by ASH KINNEY D’HARCOURT

In the rapidly changing cultural landscape of the 1960s, the film industry explored new strategies to capture audience attention. The restrictive production code began to weaken, allowing for the emergence of the more experimental and avant-garde approaches to filmmaking that gained prominence during this decade. In film marketing, there was a discernible shift away from the traditional design elements of preceding decades that featured glamorous portraits and realism to more abstract representations of cinematic subject matter. In addition, the incorporation of vibrant color palettes, notably the distinctive use of hot pink in several of the posters showcased here, contributed to the evolution in design.

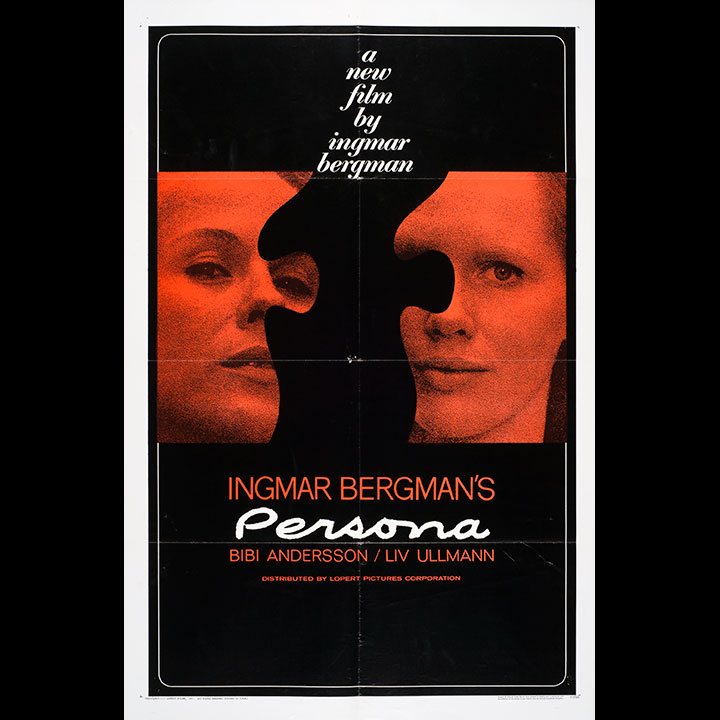

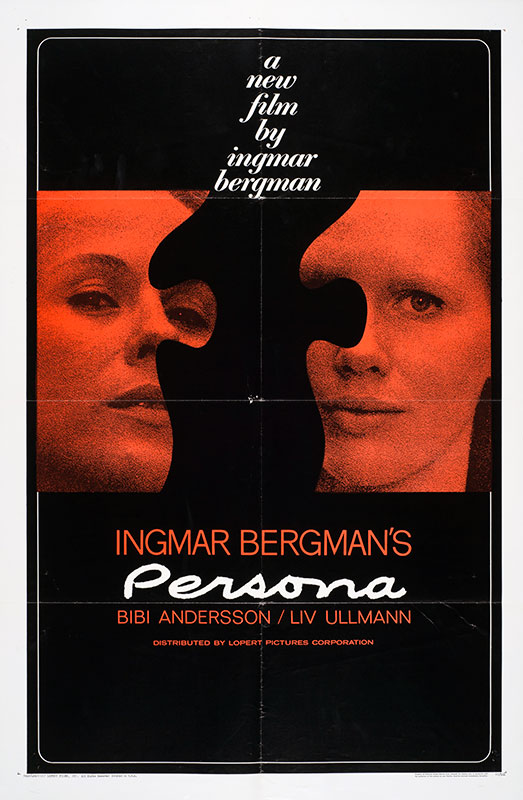

The movie poster for Ingmar Bergman’s avant-garde drama Persona (1966) encapsulates the trends prevalent in its era. The poster’s design conveys the elements of psychological horror portrayed in the film using two monochrome photographs of the leads, Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann, shaped into puzzle pieces. The artwork employs this modern and stylistic design to communicate the themes of duality and identity explored within Bergman’s film. The distinctive white typeface of the title set against an all-black background further enhances the poster’s visual impact.

