by JESSICA S. MCDONALD

A superior volume of early photographs by the celebrated Scottish partnership of Hill & Adamson (active 1843–1847) is the subject of an unprecedented exhibition this spring. Formally titled 100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson, the volume is better known as the Clarkson Stanfield Album. Assembled in 1845, it is one of only a few unique albums produced in the years before Adamson’s death at age 26. More than 175 years later the album is undergoing structural repair, providing a rare opportunity to view several sections at once before conservators return them to the original binding. More than a collection of stunning photographs, the album provides insight into the promotional strategies employed by Hill & Adamson as they sought acceptance and patronage for their new art.

The story of Hill & Adamson’s brief partnership is now a familiar one.1 Launching their collaboration in Edinburgh in 1843, the established painter David Octavius Hill (1802–1870) and the virtuosic photographer Robert Adamson (1821–1848) combined their aesthetic sensitivity and technical brilliance to produce an unparalleled body of calotype portraits, architectural and landscapes scenes, and early social documents.

Hill & Adamson knew early on that the reproducibility of the calotype—the first negative-positive process—made it especially well suited for dissemination in books and albums. In 1844 Hill posted an advertisement in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, announcing that subscriptions were open for six thematic volumes of calotypes, produced “in a style of great elegance.”2 Because none of the proposed titles were realized, we might assume the ad generated little interest.

Turning his attention to the profitable London market in 1845, Hill called on his friends and associates to help him promote the calotype there. He explained to one important ally that the backing of “those entitled to lead in taste and in patronage” was essential to the success of the new art.3 Charles Heath Wilson (1809–1882), director of the Schools of Art at Somerset House, told Hill that he had “one friend especially who will prove an enormous puffer.”4

Hill’s good friend David Roberts (1796–1864), the acclaimed Scottish painter based in London, was their most devoted “puffer.” In early 1845, he brought a loose portfolio of Hill & Adamson’s calotypes to a Graphic Society meeting, and to a gathering at the home of Spencer Compton, 2nd Marquis of Northampton (1790–1851). Amongst the guests in attendance at Lord Northampton’s home was the distinguished English marine painter Clarkson Stanfield (1793–1867). He and Hill were already well acquainted; they were both close to David Roberts and had both been associated with the Royal Scottish Academy since 1830.5 Nevertheless, this may have been Stanfield’s first encounter with the full scope of Hill’s work with Adamson.

After the gathering, Roberts relayed the group’s enthusiastic response in a letter to Hill. Elated, Hill replied, “I cannot fail to be more than gratified by the intelligence I received from you this morning as to the manner in which the portfolio of our Calotypes had been received by yourself, by Stanfield, and the distinguished guests of Lord Northampton.”6 He confided in Roberts a new idea—he was thinking of publishing a single volume containing “a variety of Calotype subjects such as the omni[um] gatherum of the portfolio now with you.”7 He reiterated the idea two days later, telling Roberts, “I have sometimes thought of calling it ‘A Book of 100 Calotypes.’”8

Energized by the news from London, Hill must have gotten to work immediately. By October 1st, 1845, a folio entitled 100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson was in the hands of Clarkson Stanfield. It was long thought to be a “presentation album,” but we now know that Stanfield paid handsomely for it. In a letter unknown to scholars until 2020, Hill recalled that Stanfield was “one of the first men in London” to recognize his artistic contributions to photography, and that he showed his support “practically by ordering from me a volume of one hundred of my Calotypes for which he paid me 40 guineas.”9

