I visited the Harry Ransom Center last July to research bilingual and multilingual dictionaries, grammars, and language manuals printed in England during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Studying these multilingual sources alongside drama offers us a new and more cosmopolitan avenue into the works of playwrights such as William Shakespeare, Thomas Kyd, and Ben Jonson. These plays are full of foreign words, interpreter figures, and scenes of multilingual practice and translation. Renaissance England was, to borrow the title of John Florio’s 1598 Italian-English dictionary, a “world of words.”

I was grateful for terrific research assistance from the library staff, particularly curator Aaron Pratt, who connected me with a variety of exciting primary sources in the Pforzheimer, Aitken, and theatre collections. (For early modern researchers, the Ransom Center’s early book collections include a large number of messy, scrawled-upon, and curiously-bound books.)

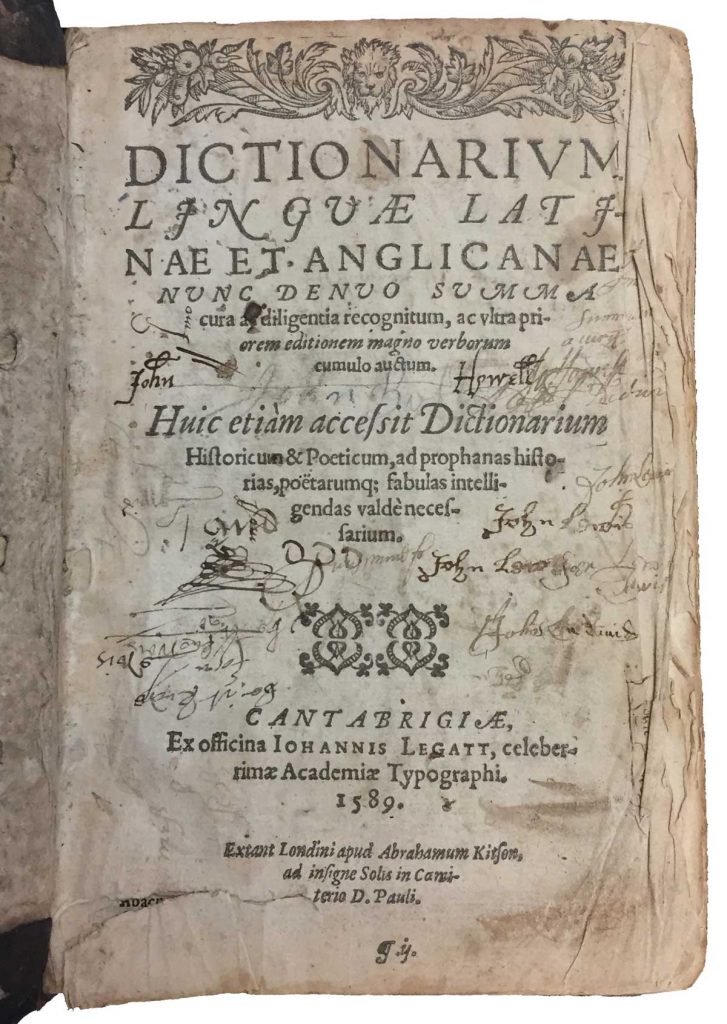

Because I am interested in grammars and dictionaries, I spent some quality time with a ragged copy of Thomas Thomas’s Dictionarium linguae latinae et anglicanae, printed in Cambridge in 1589 (HRC shelfmark Ag T367 588db). My research focuses mostly on vernacular languages and literatures, but Latin occupied a central place in the world of early modern England, too, particularly among learned readers. These were the kinds of readers who would pick up the educational subtexts in a play like Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy, which deals with French, Italian, and Spanish, but also Greek and Latin.

Like dozens of dictionaries I have seen, this copy of the Dictionarium has an array of stray marks and inscriptions from its early owners: John Howell, John Lewis, John Butler, and Robert Butler, to name a few. At the same time, this is a fairly rare and unusual book.

I say rare because the English Short Title Catalogue—the standard bibliography recording English books published before 1801—only documents four known copies: two at Cambridge University, one at the University of Illinois, and this one. Could the users of this book—students, one imagines—simply have read them to pieces? I also say unusual because this book’s title page features a signature—little symbols at the bottom of the page that help a binder assemble a book correctly—when most books printed in early modern England do not.

If you look at the bottom of the title page, you can see it plainly: ¶ij. (I am currently thinking about signed title pages in relation to another book, the first printed English translation of René Descartes’s Discourse of a Method, so I was particularly interested by this feature.) Not only is the book useful to researchers interested in language, it is also a curious artifact for those studying the early development of the printing industry in England.

