Helen Macdonald is the author of H is for Hawk (Grove Atlantic), out this month in paperback. H is for Hawk landed on more than 25 book of the year lists and was an instant New York Times bestseller. Macdonald, a falconer and naturalist, writes about training a goshawk as a challenge to herself that helped while she grieved for her late father. To research her book, she visited the Ransom Center and accessed the archive of outdoorsman and novelist T. H. White, who wrote of a similar attempt.

H is For Hawk leads the reader through a series of personal archives: your own memories, your father’s photographs and notebooks, and T. H. White’s published work, diaries, and correspondence. How did your background as a scholar and historian contribute to your writing process?

H is For Hawk leads the reader through a series of personal archives: your own memories, your father’s photographs and notebooks, and T. H. White’s published work, diaries, and correspondence. How did your background as a scholar and historian contribute to your writing process?

I don’t think I would have attempted a book like this without having spent all those years in academia. Even so, I didn’t know whether I could make it work. Trying to keep all the different sources in play, setting them with and against each other: that was a fascinating formal challenge. Also, archives can be daunting, particularly when you’re faced with a vast wealth of material, and previous experience dealing with historical source material was helpful for me. I wanted to do something different from my academic work, though; make the book far more reflexive, making it obvious that my own (grief-inflected) thoughts were being brought to bear on matters historical and biographical. As for the process of writing? Well, I wrote the book in consecutive chapters, editing it fiercely as I went along. That’s how I do it, not necessarily how it should be done. Everyone has different strategies. Some things had to fall out of the book; sections, paragraphs, thoughts, sometimes whole chapters that didn’t fit. I think that being at peace with losing weeks of hard work each time I deleted sections that weren’t doing enough to remain in the manuscript—that too was something I’ve learned over years of being in academia. It’s still hard, though.

Those of us working in archival institutions often witness that instantly recognizable “archival glow” on the face of a scholar making a new discovery or connection. What discoveries did you make in your own research? Were there watershed moments that moved the project in a new direction?