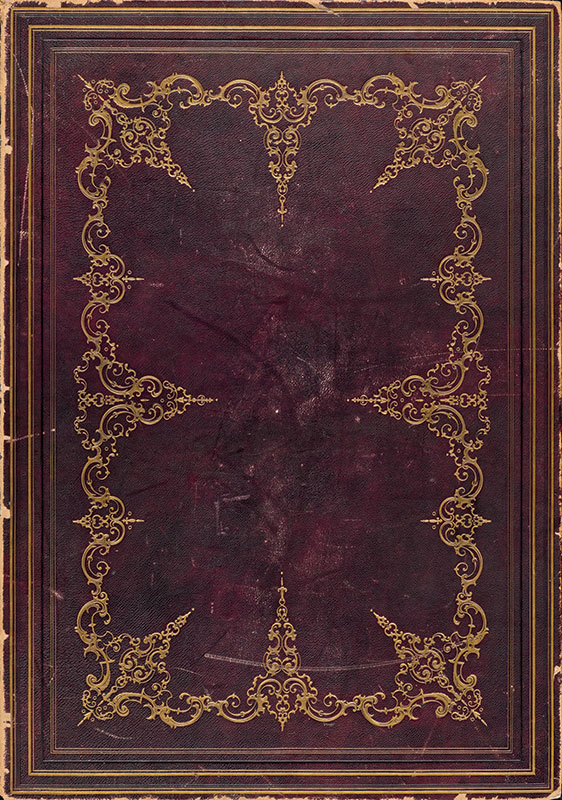

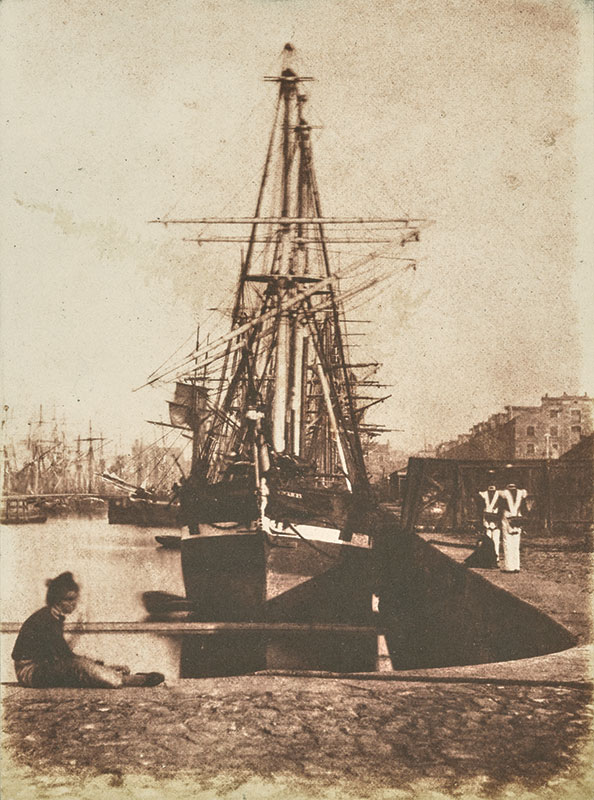

This could be the first “Book of 100 Calotypes” assembled and bound by Hill & Adamson, and it certainly set a glorious example. Hill modestly described its binding—in rich purple leather with intricate gold tooling—as “somewhat extravagant.”10 Inside the album, he and Adamson mounted a total of 103 photographs, one per page, in the style of other fine art volumes. Portraits of its authors appear first, followed by 100 plates. A photograph of the Charteris Door of Amisfield follows the plates, perhaps symbolically closing the book. As planned, the album combines subjects once proposed for separate thematic volumes, including distinguished Scots, Edinburgh architecture, and Greyfriars churchyard. Perhaps owing to the interests of its buyer, a full third of the album represents Hill & Adamson’s projected volume The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth.

Stanfield was thrilled to receive his album of calotypes on October 1, 1845. “Stayed up till nearly three o’clock looking over them,” he wrote to Hill. “They are indeed most wonderful, and I would rather have a set of them than the finest Rembrandts I ever saw.”11 Evidently Hill sent more prints in January 1846, prompting another letter from Stanfield expressing gratitude for “the promised Calotypes.”12 Stanfield likely supplemented his album with this new batch of prints; six calotypes are tipped in directly over six of Hill & Adamson’s original selections, increasing the total number of prints to 109.

In 1846, Hill & Adamson sold an album to Charles Lock Eastlake (1793–1865), the celebrated painter and Keeper of the National Gallery. Hill must have felt that by placing albums with these two influential figures, he was finally making headway in London. In April 1847, as if coming full circle, Stanfield brought his album to a meeting of the Graphic Society. A report in The Athenaeum noted “A volume of Talbotypes of a very superior description, done by D. O. Hill of Edinburgh, brought by Mr. Stanfield.”13 The same year, Sir David Brewster wrote in The North British Review that “large volumes of Talbotypes by Messrs. Adamson and Hill, at the price of £40 or £50 each,” were “now in the possession of one or two of the most distinguished artists in London.”14

Despite the efforts of Hill’s friends, interest in the Books of 100 Calotypes seems to have peaked by the time Adamson died in January 1848. As historian Sara Stevenson has concluded, “they did not succeed in moving into England, they did not gain significant patronage,” and Hill “never recouped the money he put into the partnership.”15 The collodion process soon forced the calotype—and its French competitor, the daguerreotype—into obsolescence. Hill strategically placed albums into institutional collections so that his achievements with Adamson might one day be remembered, and perhaps even celebrated.