In the rapidly changing cultural landscape of the 1960s, the film industry explored new strategies to capture audience attention. The restrictive production code began to weaken, allowing for the emergence of the more experimental and avant-garde approaches to filmmaking that gained prominence during this decade.

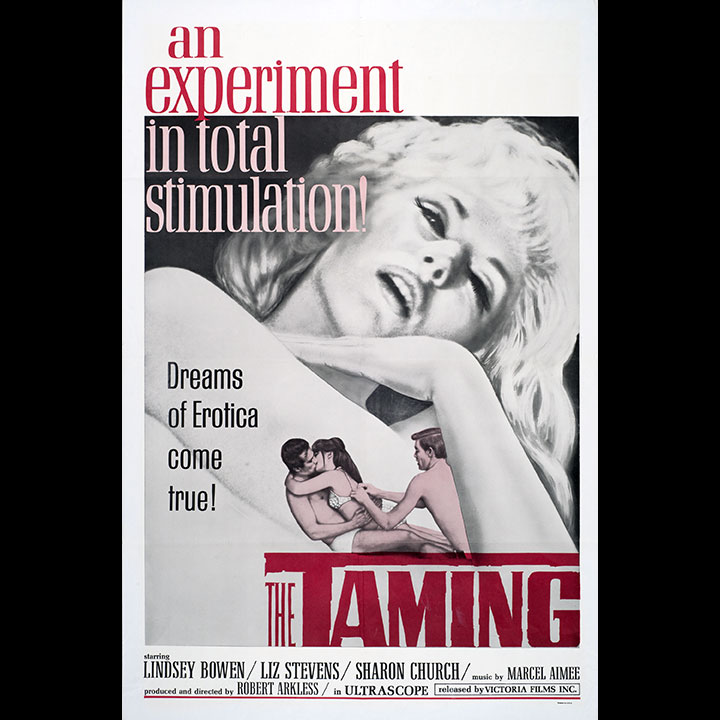

The 1960s also witnessed the beginning of the “Golden Age” of X-rated films. For example, The Taming (1968) offers a glimpse into the emerging erotic cinema that coincided with the ongoing erosion of the production code. Copies of the film itself remain elusive, rendering the poster perhaps the only surviving artifact associated with the film. A wistful review on IMDb of the film paints The Taming as a somber “black & white extremely morbid soft porn tale of loneliness, alienation and overall depression, set on a New York City subway train.” The extent of the association between the poster’s sexually suggestive imagery and the film’s content remains obscure, as the industry employed inventive, and at times misleading, strategies in the promotion of films during this decade.