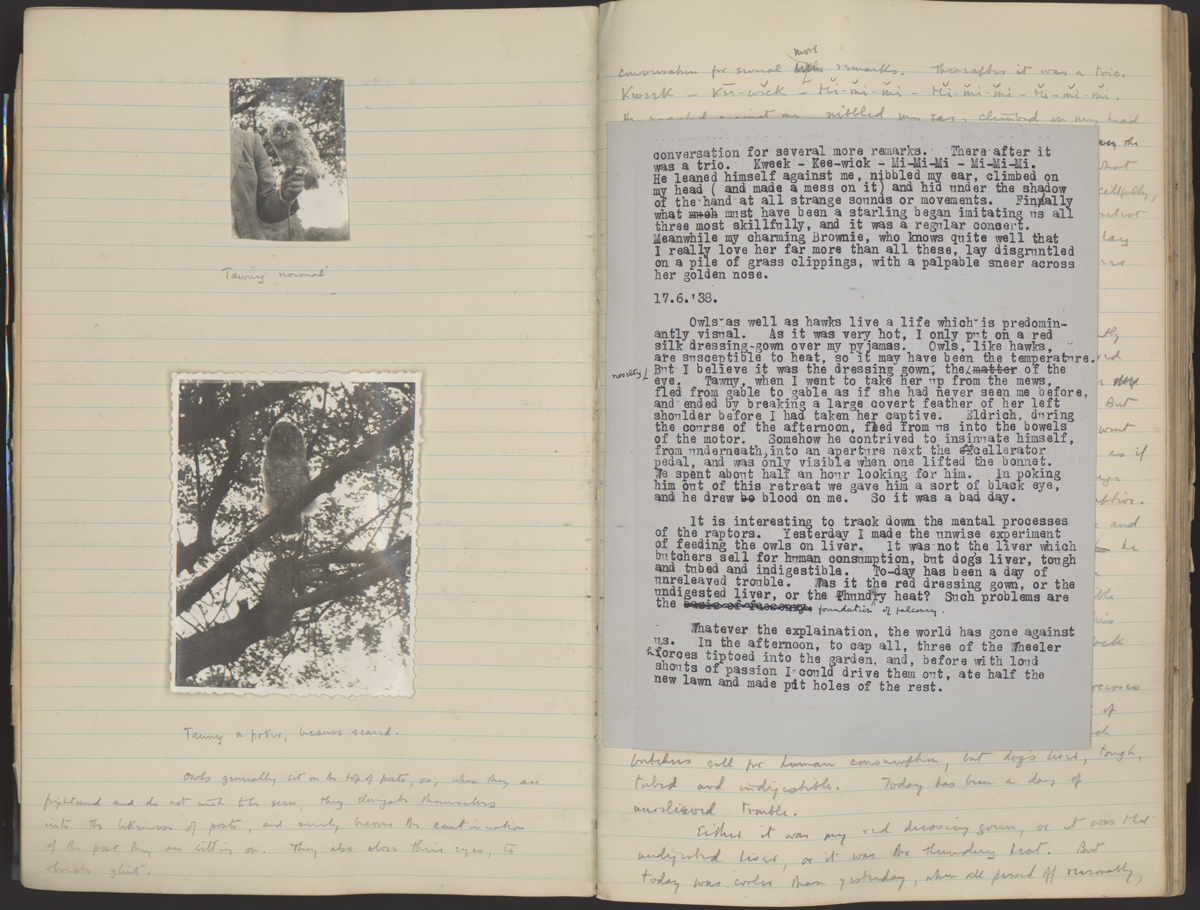

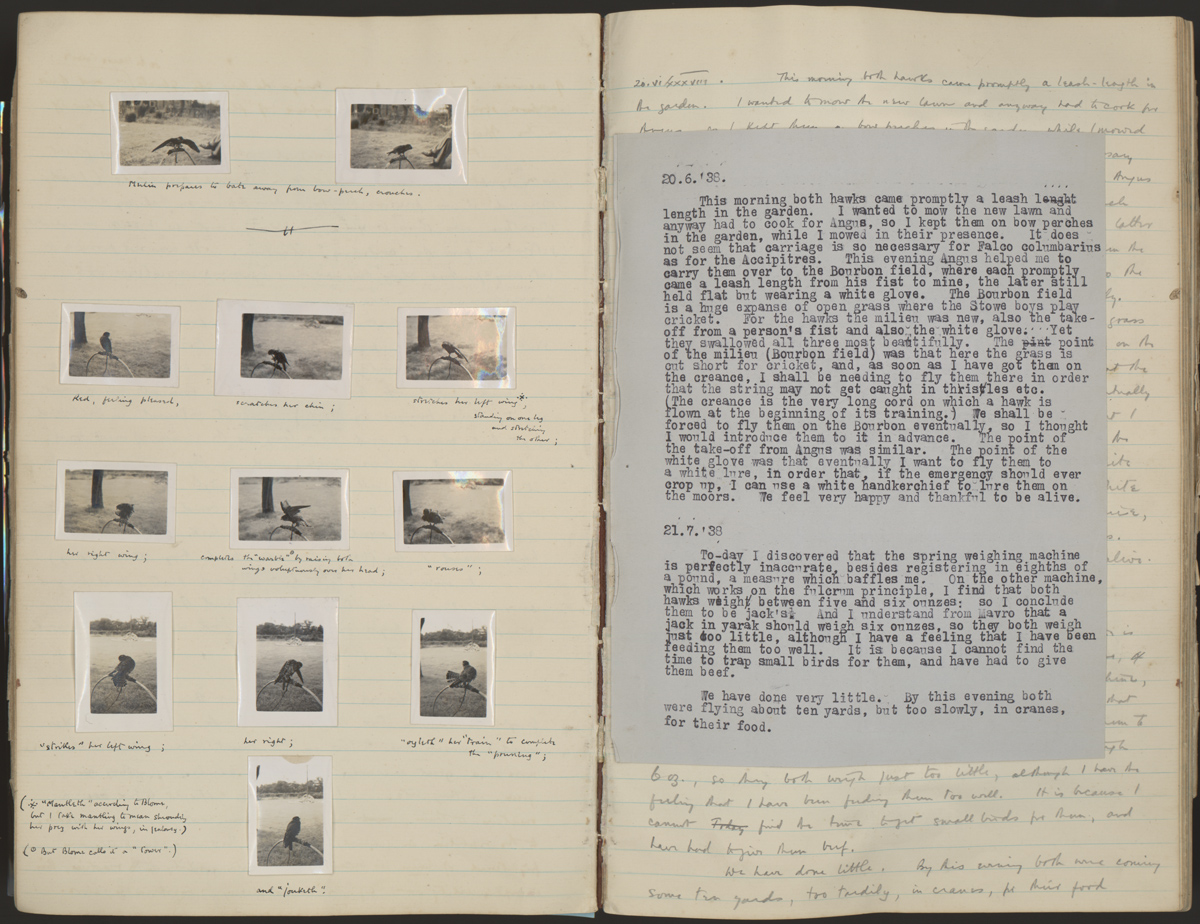

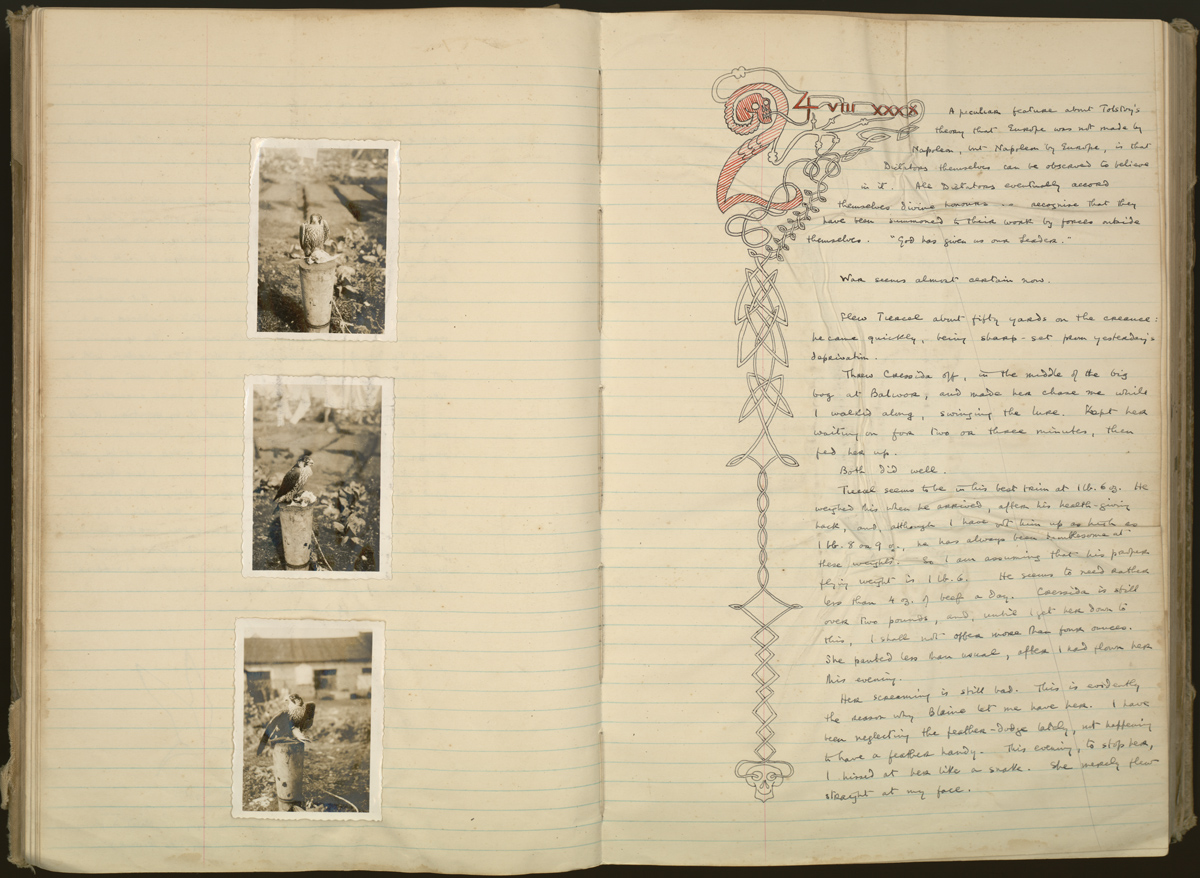

Having the opportunity to work through the archival holdings relating to T. H. White was a joy. I didn’t know quite what to expect and I had limited time to conduct my research. But luckily, his handwriting is extremely clear and he is a fantastically candid writer, particularly in his diaries. We are prone to all kinds of self-delusions and fictions about ourselves and our own lives and I guess it’s this, in White’s case, that makes his unpublished writings profoundly poignant to read. I discovered so many different selves there: his flowery, poetic undergraduate letters, his exacting, expert persona as he wrote of hunting and shooting and fishing. Apart from the opportunity to read unpublished manuscripts like “You Can’t Keep A Good Man Down,” it was fascinating to see how books like The Goshawk and England Have My Bones were constructed; much was copied almost word-for-word from his writing notebooks and sporting diaries. The moment I think that gave me most pause was when I came across a few entries in the journals that had been written in pencil and extremely carefully erased. I spent a lot of time trying to decipher the missing text from the indentations and faint graphite shadows on the page, half-expecting them to be something truly morally vile. And it turned out these were confessions that he had masturbated. It’s moments like this that are able to give you powerful insights not just into the emotional economies of your subjects, but the strangeness of that past world they inhabited.

You had a great line in an interview with Steve Paulson about being transported by the experience of reading T. H. White’s notebooks in the Ransom Center, feeling the wet English winters even on a 90-degree day in Austin, Texas. Why do you think this experience was so visceral?

