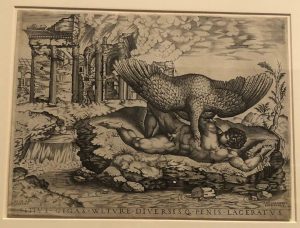

I. Artist: The artist who created this piece, The Punishment of Tityos, after the drawing by Michelangelo, circa 1542, is named Nicolas Beatrizet. According to accounts on Blanton

Museum’s website, Beatrizet was a French artist believed to be born around the year 1507 in Lunéville, France. Beatrizet moved from France to Rome, Italy, where he produced most of his artwork in his early to later life. He was well known for his artistic style of engravings. Beatrizet greatly admired and was heavily influenced by the prominent work of Michelangelo. His works inspired Beatrizet to adopt his unique style and composition. It is believed that he died after 1560, somewhere around the year 1565 in Rome, Italy.

II. Date: This engraving was created in the year 1542.

III. Location on UT Campus: The Punishment of Tityos is located in the European artwork collection in the Blanton Museum of Art.

IV. Reason for Acquisition: The Punishment of Tityos was placed in Blanton museum in 2002 when it was exhibited in the Leo Steinberg Collection. The Leo Steinberg Collection contains over 3,200 prints created by both prominent and obscure artists. The collection was brought to the museum because it is considered one of the best collections of prints and many of the the pieces have never been displayed to the public before. Many of the prints included in the collection are currently on display at the museum and greatly contribute to the character and atmosphere of the European art section in Blanton.

V. Description: The medium used to create The Punishment of Tityos is an engraving and the piece was carved on a 11 ¼ in. x 15 1/16 in. metal print. Engraving is a form of art by which an artist handles sharp metal tools to make small incisions into a metal engraving plate. The incisions resemble stroke marks and once they are made they are filled with ink to reveal a picture. This technique creates the final product called a print.

This artwork was inspired by a series of pieces that Michelangelo drew in black chalk

that depicted the myth of “The Punishment of Tityus”. The symbolic meaning behind this

painting is that actions have consequences and that indulging in your immediate desires

can bring punishment. In the case of Tityus, according to Apollodorus’ Library,

B5, the giant wanted to indulge in his lustful desire to have sex with Leto, the mother of

Artemis and Apollo. These lustful desires are a part of human nature and can’t

necessarily be prevented, however, acting upon them can. Tityus ignored his morals and

attempted to rape Leto, but was impeded by her defending children, Artemis and Apollo.

Because Tityus committed this act of hubris against Leto, Zeus condemned him to eternal

punishment in the underworld by chaining the giant to a rock and allowing vultures to

peck out his organs, only for them to regenerate. This punishment repeats itself every day

for eternity. We can translate this symbolism into our everyday lives by living with a

code of morals and not giving into in our unethical indulgences. Considering

Apollodorus’ account and Nicolas Beatrizet’s depiction of the myth, I believe the

painting symbolizes the relationship of crime and punishment.

The classical mythical elements that Beatrizet depicts in his artwork is a translation of

the story of the Punishment of Tityus. According to Apollodorus’ Library, B5,

Tityus was son of Zeus and Elare. When Zeus impregnated Elara he hid her deep within

the earth in fear that Hera, Zeus’s wife, would discover the affair. While Elare was in

hiding she gave birth to Zeus’s son, Tityus. According to Dina G. Tiniakos and the other

contributing authors to Tityus: A Forgotten Myth of Liver Regeneration, Tityus was a monstrous sized baby who had to be brought up by Gaia, mother earth. As Tityus came to adulthood, he grew into a giant. One day Tityus crossed paths with the goddess Leto and had a surge of lustful desires. Tityus gave into these indulgences and attempted to assault and rape the goddess Leto. Tiniakos notes that some other accounts of the myth suggest that this was Hera’s influence due to her nature to inflict punishment upon Zeus’ mistresses or bastard children. Nonetheless, Leto called out to her children, Apollo and Artemis, to rescue her from the giant’s assault. Artemis and Apollo attempted to kill Tityus by shooting the giant with their arrows, however, Tityus was immortal. Although the giant was not killed he was impeded in his actions and Leto was saved by her children. The giant’s immortality did not excuse punishment however, and Zeus deemed Tityus to be punished in the underworld indefinitely by in Apollodorus’ account, having his heart pecked out by vultures, and in Tiniakos’ account, his liver pecked out by vultures. However, in all accounts Tityus’ organs regenerate so the cycle repeats over and over, indefinitely.

Bibliography

Apollodorus. Apollodorus, Library . Pg. 20 B5, 1.4. (1st or 2nd c. AD, wrote in Greek)

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Tiniakos, Dina G., Apostolos Kandilis, and Stephen A. Geller. “Tityus: A Forgotten Myth of

Liver Regeneration.” Journal of Hepatology 53, no. 2 (April 27, 2010): 357-61.

doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.032.

Unknown, Author. “Artist Results.” Blanton Museum of Art Online Collections Database.

April 26, 2019.

http://collection.blantonmuseum.org/Art4533?sid=149634&x=3432252.

Unknown, Author. “Prints from the Leo Steinberg Collection, Part 1.” Blanton Museum of

Art. June 28, 2016. April 26, 2019.

https://blantonmuseum.org/exhibition/prints-from-the-leo-steinberg-collection-part-1/.

Written by Lauren Schouest

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called  Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.