Costumes and personal effects at the Ransom Center have the potential to create a unique portrait of an author or artist, and can aid in understanding the anatomy and mechanics of an actor’s performance. Graduate intern Jenn Shapland reflects on her experience of cataloging and examining objects in the Carson McCullers collection of personal effects. Complete records and images of all items in the Carson McCullers personal effects collection can be viewed online.

It might seem funny that an author’s fashion sense would even be a topic of discussion. What does it matter what a writer wears, so long as she writes? And yet, clothes, accessories, and everyday objects give us tangible, direct links to the past and to the people who wore them, used them, and kept them in their homes.

Personal style marks writers in revealing ways: it can be suggestive of time period, class, habits, or aesthetics. I think, perhaps, it distinguishes writers more than we realize. Consider Leo Tolstoy’s tunic and beard, Gertrude Stein’s long vests and cropped hair, David Foster Wallace’s bandana, Flannery O’Connor’s cat-eye glasses. Blame it on the cult of image that surrounds all contemporary celebrities, but these visual details help bring authors to life for readers. And personal style doesn’t just bring the writing to life. It makes the writer more human and more of a character all her own.

Carson McCullers is one writer whose personal style has had an unexpected influence on me. If you perform an image search for Carson McCullers or consult one the biographies of her that houses a set of glossy photo pages in the center, you’ll see that the woman had a unique sense of style. Often it looks like she cut her own hair, in renegade fashion. Possibly with pruning shears. She wore starched white shirts with enormous collars and cufflinks. She wore so many embroidered vests. She had a face, and a stare, and a pout to end all pouts.

Many readers know McCullers for her investment in the American South, but she doesn’t write about a South that might strike you as familiar. Instead, she represents the outsiders, the misfits, the kids who don’t belong. Her writing invites you into a realm where children can befriend adults but never seem to have parents—at least not parents who are paying attention. She introduces you to adolescents who find themselves at the center of complex legacies of racial and class conflict, which they navigate with remarkable insight and open-mindedness. Their world comes alive in the heat of never-ending Augusts, while McCullers’s characters swelter in endless boredom and daydream about Alaska or snowy Cincinnati. They rarely get to leave home, but they dream constantly of a life beyond or outside the small community that is all they know.

The personal effects formerly belonging to Carson McCullers at the Ransom Center are a curious array of objects and clothing. The objects, I like to imagine, were swept straight off her desk and into a box to be mailed to the Ransom Center’s door. They feel just as random—and just as talismanic—as that. Two cigarette lighters—one gold Zippo (engraved for Terrence McNally) and one mother-of-pearl desktop lighter that weighs at least three pounds; a curious statuette of a llama (a paperweight?); a handkerchief printed with a recipe for Irish Coffee; a torn straw hat; a pair of cream wool socks, worn on the soles.

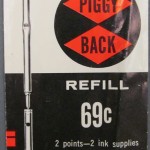

It’s hard to account for these items. When I’m cataloging artifacts of everyday existence, it’s often unlikely that I’ll find any record to confirm the role these belongings played in the author’s life. Nonetheless, the objects spark my imagination. They provide a portrait of the writer that exists nowhere else. These are the things McCullers saw, perhaps daily, the things she touched, carried in her pockets. These are Carson McCullers’s pen refills. The packaging and labeling of consumer goods also tells us something about a historical moment through design, font choices, and pricing. And the objects of everyday life ground writers in the real, tangible world; these objects help stave off the common impulse to idolize authors.

McCullers’s clothes evoke the 1940s and 1950s more than anything else in the collection. Rich tweeds in teal and lime green; a deep burgundy shawl coat that looks Russian; unfathomable long-sleeved, collared nightgowns; elaborately embroidered jackets. There’s one piece that seems especially out of place: a gold lamé jacket with magenta lining that still has the price tags on it, from all those years ago. It looks like a gift never worn; or perhaps it belonged to McCullers’s mother, Marguerite Waters Smith. Marguerite’s passport is also part of the collection; it lists her profession as “housewife” and has no stamps in it.

McCullers’s fiction comes alive through objects and through clothing, which makes her collection of personal effects that much more telling. When I think of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940), I think of Mick’s refusal to wear anything but shorts, even when she is expected to wear dresses. I think of Frankie in The Member of the Wedding (1946) and her adamant bowl cut. I picture the strange motor that she keeps on her dresser and switches on when she’s bored. Or the heinous-sounding bright orange dress she picks out for her brother’s fateful wedding. Details of objects, fashions, clothing, and garments ground McCullers’s fiction in a richer, more vibrant imaginary world, one replete with the textures of our own. McCullers brought the aesthetic of her work into her daily life with clothing and objects, and vice versa. Everyday things are an enormous part of a person’s identity; in many ways, if you think about it, they assemble who we are and what we do.

Click on the thumbnails below to view larger images.