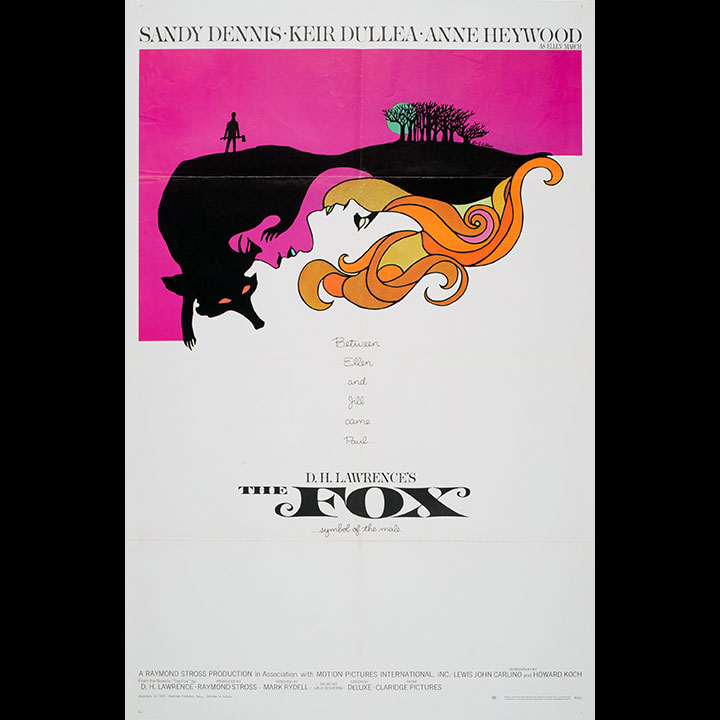

Several posters in the Center’s Movie Posters Collection serve as a gateway to the broader realm of the art world, as exemplified by the poster art for Mark Rydell’s directorial debut, The Fox (1967). Leo and Diane Dillon, a husband-and-wife artist duo known for their illustrations in science fiction, fantasy, and children’s book genres, crafted the artwork for this poster. Their portfolio also includes a series of book covers designed for author James Baldwin. The expressive color and lines of the poster create an illusion within the silhouettes that invites various interpretations. The result is a detailed and visually striking image in which the content, a lesbian-themed love triangle, remains somewhat ambiguous. The waves of saturated colors embedded in the artwork channel the psychedelic aesthetics reminiscent of Milton Glaser’s iconic 1966 Bob Dylan poster; however, owing to its delicate lines and composition akin to that of a book cover, the poster signals the film’s literary credentials as an adaptation of a novella.

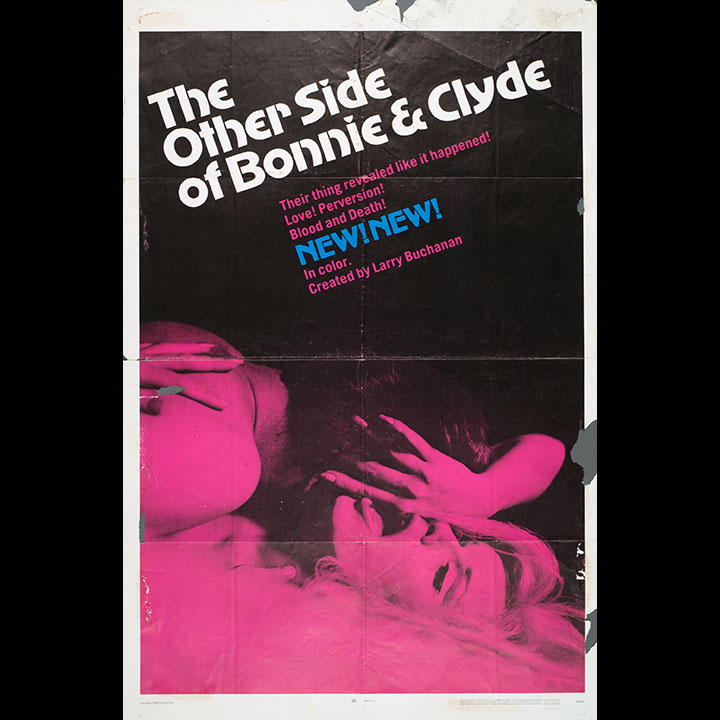

The 1968 docu-drama The Other Side of Bonnie & Clyde was released one year after the canonical noir crime film Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Harnessing the public’s interest in the criminal duo, the film was billed as the “true” story of the criminals and their ultimate demise at the hands of Texas Ranger Frank Hamer. The poster art for the film channels experimental design elements that include the titillating imagery of erotic film posters of the decade. Scholar Mary Elizabeth Strunk observes of the poster: “Bonnie’s tousled head occupies the bottom half of The Other Side’s poster. She reclines, one hand draped over her slack mouth. The image is deliberately ambiguous; Bonnie may just have been killed, or she may be about to lick her trigger finger in a moment of eroticism.” Notably, the sensationalized nature of the poster art does not accurately reflect the content of the film which itself features no explicit sexual content, again illustrating the bait-and-switch marketing techniques used to promote films during this decade.