In addition to grammars, dictionaries, and other word books, I spent my time looking at printed plays. Fortunately, the Ransom Center has a large collection of copies of Ben Jonson’s Workes, a book that made a significant claim for the literary value of theater and drama in Shakespeare’s time, and which recently celebrated its 400th anniversary in 2016. (I should mention there was a bit more excitement about the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, which occurred in 1616 as well.)

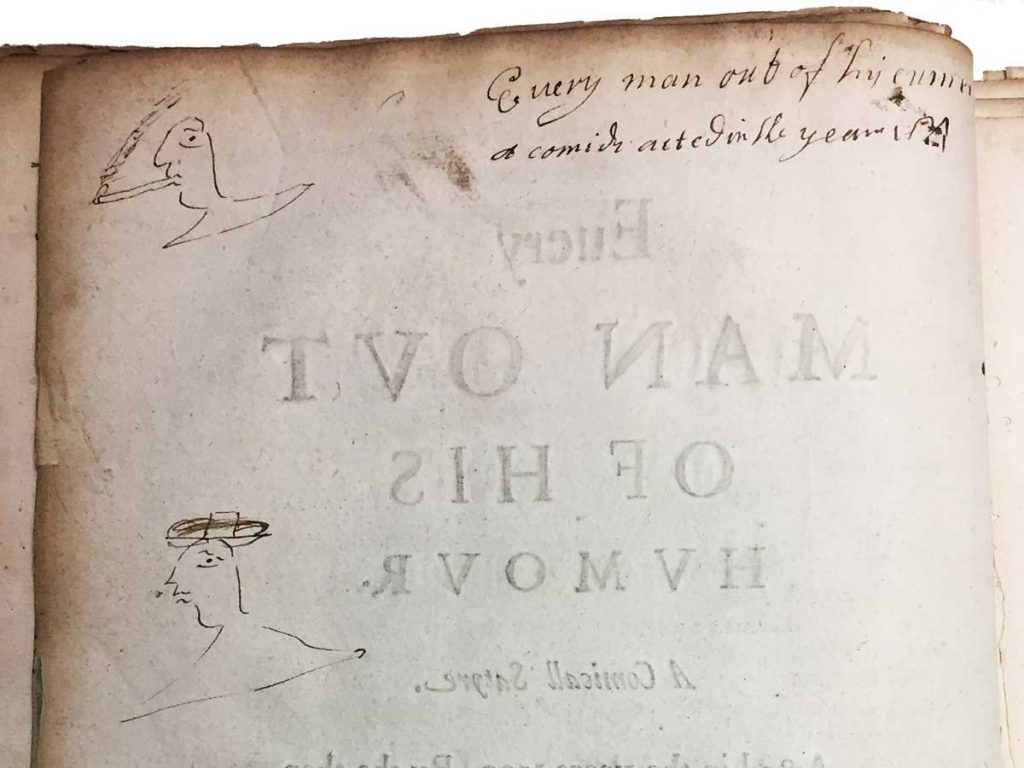

Some of the Ransom Center copies of the Workes are pristine and elegantly bound, but others have seen better days—and I don’t say that disparagingly. These messy books interest me immensely because they tell stories that are often overlooked. Here, you find split or missing spines, detached boards, and copies that are “made-up”—that is, assembled from other fragmentary copies. The curators very generously and patiently allowed me to get my hands literally dirty with these books, and I uncovered some fascinating evidence of seventeenth-century Jonson reception in the process.

