People always want you to be born where you are. They want you to have leaped from the womb a public figure. It just doesn’t go that way. I am the composite of my experience and all the people who had something to do with it. And I’m going to try to lay that out. —Barbara Charline Jordan

In the late 1970s two women came together to tell a very Texan story. Congresswoman Barbara Jordan (1936–1996) was ready to put her life down on paper, and author Shelby Hearon (1931–2016) was ready to help her do it. The result was Barbara Jordan: A Self Portrait (1979) one of the more unusual entries in the political memoir genre. Rather than a straight biography or straight memoir, the book is something of a blend, with Hearon providing the frame and Jordan providing the narrative. Sometimes Hearon’s context and framing comes at the beginning of a chapter, sometimes at the end, or sometimes both. The book is linear, taking the reader from Jordan’s childhood through law school at Boston University School of Law, the beginnings of her local political career in Houston, and her time as the first black Southern woman elected to the House of Representatives.

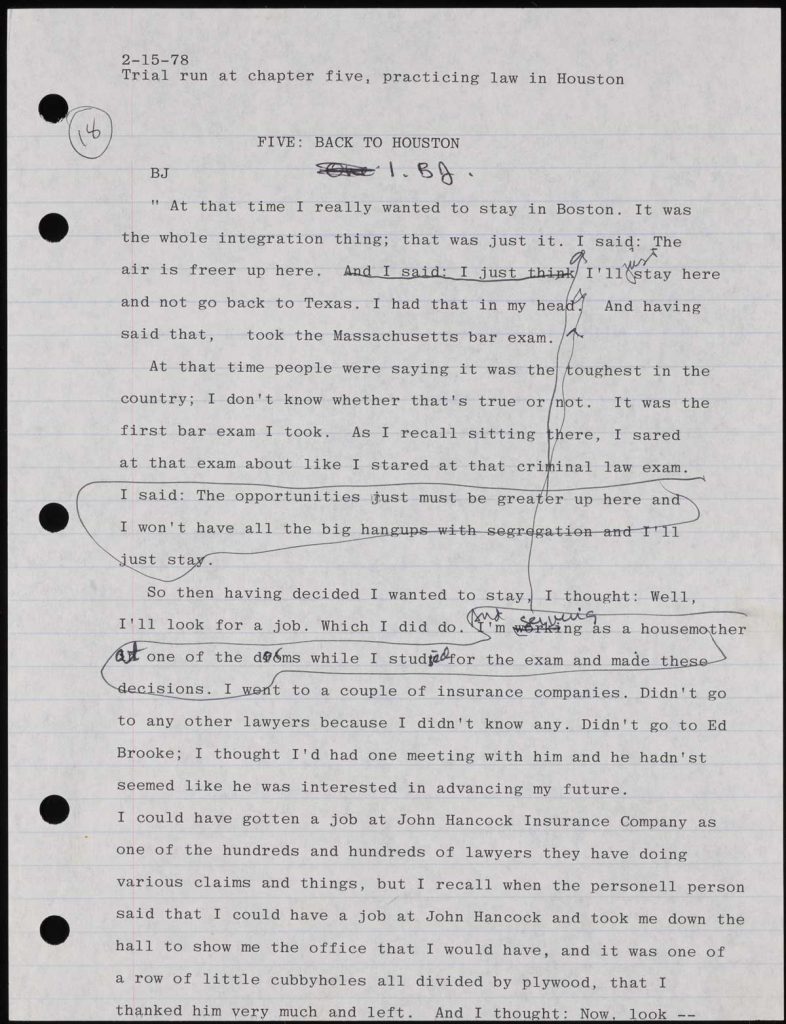

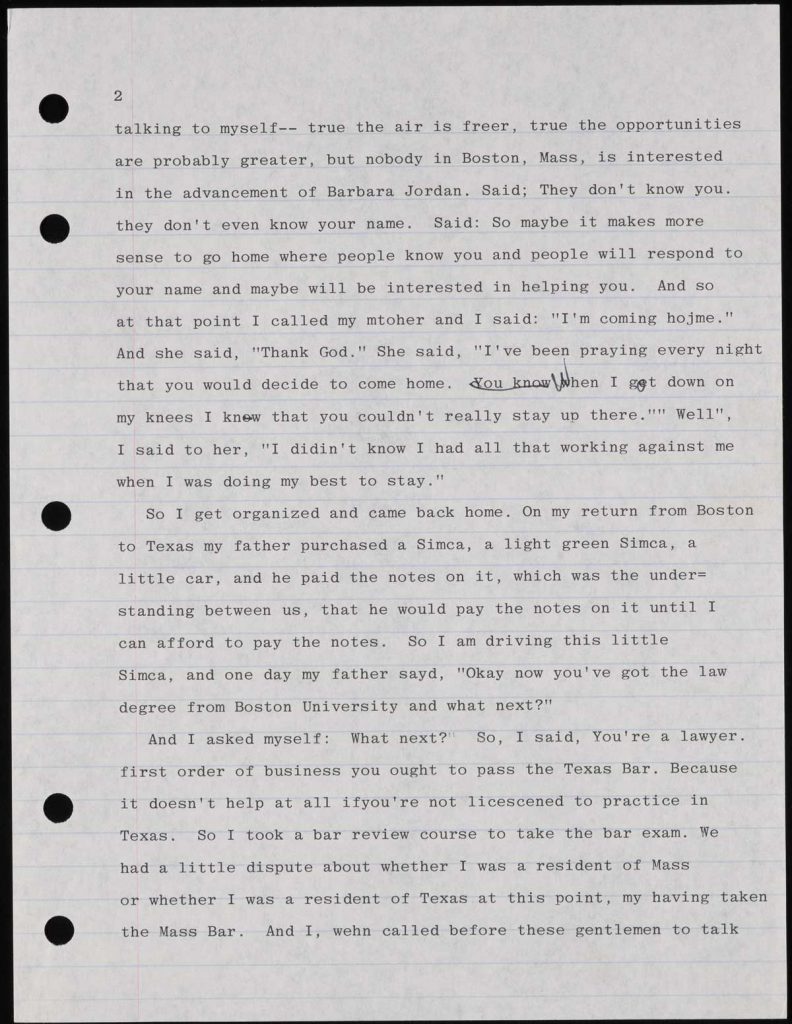

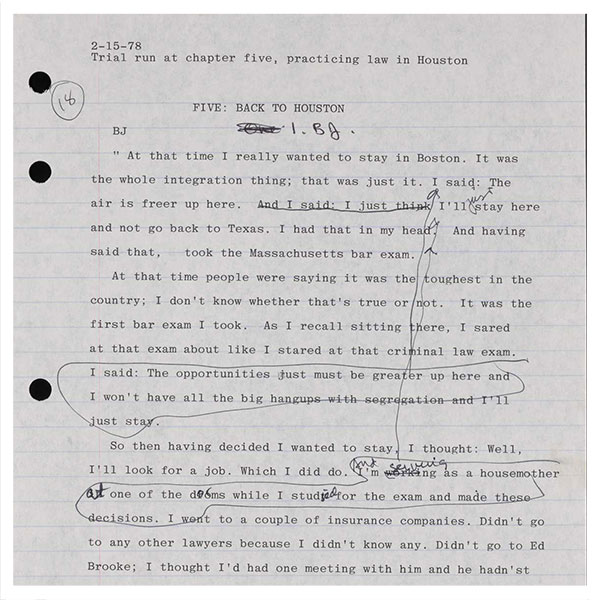

Jordan’s decision to return to Houston after graduation from law school in 1959 was not a straightforward one. She had initially intended to stay in Massachusetts. “I said: The opportunities just must be greater up here and I won’t have all the big hangups with segregation and I’ll just stay.” A visit to the John Hancock Insurance Company, where she saw that she’d be working in a tiny plywood cubicle at the end of a row of seemingly hundreds of such cubicles, changed her mind. “They don’t know you, they don’t even know your name. Said: So maybe it makes more sense to go home where people know you and people will respond to your name and maybe will be interested in helping you,” Hearon documents in her typescripts for the book.