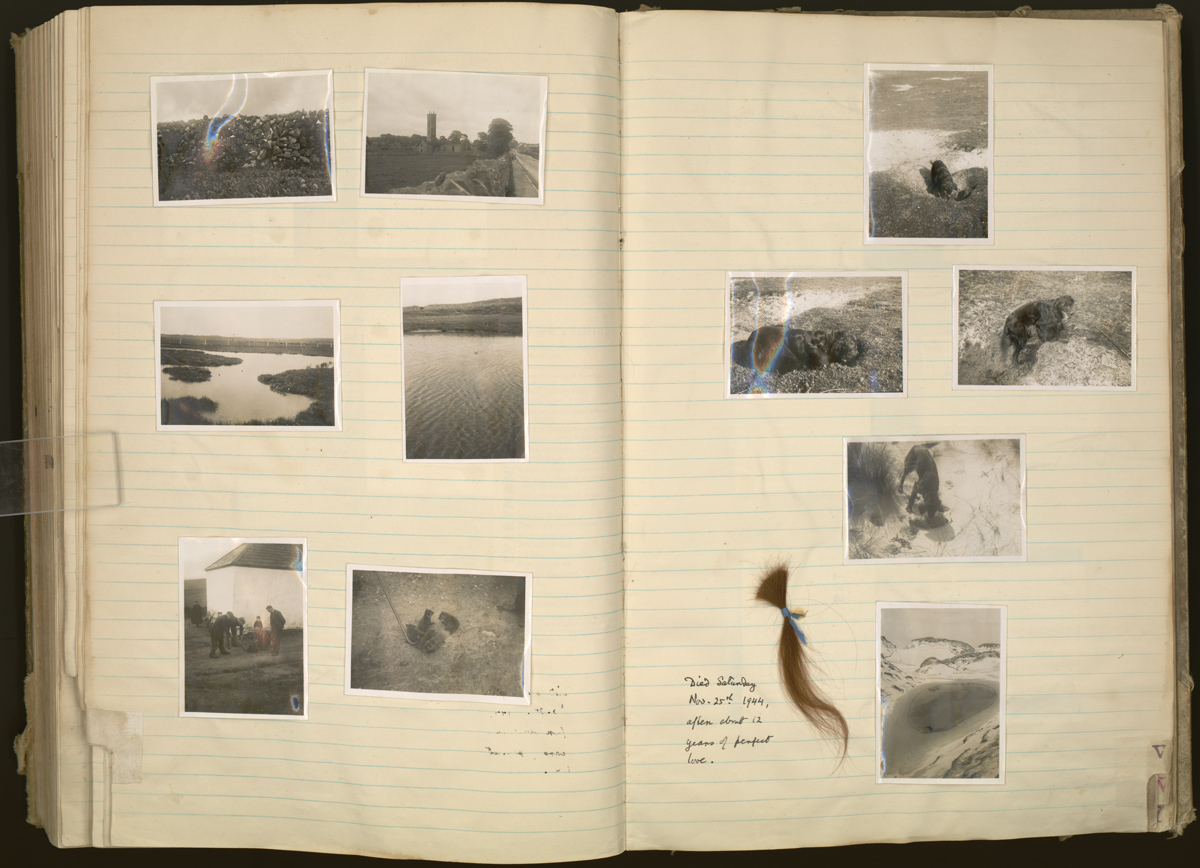

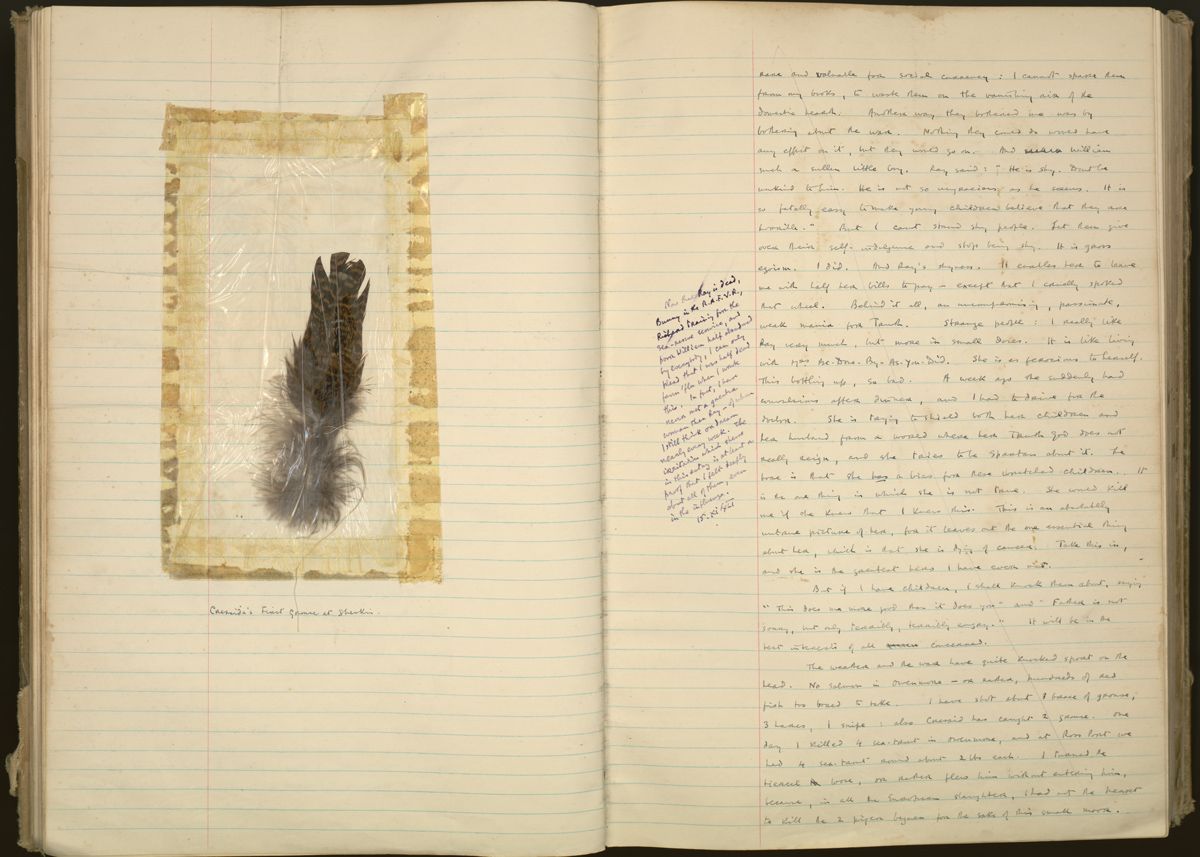

It was a very odd feeling. The vast and humid heat outside while I sat at a desk and read about salmon fishing under grey Irish skies, goose-shooting on the frozen Norfolk coast, training a goshawk at night, dew heavy on the English grass outside. The form White’s diaries take contributed hugely to this sense of being transported. They are full of material goods. Some are decorated with complicated doodles and drawings, and they are packed with photographs, tipped-in news cuttings, feathers, postcards, even a skylark claw from the first skylark his merlin killed. The most affecting of all, I think, is a lock of hair from Brownie, his beloved Irish Setter. He cut it from her after she died and stuck it to the page, tied with a red ribbon, and it’s as bright as if it happened yesterday. I think there were tear-spots, too, on that page, still visible. If you spend a lot of time working on a particular individual you do start to be haunted by them. It’s almost inevitable. I don’t think White haunts me so much these days, but recently I was invited to Stowe to meet members of the family who knew him—they are lovely—and had the opportunity of visiting his old house, where the events in The Goshawk took place. It’s not changed much. The strangest thing was that the house felt like a distant, real memory. I felt I’d already been inside it. That’s how powerful the effect of reading his diaries and journals and books was on me.

How would you say your research in the Harry Ransom Center contributed to the book as a whole?

T. H. White was always going to be in H is for Hawk. It was his 1951 work The Goshawk that unconsciously spurred my desire to train a hawk after my father’s death. Both he and I flew to hawks as a way to escape ourselves and our personal demons. I’d read The Goshawk many times, along with Sylvia Townsend Warner’s magisterial biography of White. But it wasn’t until reading his papers at the