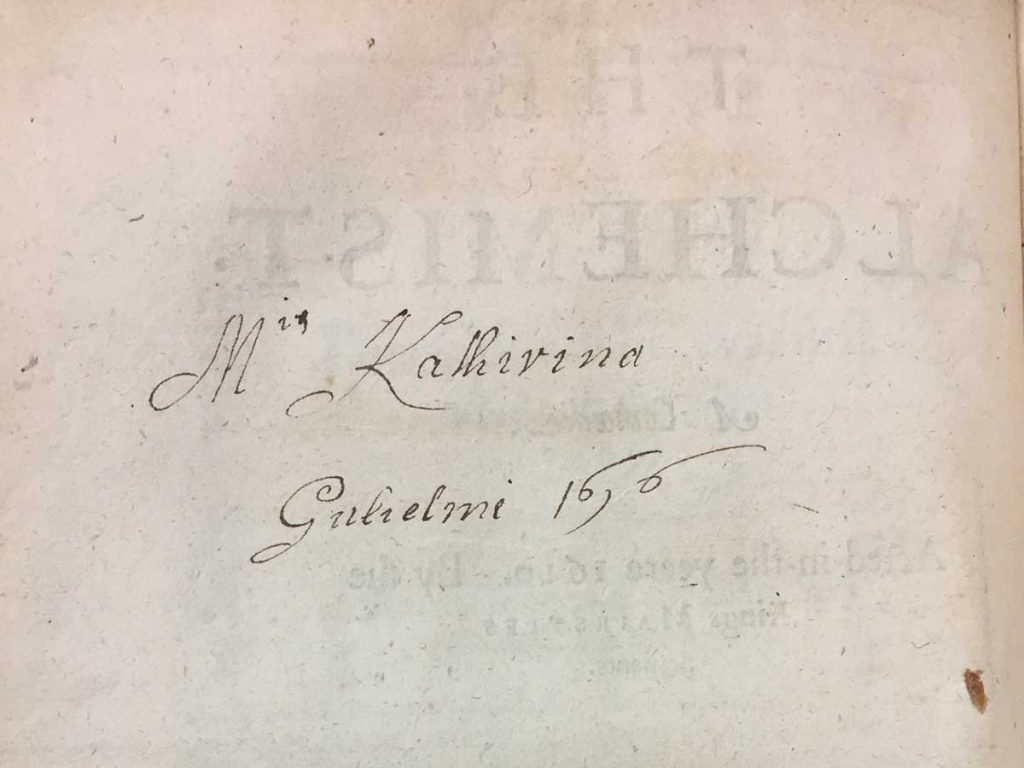

My delicate searches through these folios took me through a host of signs of early use: unusual bindings, doodles, drawings, pen trials, indications of stage business, inscriptions of all kinds. Most exciting for me was an inscription I found in a large-paper copy of the 1616 Workes with a very split binding and the quires exposed (call no. Ah J738 +B616am). There are scribbles throughout this book, but because I am interested in connections between Renaissance England and speakers and readers of French, Italian, and Spanish, I was especially intrigued by the signature of a seventeenth-century user of this book: “Kathirina Gulielmi.” This I found on the verso of the title page to the comedy The Alchemist (below, you can see the printed letters making up the play’s title on the reverse side of the leaf.) I see “1676” in the numerals that follow Gulielmi’s name; it seems clear that this reader signed the book during the seventeenth century.

The Alchemist is a play that fascinates me for its fluid treatment of linguistic and cultural designations. At one point in the comedy, a character named Surly disguises himself in a Spanish costume in order to discover the fraudulent activities of the play’s tricksters. It seems likely that this costume is the one named later in the comedy as “Hieronimo’s old cloak, ruff, and hat,” a clear nod to the multilingual protagonist of Thomas Kyd’s ultra-popular Spanish Tragedy. And indeed, in The Alchemist, this Spanish outfit is accompanied by Spanish words and phrases, which appear in italic type in Jonson’s folio. This play takes place in London and has been designated as a “city comedy” by many critics, but its multilingual and foreign elements gesture beyond England’s borders in significant ways. What happens, I ask, when a “city comedy” stretches past the city, and into other languages and cultures?

I have published on the way Jonson both draws upon and obscures his connections to Continental literature in a different comedy, Epicene: Or, The Silent Woman, particularly in terms of his representations of women. So: what do we make of this Italian name, a seventeenth-century woman’s name, appearing in the pages of Jonson’s Alchemist? Might we be able to trace a path from the multilingual marginalia in this book to the flexible play of languages and identities in the comedy? Is this “Kathirina” Italian, or is she simply experimenting with a Latinate translation of her own name, as countless writers—including John Milton—did?

This copy of Jonson’s Workes offers a way to connect our knowledge about seventeenth-century readers of plays with the reception of English literature beyond England’s borders. Additionally, it stands as yet another reminder that we have a lot to learn from dirty, scribbled-in copies of these plays, language manuals, and dictionaries—both in British and North American libraries, and in European libraries, too.

Andrew Keener is a Ph.D. candidate in English at Northwestern University. His dissertation, “Theaters of Translation: Cosmopolitan Vernaculars in Shakespeare’s England,” analyzes multilingual dictionaries and language manuals alongside plays by Shakespeare, Thomas Kyd, and Ben Jonson in order to recover the cosmopolitan and multilingual voices in the period’s printed and staged drama. Keener was supported by a Harry Ransom Center dissertation fellowship jointly supported by the Creekmore and Adele Fath Charitable Foundation and The University of Texas at Austin Office of Graduate Studies.