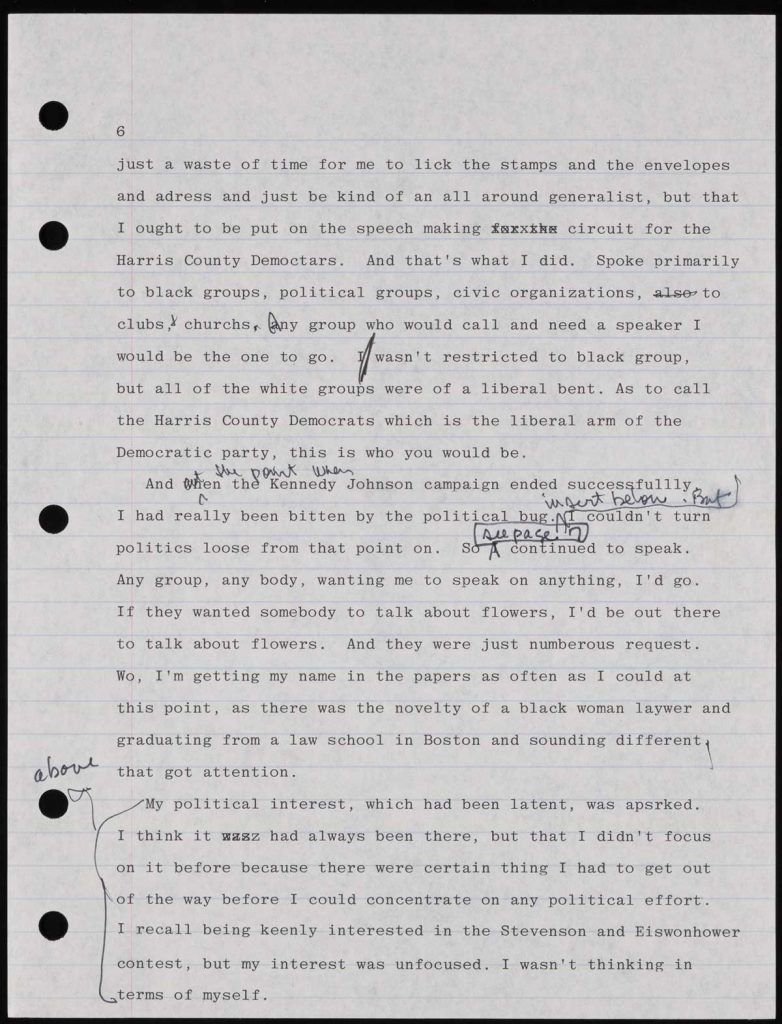

After returning to Houston, Jordan quickly joined the political scene. She began volunteering for the Kennedy/Johnson campaign organizing black voters in Harris County. Jordan’s abilities immediately became clear, and she spoke on the campaign trail locally.

After the election, she found that she couldn’t quit. “Any group, any body, wanting me to speak on anything, I’d go. If they wanted somebody to talk about flowers, I’d be out there to talk about flowers. And they were just numberous request. Wo, I’m getting my name in the papers as often as I could at this point, as there was the novelty of a black woman lawyer and graduating from a law school in Boston and sounding different, that got attention.”