Harry Ransom Center that I realised he was going to have a much larger role in the book—that his story was not only heartbreaking, but hugely instructive. I don’t think he was a very likeable man. But that’s not what drew me to him. Here was a person who was never given the tools to know how to love or care for things, including himself. He’s a tragic figure, for sure, but one with the capacity for great joy, particularly in his love for the natural world, and that made him someone I could care for. I think you need to care for your subjects, if you write about them, despite your differences from them—indeed, because of your differences from them. The time I spent in the Harry Ransom Center was absolutely pivotal to how I saw White, and so the whole book. I couldn’t have written it without access to the collections.

What role can archival institutions like the Harry Ransom Center play in the creative work of aspiring writers, artists, and scholars?

A huge role. It’s not just a case of literary historical research. It’s that access to collections like these can fire new thoughts and connections and facilitate emotional, as well as critical insights into historical figures and their deeds and works. And also shed light on wider social and cultural formations from the time when they lived. And simply being there, being in the Center, sitting at tables surrounded by other writers and scholars, was a thrill. The staff were extraordinarily helpful, knowledgeable, and passionate about their work. It was a pleasure to work with them. And as I worked, I kept coming across other archival collections, papers and documents and manuscripts by other writers, and the thought that any of these could, at any moment, spur new works by new writers that say important things not only about those figures but about our own lives and times—that was an intoxicating thought.

Related content

Read more stories about T. H. White

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email. Subscribe today.