Note: This post originally appeared on April 18, 2013.

James Salter’s All That Is (Knopf), his first new novel since 1979, is a reflective work, a reconsideration of many of the themes he has explored in his earlier fiction. Looking back at Salter’s prior novels through his archive at the Harry Ransom Center, one can see the artist at work and better understand the sentiments that guide his craft.

Some notebooks from Salter’s archive can be seen on The Daily Beast.

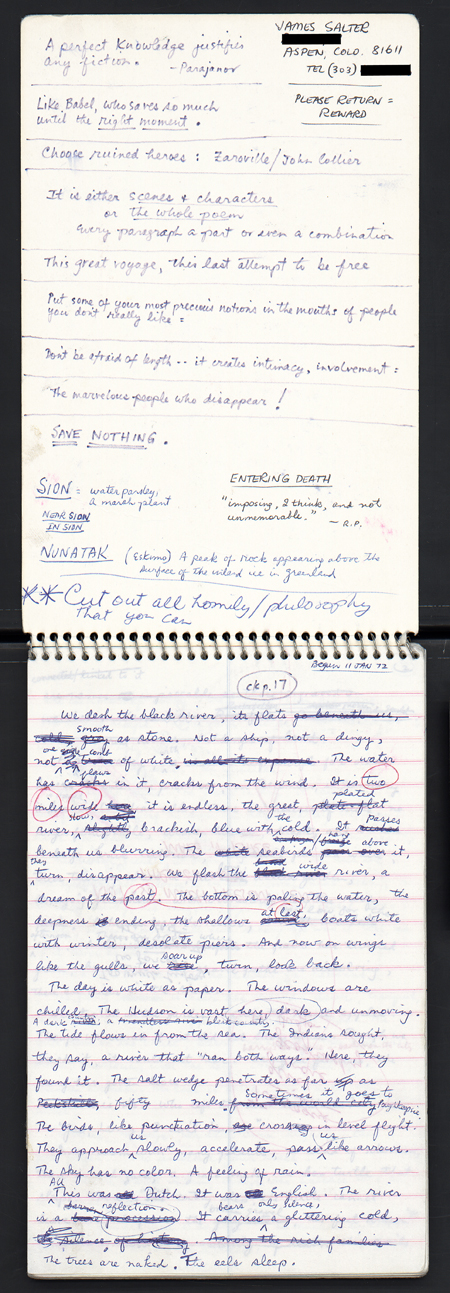

Salter writes his novels by hand, covering notebook after notebook in a tidy, flowing script before typing—and retyping—his drafts. His archive is filled with these notebooks, which not only bear his earliest renderings of a story but also reveal the candid instructions and advice he pens for himself on their inside covers. For example, in the notebook of his 1979 novel Solo Faces, he writes to himself, “Don’t write something they will recognize & accept. Write something that will astonish, that is completely different from their ideas & world & will alter them.” Further down the page is his note, “Brief, lucid, mercilessly clear,” as accurate a description of Salter’s prose style as I have ever seen.

In his opening notebook for Light Years, published in 1975, Salter instructs himself, “Don’t be afraid of length… it creates intimacy, involvement.” The novel itself is an exploration of intimacy and involvement, of love and the slow unraveling of a marriage. Salter revisits many of these concepts in his newest novel. In fact, Light Years may have been a sort of precursor to All That Is. The book’s title is plucked out of the description Salter gave of Light Years in a 1993 interview for the Paris Review: “The book is the worn stones of conjugal life. All that is beautiful, all that is plain, everything that nourishes or causes to wither.”

Prominently recorded on the inside cover of Salter’s first notebook for the 1967 novel A Sport and a Pastime is an instructive quote by André Gide: “Write as if this were your only book, your last book. Into it put everything you were saving—everything precious, every scrap of capital, every penny as it were. Don’t be afraid of being left with nothing.” This advice must have been especially poignant for Salter. He succinctly and emphatically reinforces this sentiment within his notebook for Light Years: “SAVE NOTHING.”

Pasted inside Salter’s opening notebook for Cassada, the 2001 retelling of his 1961 novel The Arm of Flesh, is a photograph of military planes not unlike the ones flown by the book’s characters and by Salter during his 12-year career in the U. S. Air Force. In his notebook, Salter outlines a straightforward, three-part plan for writing the novel:

“SELECT

INVENT

EXPLAIN A BIT”

There are no notebooks in Salter’s archive for his first novel, The Hunters, which was published in 1957 when Salter left the military to become a professional writer. The only draft of the novel in Salter’s archive is typed and labeled, “First submitted draft, originally titled “A Patron of Tokoshi’s” by John Eden” (a pseudonym). Inserted into the draft is Salter’s typed outline of the novel, titled “Rough Re-Outline,” which is covered with the checkmarks of progress and Salter’s handwritten notes. A hallmark of Salter’s creative process, detailed outlines can be found throughout his archive for his subsequent novels.

Salter’s notebooks and outlines reveal a deliberate author at work, one who has a clear vision of both the novel he wants to create and the one he wants to avoid. One of his most illuminating instructions to himself, written and underlined on the inside cover of his notebook for Solo Faces, is the simple note: “Write for readers like yourself.”