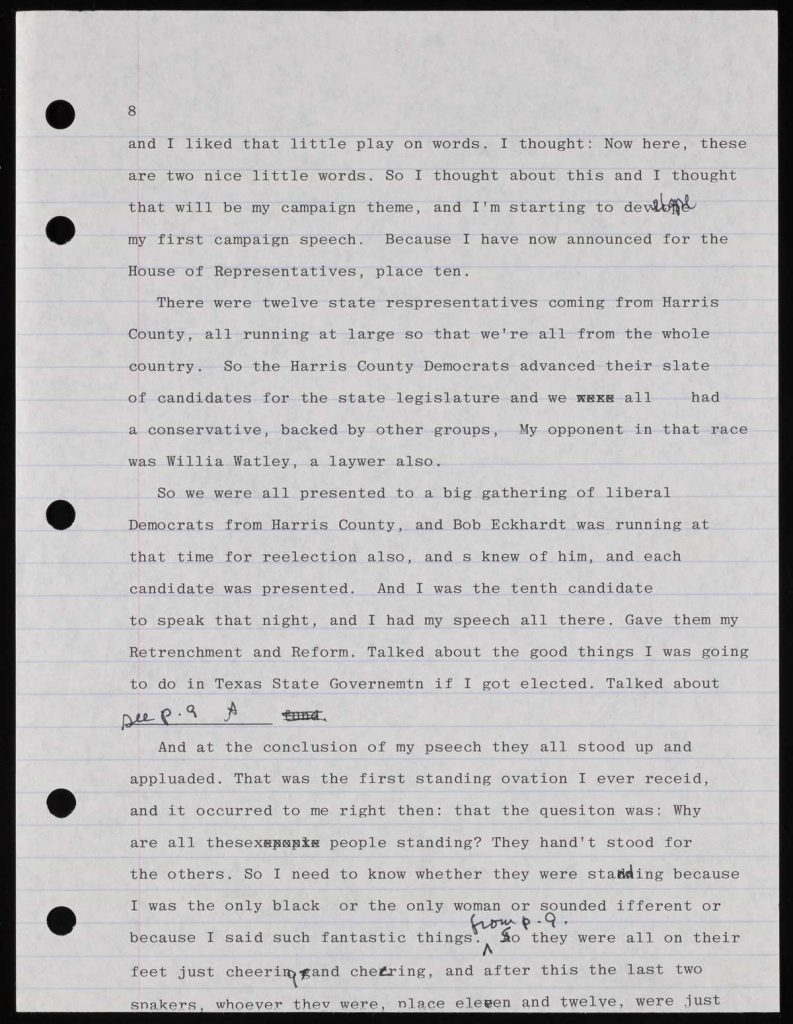

In 1962 she ran her first race, an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the Texas House of Representatives, and received her first standing ovation at a multi-candidate speaking event. “That was the first standing ovation I ever received and it occurred to me right then: that the question was: Why are all these people standing? They hadn’t stood for the others. So I need to know whether they were standing because I was the only black or the only woman or sounded different or because I said such fantastic things… I needed to know that so I could keep doing it throughout my campaign.”

After her loss, Jordan realized that she was used to bring out the black vote, but that she received no such boost in return. Nine of the 12 Democrats running alongside her were elected. All nine were white.

