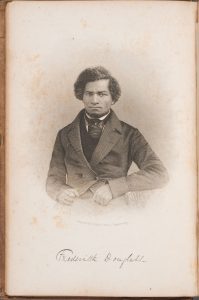

February 20, 2017, marks the 122nd anniversary of Frederick Douglass’s death. Douglass (1818–1895), an abolitionist and activist for civil rights, was a gifted writer and orator.

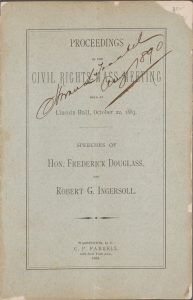

His first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, was published in 1845. It recounted his life as a slave and his escape from slavery. His second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, appeared in 1855 and is part of the Center’s collections. The Center also holds the published proceedings of the Civil Rights Mass Meeting held October 22, 1883, at which Douglass spoke.

The meeting was prompted by the Supreme Court’s ruling, with one justice dissenting, that much of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional. The act was intended to “protect all citizens in their civil and legal rights… whatever nativity, race, color, or persuasion, religious or political.” It sought to prohibit discrimination in public transport and public accommodation and to prevent disqualification for service on juries “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

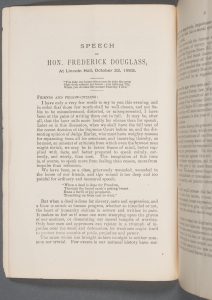

Douglass was introduced to the audience as “a man who needs no extended introduction to an American audience; a man whose fame, not confined to the borders of his own country, has gone throughout the civilized world.” Douglass called his listeners’ attention to the significance of the Supreme Court ruling, arguing that:

We cannot… overlook the fact that though not so intended, this decision has inflicted a heavy calamity upon seven millions of the people of this country, and left them naked and defenceless against the action of a malignant, vulgar, and pitiless prejudice.

It presents the United States before the world as a Nation utterly destitute of power to protect the rights of its own citizens upon its own soil.

It can claim service and allegiance, loyalty and life, of them, but it cannot protect them against the most palpable violation of the rights of human nature…

The stakes, Douglass claimed, were larger than they might appear because “a wrong done to one man, is a wrong done to all men.” He continued:

“Color prejudice is not the only prejudice against which a Republic like ours should guard. The spirit of caste is dangerous everywhere. There is the prejudice of the rich against the poor, the pride and prejudice of the idle dandy against the hard handed working man. There is, worst of all, religious prejudice…”

Douglass helped his audience understand that the ruling impacted all Americans.

Douglass lamented an earlier period in the Supreme Court’s history in which an attempt at discerning constitutional intention led the justices to support the Fugitive Slave Act. He longed for “a Supreme Court which shall be as true, as vigilant, as active, and exacting in maintaining laws enacted for the protection of human rights, as in other days was that Court for the destruction of human rights!”

Frederick Douglass devoted his life to the causes of equality and liberty. An ardent supporter of women’s rights, Douglass attended a meeting of the Women’s National Council on the last day of his life. In his obituary, the New York Times observed, “It is a singular fact, in connection with the death of Mr. Douglass, that the very last hours of his life were given in attention to one of the principles to which he has devoted his energies since his escape from slavery.”