During the hot summer months of 2020, especially in the weeks following the May 25th killing of George Floyd while in police custody, the Magnum Photos, Inc. Photography Collection was often on my mind. The scenes of protest that we witnessed, in countless cities across the United States and the world, reminded me of the iconic Civil Rights Movement images that Magnum’s photographers created. Burt Glinn in 1957 Little Rock, Eve Arnold at the 1961 Black Muslim rally, Danny Lyon at 1963 SNCC sit-ins, Leonard Freed at the 1963 March on Washington, Bruce Davidson at the 1965 Selma march: These images, and many more, documented the epic Black struggle to achieve greater social justice, a struggle that so obviously continues.

The value of these historical images is immeasurable; they help form the raw material of the Civil Rights Movement’s historical memory. Perhaps that’s why these photographs—taken more than a half century ago—also seem to be from another world. Between then, an era defined by legal segregation and voter suppression, and our own moment of protest against police violence and systemic racism, are the images of another Magnum photographer, Eli Reed. And it is to his work that I’ve turned—especially his ongoing, self-assigned project, Black in America—to provide visual context to what we were seeing on the streets of Minneapolis and beyond.

My personal journey on this long road has been a meditation about what it means to be a human being.

—ELI REED

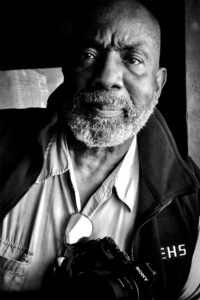

Reed has been with Magnum since 1983, becoming a full member in 1988. He joined the faculty of The University of Texas at Austin as a clinical professor of photojournalism in 2005, when we first met. An accomplished, award-winning photojournalist, Reed has covered world news events for leading publications such as The New York Times, Newsweek, The Washington Post, Time, Stern, and many more. His documentation of life and conflicts in Central America, the Middle East, and Africa is especially well known, as is his work as a still photographer for major motion pictures. “My personal journey on this long road has been a meditation about what it means to be a human being,” he writes in the preface to his recent retrospective publication, A Long Walk Home. “I have tried to capture the complicated beauty and reality of life in a visual form.”

It is often noted that Reed was the first Black photographer to become a member of Magnum. “By signing him on,” Gordon Parks observed, “the agency granted loftiness to its own existence.” Parks was right, of course. What Reed brought to Magnum was not just diversity in the agency’s labor pool, but a perspective that helped him make photographs unlike those of his white peers. This may have been welcome within Magnum (Reed counts many of its members as his closest friends and mentors), but the publishing world sometimes balked. “You’re too close to the subject,” he often heard from magazine editors when he approached them with photographs of Black life—a perception that reflected the structural racism that Reed encountered throughout his career.

“White people don’t know the biases that surround Black people all the time,” he recently told me as he reflected on that racism. With words that echo the sentiment of civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, he said “I’m tired of being tired from it all.” In this way, Reed empathizes with many of his photographic subjects, and in doing so bestows upon them a dignity and understanding that comes with many shared experiences. Reed’s humane empathy is fueled by an anger about the injustice that he witnessed. “His soul, firmly locked into black problems, fuels his indignation, compels his eye to listen to his heart,” Parks found in his protégé’s work. Deploying a metaphor that Parks used for himself, he noted that, for Reed, “his camera becomes a weapon against hardships black people war against every day.”

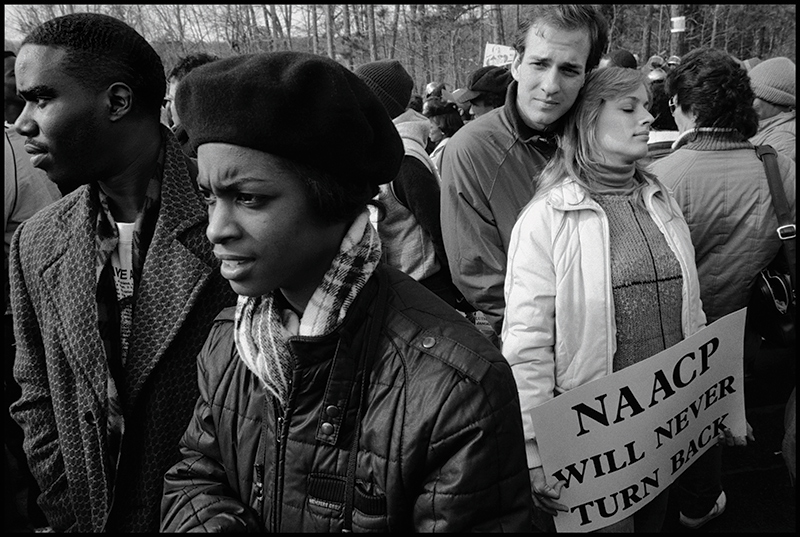

That activist impulse is present throughout Black in America, published by W. W. Norton in 1997, a good portion of which is available in the recently housed Magnum Photos, Inc. Photography Collection at the Ransom Center. One sees it, for example, in the photograph of two couples, one Black and one white, at the 1987 Anti-Racism march in Forsyth County, Georgia. The demonstration, which drew an estimated 12,000 to 20,000 people, was one of the largest civil rights protests since the Selma to Montgomery march, led by Martin Luther King, Jr. more than two decades earlier. The northern Georgia county was notorious for unabashed white supremacy, including its attack, one week earlier, on a small, peaceful interracial “walk for brotherhood.” In response, people from across the state and country descended on Forsyth County. Reflecting on the photograph in the context of the recent protests that have rocked cities across the nation, Reed was struck by seeing “people of all races together, extremely concerned about what is happening in the U.S. They saw in these moments… the fact that we are living in deep waters capable of drowning our collective hopes and dreams.”

