In London, the Victoria & Albert Museum extended the run of its 2018 exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, remaining open for 48 hours straight in order to accommodate demand. In Mexico City, lines regularly snake around the block for entry into Casa Azul, the birthplace of Frida Kahlo and the house in which she lived with husband Diego Rivera until her death. Museums all over the world have hosted displays of Kahlo’s paintings and personal possessions in recent years, and Kahlo’s likeness appears on everything from phone cases to protective face masks, from clothing to home furnishings, from tequila bottles to dolls.

Twenty years after her death, increased international interest in Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954) began to percolate in the late 1970s, when her work was met with renewed interest by political activists and feminist scholars. Today it is easy to see that “Fridamania” is in full swing.

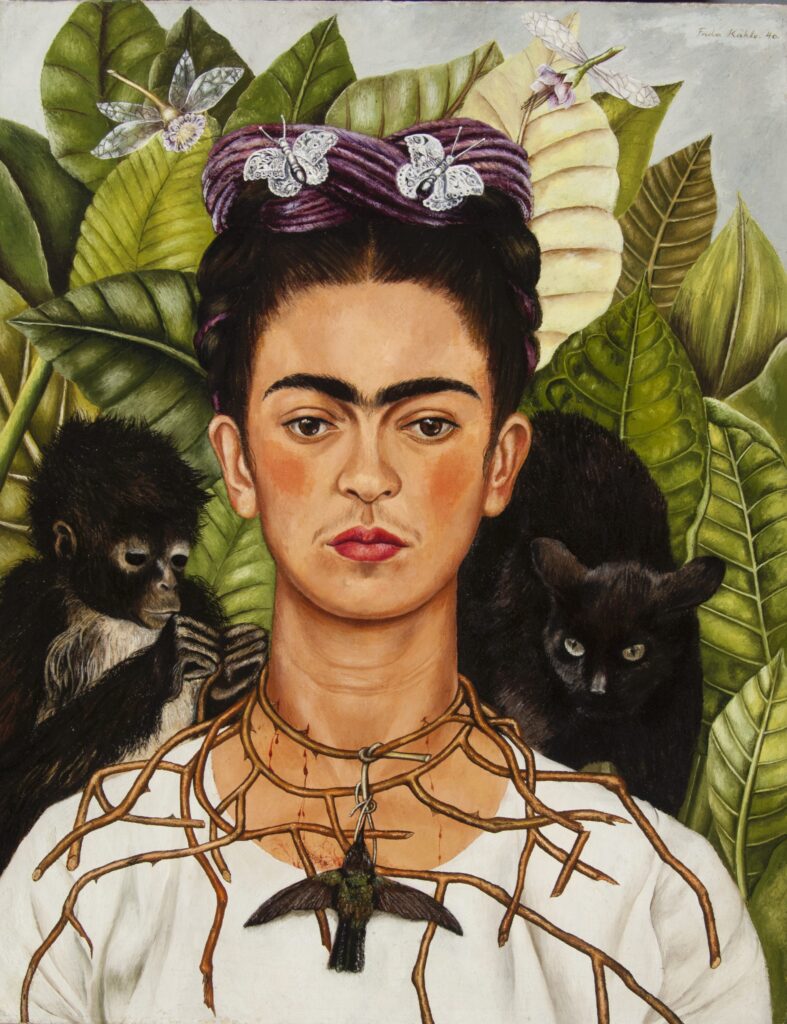

The Ransom Center is home to one of the most celebrated of Kahlo’s works: Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940). The painting has been part of the Center’s collection since 1965, when it was acquired as one of a large collection of artworks and original illustrations assembled by Nickolas Muray. Muray purchased the painting from Kahlo shortly after it was painted—and shortly after her affair with Muray and her marriage to Diego Rivera had ended. Kahlo and Rivera remarried later that year, on December 8, 1940.