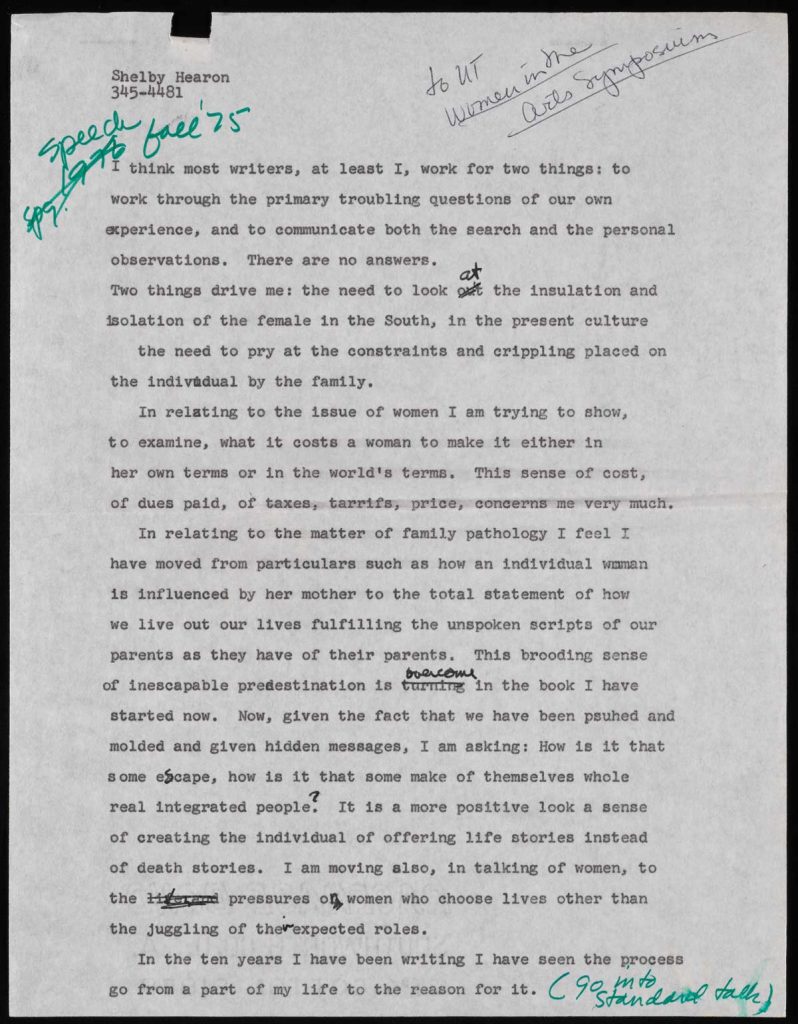

Jordan and Hearon’s pairing is a unique one—Hearon was not an obvious choice as a biographer. Born in Marion, Kentucky, but living in Texas from girlhood through the 1980s, Hearon was a novelist skilled in illuminating women’s interior lives in books such as Armadillo in the Grass (1968) and The Second Dune (1973). Hearon was an active speaker throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s as she began her second career as a writer, leaving behind a life as a housewife and PTA president.

Hearon and Jordan met in Austin in March of 1977 at the urging of friends who thought they would work well together in writing the story of Jordan’s life. As Hearon writes in the preface to Barbara Jordan, A Self-Portrait, “But we both hesitated. She, as a politician, operated from a basic distrust of writers; and I, as a novelist, from a conviction that real life is always distorted by bias, that only fiction offers the glimpse of truth.”

Ultimately, Hearon followed a structure that informed her fiction and that she returned to frequently in speeches. Jordan, in her first meeting with Hearon, asked her how she envisioned the book. “’I see it as how you got from There to Here. Everyone gets from there to here. So everyone can relate to that.’ Jordan asked ‘Do you think I’ll ever get there?’ ‘No, but I think you’ll die trying,’” Hearon relates in the book’s preface.

Women’s lives, and the sacrifices women make, are a topic Hearon returns to again and again in books like the aforementioned Armadillo in the Grass and Hug Dancing (1991). Hearon’s papers, available at the Ransom Center, trace the author’s work on her novels, short stories, and articles, as well as the speeches and lectures she gave throughout her career. In a 1975 speech to the University of Texas Women in the Arts Symposium, Hearon said, “In relating to the issue of women I am trying to show, to examine, what it costs a woman to make it either in her own terms or in the world’s terms.”

Everyone finds someone in the archives, someone whose life or work touches their own. It can be hard to articulate why. For me, that person has been Shelby Hearon. It’s not that I’ve read much of her published work. As far as writers whose papers are held at the Ransom Center, I’ve read more of Don DeLillo and Larry McMurtry than I have of her. Even so, Hearon’s biography of Barbara Jordan, her novel Hug Dancing, and her speeches from the ‘60s and ‘70s have been a throughline for my time at the Ransom Center. I’ll take Hearon’s and Jordan’s words with me, and I hope they’ll guide me in the years to come as I continue my career in the archives and in Texas—as I get from There to Here.

Shelby Hearon’s papers are at the Harry Ransom Center. Barbara Jordan’s are held in the archives of her alma mater, Texas Southern University.

Nina Tarnawsky is a graduate student in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. She worked in Digital Collections Services from February to November 2018.