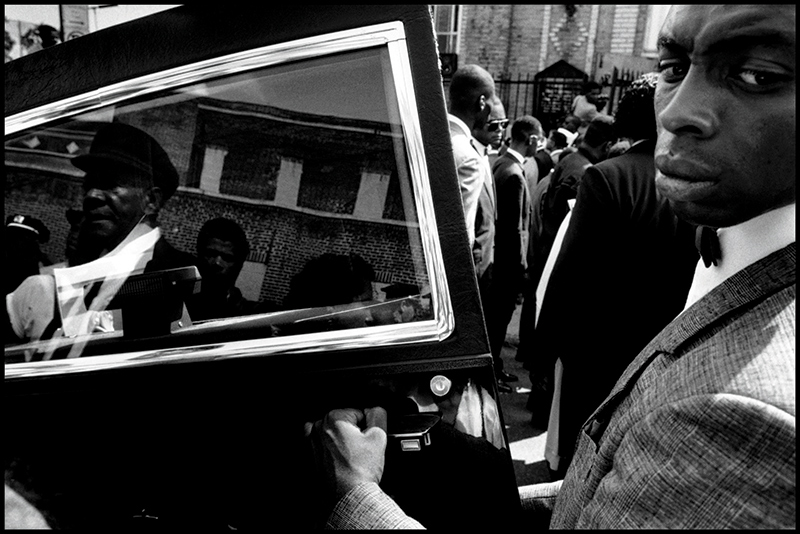

The promise of interracial solidarity should never be assumed, Reed’s photographs also show us; white-on-black violence is too deeply embedded within the nation’s DNA. Two years later, in his 1989 photograph of Yusef Hawkins’s funeral, we see the closeup of a young man’s face as he looks past the photographer. “I was as upset and angry as the man holding onto the back door of the hearse,” Reed recently said of the photograph. “I was tired of African American men basically being lynched with guns, cars, or sticks because they had black skin.” The anger shared by Reed and the unnamed young man arose from the brutal killing of Hawkins at the hands of a group of young white men and fueled the outrage that the “storm over Brooklyn” sparked across the city.

It’s not just national news events, like these or the 1995 Million Man March, that attracted Reed’s attention. A good portion of Reed’s work shows, he says, how the “fortunes of Black folk rise and fall in the quiet daily struggle for existence,” including the quiet moments of celebration and joy, like graduation from Spelman College, the historically Black liberal arts college in Atlanta. Or, take his photograph of the 1987 Harlem street scene, with children playing on an abandoned car. It’s easy to see why the photograph has become one of his most frequently reproduced images: Youthful playfulness and defiance seem to overcome the neighborhood’s poverty. It’s the kind of image that I believe Reed anticipated would move his project forward, one in which he hoped “would form an inspiring overview of one chapter in our struggle for equality in America.”

Few photographs, to my eye, are more inspiring than Reed’s 1984 picture of the groom and ring bearer in Beaufort, South Carolina. The look, as Reed puts it, of “unabashed admiration” on the little boy’s face makes it seem as though he “was gently being given lessons from life directly to his little heart.” And what are those lessons? Most surely, that racism runs through the course of America’s veins, but also that justice sometimes prevails. One would never come to that conclusion by simply looking at the photograph, of course, or by reading its minimal caption. But when one learns that the groom is Lenell Geter, who, as a 25-year-old aerospace engineer, was falsely charged two years earlier for a petty crime that he did not commit, the photograph takes on deeper meaning. Geter’s conviction by an all-white jury in Greenville, Texas, led to his sentencing of life in prison. His conviction was overturned, but only after the NAACP took up the case and national media pressured local authorities to review the evidence for his innocence.

His soul, firmly locked into black problems, fuels his indignation, compels his eye to listen to his heart,” Parks found in his protégé’s work. Deploying a metaphor that Parks used for himself, he noted that, for Reed, “his camera becomes a weapon against hardships black people war against every day.

—GORDON PARKS

Reed finds that the hope expressed early in his project has diminished over the years, as he witnessed how “African Americans were still treated with the grudging tolerance that a master reserves for his servant.” But he has also not given in to despair, and it’s through his work that he tries to bring about change, a perspective that he still embodies. Thus, two weeks after George Floyd’s brutal killing, Reed attended his funeral in Houston, Texas, documenting the tremendous range of Black expressions of grief, sorrow, and anger. “In lieu of photographing Floyd,” writes Chaédria LaBouvier, “Reed’s camera tenderly captures the minutiae of people, in the middle of a pandemic, social collapse, and a revolution, willing themselves to bear witness.” Read this way, the photographs illustrate resilience and Black subjectivity. They also exemplify Reed’s belief that serious change of the sort necessary to address systemic racism does not happen overnight or without effort.

“Don’t just sit there and accept it,” Reed says. “Speak through your work. Say something.”