One of 55 self-portraits Kahlo created in her lifetime, the painting is frequently on display in our lobby when it is not being shared with audiences around the world as the Center’s most frequently loaned work. The Center also holds two other artworks by Kahlo from Muray’s collection—the 1951 oil painting Still Life with Parrot and Fruit, and the 1930 drawing Diego y Yo. All three were featured in the 2017 Ransom Center exhibition Mexico Modern: Art, Commerce, and Cultural Exchange, 1920-1945.

When Muray’s collection was sold through a New York bookseller in 1965, the seller’s catalog promoted the collection’s large number of original illustrations by Miguel Covarrubias (Mexican, 1904-1957). That it also includes works by such members of Muray’s circle as Rafael Navarro, Rufino Tamayo, and Frida Kahlo—named in the catalog as “Diego Rivera’s wife”—was secondary. References to “Madame Diego Rivera” had been common in the US since Kahlo’s first New York exhibition in 1938. Given that the sale was being organized by a bookseller, the greater interest in Covarrubias’s important original illustrations is perhaps unsurprising; nevertheless, reading the sales description today demonstrates how enthusiasm for Kahlo has skyrocketed in recent decades. Now, one would not be surprised to hear Diego Rivera identified as “Frida Kahlo’s husband.”

Kahlo’s works are rich in their availability for multiple readings and have been interpreted in a number of ways. In the past two years alone, Self-Portrait has been prominently featured in three major—and very different—exhibitions. In 2018, together with Still Life with Parrot and Fruit, the painting traveled to MUDEC in Milan, where it was featured as part of Frida Kahlo: Beyond the Myth. For this exhibition, which highlighted Kahlo’s personal struggles and resilience and how these impacted her work, the paintings were exhibited alongside a large number of Kahlo’s other artworks, as well as letters and photographs of the artist, her disability aids, and the places in which she lived and worked. In 2019, both paintings were part of the MFA Boston’s Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular, which focused on Kahlo’s engagements with art and objects that were hand-made in Mexico’s rural communities. Currently, Self-Portrait is on loan to the Schirn Museum in Frankfurt, Germany as part of Fantastic Women: Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo, where Kahlo is presented as part of a large, international network of women Surrealists.

![Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954),Untitled [Still life with parrot and fruit], 1951. Oil on canvas, 25.7 x 28.2 cm.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2020/06/KahloF_Still_Life_Condition_Photos_001-1024x912.jpg)

As demonstrated at the Schirn, Kahlo’s works share a resonance with many of those of her female contemporaries, such as Louise Bourgeois, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington, in that they blur the lines between interior and exterior, the unconscious and the conscious, and the natural, spiritual, and bodily realms. But although her work was acclaimed by French Surrealist André Breton in the 1930s, Kahlo herself resisted this labeling of her artworks. Her works can also be seen as unorthodox retablos, as negotiations of identity, as statements of political belief, and as examples of artistic self-mythologizing.

In Self-Portrait, the animals, foliage and floral elements, thorn necklace, and Kahlo’s clothes and hairstyle have been interpreted variously as symbols of hope and love, of death and evil, of indigenous Mexican culture, of Christian martyrdom and resurrection, of fertility, and as references to Diego Rivera and to Kahlo’s Casa Azul garden. Taken together with her other self-portraits, Kahlo creates an identity on the canvas that is fractured and fluid but resolute, fragile, perhaps, but confident and self-aware. In both her paintings and her biography the viewer can identify the highly personal and intimate, the culturally and politically specific, and also the universal.

Kahlo’s public persona was carefully crafted, but—perhaps more so than with the works of many other artists—in viewing a work by Frida Kahlo we often feel that we know Frida Kahlo personally. In her depictions of love and suffering on the canvas, the viewer is stirred to feel an intimate connection with her life, her loves, and her pain, and with the explorations and presentations of her gendered, multicultural, and political identities. This connection seems so intimate that many people have come to refer to the woman who was once “Madame Diego Rivera,” and her self-portraits, simply as “Frida.”

From the Schirn Museum, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird will next travel to the Louisiana Museum in Denmark before returning to the Ransom Center in November.