Nearly two centuries later, Hill & Adamson are two of the most illustrious figures in the history of photography. Their body of work endures as one of the first sustained explorations of photography as an art form, and the Clarkson Stanfield Album is one of their earliest substantive compilations of key images. For students and scholars working today, it offers invaluable insight into Hill & Adamson’s ambitions for their revolutionary new medium.

Dr. Jessica S. McDonald is the Nancy Inman and Marlene Nathan Meyerson Curator of Photography.

PHOTOGRAPH AT TOP: Elizabeth Etty (1801–1888) was the niece of both celebrated English painter William Etty (1787–1849) and merchant seaman Captain Charles Etty (1793–1856). Miss Etty didn’t share the fame of her uncles, yet her elegant portrait conveys a sense of quiet confidence before the camera.

NOTES

1 See, for example, Sara Stevenson, The Personal Art of David Octavius Hill (Newhaven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), and Anne M. Lyden, A Perfect Chemistry: Photographs by Hill & Adamson (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2017).

2 Advertisement, Edinburgh Evening Courant, 3 August 1844. Reproduced in Sara Stevenson, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson: Catalogue of their Calotypes Taken Between 1843 and 1847 in the Collection of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1981), 11.

3 D. O. Hill to David Roberts, 12 March 1845. Quoted in Sara Stevenson and John Ward, Printed Light: The Scientific Art of William Henry Fox Talbot and David Octavius Hill with Robert Adamson (Edinburgh: H.M.S.O. in association with the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1986), 37.

4 Charles Heath Wilson to D. O. Hill, April 1845. Quoted in Stevenson, The Personal Art of David Octavius Hill, 18.

5 Hill was Secretary; Stanfield was an Honorary Member.

6 D. O. Hill to David Roberts, 14 March 1845. Quoted in Stevenson, Printed Light, 38.

6 D. O. Hill to David Roberts, 12 March 1845. Quoted in Stevenson, Printed Light, 38.

8 D. O. Hill to David Roberts, 14 March 1845. Quoted in Stevenson, Printed Light, 38.

9 D. O. Hill to Edward Walford, 25 January 1862. Emphasis Hill’s. Private collection, Edinburgh. Transcription kindly provided to the author by Sara Stevenson.

10 D. O. Hill to John Scott of P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. Quoted in Colin Ford, ed., An Early Victorian Album: The Photographic Masterpieces (1843–1847) of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson (New York: Knopf, 1976), 39.

11 Clarkson Stanfield to D. O. Hill, between 1 October and 13 November 1845. Quoted in Calotypes by D. O. Hill and R. Adamson Illustrating an Early Stage in the Development of Photography, Selected from His Collection by Andrew Elliot (Edinburgh: privately printed, 1928), 6.

12 Clarkson Stanfield to D. O. Hill, 23 January 1846. Royal Scottish Academy manuscript collection. Transcription kindly provided to the author by Sara Stevenson.

13 “Fine Art Gossip,” The Athenaeum, no. 1017, 24 April 1847, 440. The terms Talbotype and Calotype were interchangeable.

14 [Sir David Brewster], “Photography,” North British Review 7, no. 14 (August 1847): 479.

15 Sara Stevenson, “Cold Buckets of Ignorant Criticism: Qualified Success in the Partnership of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson,” The Photographic Collector 4, no. 3 (1983): 341.

CREDITS

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), Miss Etty, 1844. Salted paper print, 21 x 14.6 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0037.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), 100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson (Edinburgh, 1845), front cover. Gernsheim Collection, f TR 395 H553 HRC-P (964:0048:0001–0109.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), At Roslin, 1843–1845. Salted paper print, 16.4 x 11.5 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0104.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), Newhaven, 1843. Salted paper print, 14.7 x 20.1 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0092.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), [Fishermen and Boys, Newhaven], 1843–1845. Salted paper print, 14.9 x 20.1 cm. Gernsheim Collection, purchase, 964:0048:0091.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), Leith Docks, 1843–1845. Salted paper print, 19.8 x 14.6 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0059.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), Edinburgh Castle from the Greyfriars, 1843–1845. Salted paper print, 11.6 x 15.9 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0056.

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843–1847), Miss Etty, 1844. Salted paper print, 21 x 14.6 cm. Gernsheim Collection, 964:0048:0037.