by GREGORY CURTIS

The Ransom Center recently acquired the archive of a vitally important literary figure. James Magnuson is a widely respected author. He has published nine well-received novels, won awards while writing for the movies and for television, and has seen so many of his plays produced that he has lost count.

Read an excerpt from his 2014 book, Famous Writers I Have Known (W. W. Norton & Company).

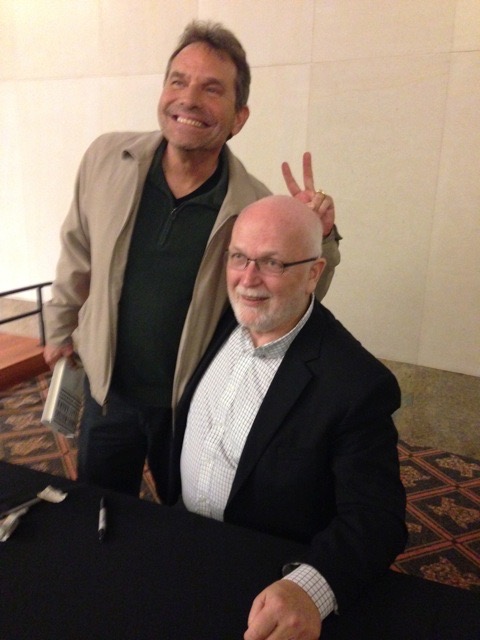

But in addition to his writing, Magnuson has held a position that both augments the importance of his archive and ensures his place in any future history of contemporary American literature. He has recently retired after 23 years as director of the James A. Michener Center for Writers at The University of Texas at Austin. During Magnuson’s long tenure he guided the Michener Center to prominence as one of a small handful of leading writing programs in the United States. The Michener Center’s importance in American literature during the last quarter of the twentieth century cannot be overstated.

It all began, as so often things do, with money. James Michener sold so many books during his long writing career that he single-handedly kept his publisher, Random House, afloat for more than 20 years. Popular as his books were, Michener got little respect or even mention from serious critics of his era. He mixed history in with his fiction so that his readers could enjoy his stories while feeling that they were learning something at the same time. Late in his career he was lured to Texas where he wrote a book called—predictably; Michener wasn’t much with titles—Texas. But Michener remained living in Austin until his death in 1997. He donated his collection of art to the University of Texas, now housed in the Blanton Museum on campus. And he began to talk to important people in the university administration and in the English department about endowing a writing program.

Jim Magnuson, 42 years old, married with two young children, broke, and living in rural Mississippi, managed to snag a job teaching writing at the university. He arrived in Austin in 1985, never having been in Texas before. Two years later an old friend contacted him out of the blue and offered him a job writing for the nighttime television soap opera Knots Landing, which had begun floundering in the ratings. Magnuson moved with his family to Los Angeles where he quickly became the workhorse of the writing staff. “I had one mantra in the story meetings,” he said later. “It gets worse. No matter how bad things are at the start of a show, it gets worse.”

Meanwhile, in Texas things started small. Michener donated $2 million to the university for a writing center. It offered lectures and attracted a few literary luminaries to the campus. Novelist Rolando Hinojosa-Smith was the director. A little while later, while the Magnusons were still in Los Angeles, Michener added another $18 million and under Joe Kruppa of the English department and David Cohen of theater and dance, plans were begun to create the Center’s own MFA program.

