his pals playing soccer. The opening credits appear on the screen on either side of the notebook, quite literally emphasizing the centrality of the notebook’s iconography to the film’s message: very soon, the viewer comes to understand that the notebook’s banal iconography of American consumerism and corporate power, layered with Anderson’s buoyant music and the image of Gray walking in his coat through the cold, concrete landscape of New York, is preparing you for the more profound ironies to come.

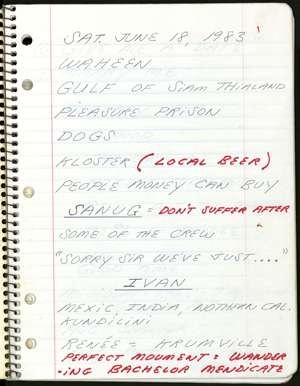

The notebook did, in fact, arrive with Gray’s papers. The Ronald McDonald cover is bright, though the notebook is softened, its corners bumped and curled from much use. The first page in the notebook can be identified as the one visible at the opening of the monologue in the film. One can follow along with the film’s soundtrack while reading the notebook, tracking Gray’s progress through key phrases and words noted in order on the page. Only nine of the notebook’s 50 sheets have been used. Presumably, Gray’s other Swimming notebooks contain preparatory material for this final, brief promptbook.

Critics often mention Gray’s use of notebooks in his monologues; his stage sets generally included a table, chair, microphone, glass of water, and notebook. (Side note: when I looked on Amazon.com for the latest printed edition of Swimming to Cambodia, I was fascinated to see that it features a still-life photograph of this combination of objects on the cover. Without a high-resolution image, I couldn’t tell what kind of notebook was used in place of the original.) As the papers are cataloged, I expect that notebooks for other monologues will surface, and I look forward to seeing how researchers will use these materials.

There are at least two distinct types of research value in this particular notebook: that which its content possesses as a stage in Gray’s compositional process, and that which its look and feel possess as a movie prop. The Ronald McDonald notebook has a kind of magical value too, as an object that represents the major turning point in Gray’s long, richly layered career—the breakthrough moment when this memoirist, playwright, filmmaker, and performer brought his unique vision to a film audience, gaining a prominence that would determine the directions his work took from that point on.

The New York Times drama critic Mel Gussow, whose papers also reside at the Ransom Center, wrote an admiring review of the stage version of Swimming to Cambodia in 1984. He opened the review with this statement: “Were it not for the absolute simplicity of the presentation, one might be tempted to say that Spalding Gray has invented a performance art form.” Little did Gussow know the complexity that would accrete as this work became first a film and then a printed book, gaining new layers of irony as it went along, with no little thanks due to Ronald McDonald’s well-aimed kick at a soccer ball.