The definition of what constitutes an artist’s book varies significantly depending on the social or critical circle observing the book. Is it an artist’s book, a livre d’artiste, an artist’s illustrated book, bookart, pop art, or a fine press book? If one were to look up the term and read any of the numerous essays about it, there would certainly be canonical titles offered and artists’ names as well—Henri Matisse, Ed Ruscha, and even William Blake, to name a few. Seeing these three artists of vastly different periods, styles, and mediums is proof that a single definition would not suit all audiences. In the preface in Artists’ Books: a Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, Dick Higgins writes, “There is a myriad of possibilities concerning what the artist’s book can be; the danger is that we will think of it as just this and not that. A firm definition will, by its nature, serve only to exclude many artists’ books which one would want to include.”

Although the history of artists’ books is as vigorously debated as the definition, artists’ books truly began to proliferate in the 1960s and 1970s, in particular with the idea of the “democratic multiple”—well suited to the social and political climate of the times. Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations and George Brecht’s An Anthology of Chance Operations are just a couple of examples from this period housed at the Ransom Center. Though it may be difficult to define artists’ books, often times you will know one when you see it because they can be quite unique—like a work of art. Johanna Drucker in The Century of Artists’ Books offers one distinction as “books made as direct expressions of an artist’s point of view, with the artist involved in the conception, production, and execution of the work.” A few of the more “artful” examples in the Ransom Center collection include Clair Van Vliet’s Aura and Countercode archeo-logic by Timothy Ely. Some of the characteristics present can include plates or illustrations cut from wood, linoleum, stone, or even metal; the bindings can be made of leather, wood, metal, etc.; the paper can be handmade, stitched, rolled, cut, or folded; and there is no limit to shape, size, and sometimes even sequence. Some artists’ books are even designed to be shuffled like a deck of cards and read in any order.

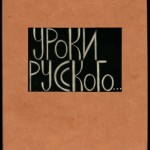

Art, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. At the Ransom Center there are numerous examples of artists’ books, ranging from Henri Matisse’s famous Jazz to Henry Miller’s heartfelt Insomnia or the Devil at Large to smaller press items like the collaboration of artist Steven Sorman with poet Lee Blessing in Lessons from the Russian. There are even a few gems in the collection that have until now escaped categorization as artists’ books. We are reviewing seminal bibliographies that address the evolving definitions of the genre and plan to revise and expand available resources to make the books in the collection more accessible. To search for artists’ books in the Ransom Center’s collections, access the UT Library Catalog: type in “artists’ books” (in quotation marks) and limit the results to the Harry Ransom Center. There is also a checklist of artists’ books available in the Ransom Center’s Reading and Viewing Rooms.

Lynne Maphies also contributed to this blog post.

Please click on thumbnails below to view larger images.