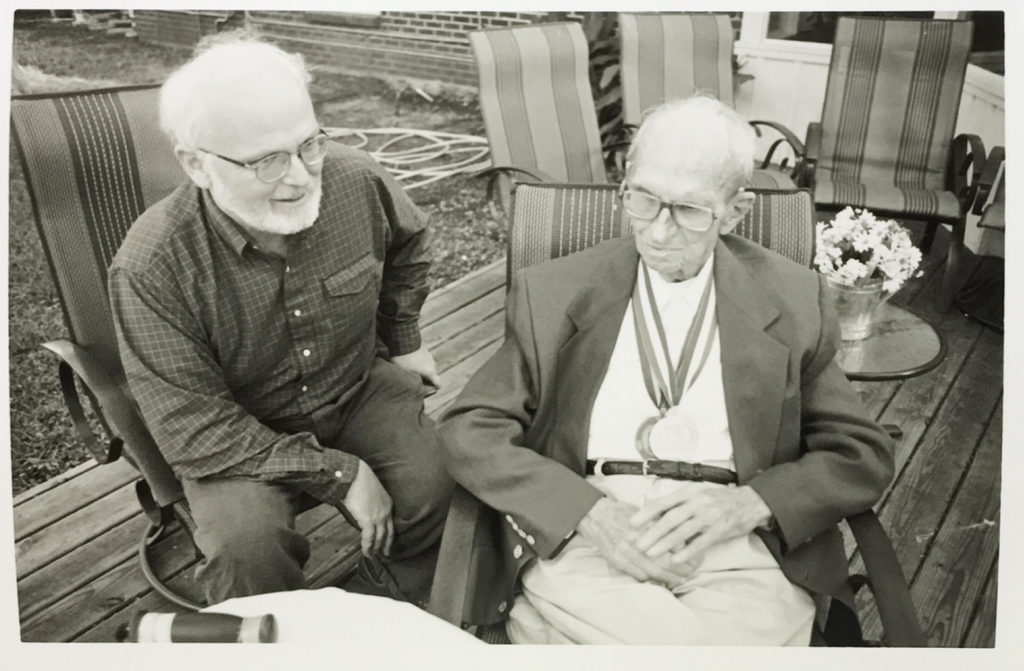

The Magnusons returned to Austin in 1992 where he participated in meetings with Michener and various important figures on the campus about what the Michener Center would be. Michener envisioned an interdisciplinary program that would teach writing fiction, poetry, plays, and screenplays. This was a revolutionary approach at the time and is still unusual. In most programs students work only in one discipline. Magnuson, however, had a varied background. After growing up in Wisconsin and graduating from the University of Wisconsin, he began writing fiction. But after moving east, he had also written plays while on a fellowship at Princeton and spent several years in New York doing street theatre in Harlem. And he had current experience in television and several of his novels were being developed as films.

Finally William Livingston, university vice president and dean of Graduate Studies, called Magnuson into his office and offered him the job as director of what eventually became called the Michener Center for Writers. Magnuson hadn’t expected this and was flabbergasted. “Bill,” Magnuson finally blurted out, “I’m working for Hollywood money now. You can’t afford me.” Magnuson was halfway joking, but he held his ground and six weeks later Livingston returned with a sweeter offer and Magnuson accepted.

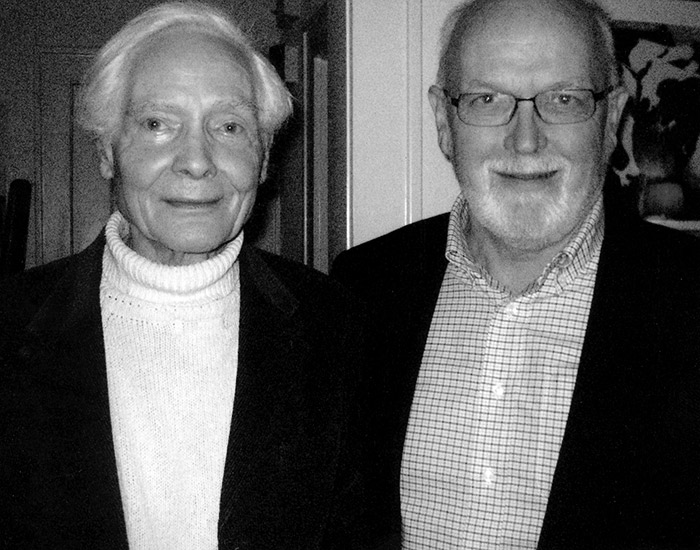

Magnuson had never thought of himself as an administrator, but now he had become one. And he had to create the process of selecting students, recruit a faculty, and work out the details of the program that the students would follow once they were in Austin. First of all he began inviting notable writers to come to Austin to work with students, sometimes for as long as a semester. Among many others, these included J. M. Coetzee, Colm Toibin, Marie Howe, Richard Ford, Geoff Dyer, and many others. Each person admitted to the program—they are known as Michener fellows—would get a large enough stipend to live on during their three years in Austin. The fellows would work together in seminars and meet privately from time to time with individual faculty. And during their time in Austin the fellows are expected to complete a novel or a play or a screenplay or a cycle of poems. The list of publications, prizes, and awards earned by Michener fellows is too long to list here but they are all available on the Center’s website. The Center began meeting in the Perry-Castañeda library, but in 1997, J. Frank Dobie’s house on Waller Creek right across the street from the law school became available. The university raised the money to buy it and the offices and meeting rooms of the Center have been there ever since.

Magnuson’s archive will be essential to anyone writing about literature in English during the first two decades of the 21st century.

Magnuson was careful to have an agreement that allowed him time for his own writing. All during his time as director he spent most mornings at a desk working longhand on legal pads. On Saturdays and Sundays he went to Dobie’s house for long hours of work alone. Still, as he approached 75, he began to worry about finishing the books he still had in mind and realized that the only way he could do so would be to resign from the Michener Center, now under the direction of Bret Anthony Johnston.

In addition to his own notes, novels, and plays—and his novels to come—Magnuson’s archives also include his notes, letters, and memorabilia that show him to be a man at the center of a literary network that extended from Austin and his office at the Michener Center to the entire English-speaking world. Just as the Center’s Norman Mailer archive, with its abundance of letters and artifacts, is essential to anyone working on the history of American literature from the 1940s to the 1980s, Magnuson’s archive will be essential to anyone writing about literature in English during the first two decades of the 21st century. Magnuson was a connector—not the only connector but an important one—of literary figures around the world. He continues to leave a legacy that will never be erased.