by JULIE HARDWICK

This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

What can a pink silk ribbon with a beadwork message JE M’ELOIGNE SANS ME’EN SEPARER (translated, “I’m going away but not leaving you”) tell us about young people’s relationships in eighteenth-century French history? As an historian, I constantly ask questions like this: looking for neglected artifacts or fragmentary texts in special collections to think about the stories they might tell.

I encountered the pink silk ribbon in 2009 in the municipal archives of Lyon, France’s second largest city. It was pinned to a “ticket” that recorded the admission of a tiny baby to the city’s foundling hospital in 1768. The ticket offered little information to provide me with research traction. The unnamed parents were poor and unmarried. The baby had been baptized, named Jean, and was two days old. A careful examination showed less immediately obvious but important clues about timing. The ticket arranging admission to the foundling hospital was dated four months before the baby’s birth. That indicated to me that the young couple had planned well ahead to resolve the problem their untimely pregnancy posed by leaving the baby at the foundling hospital.

How can we recover the stories behind an object like this? The emotional and social lives of young working people have left little in the ways of the kinds of records that survive in enormous quantities for elites. My slow research—over 15 years and two continents in archives in France and libraries in the United States—involved unravelling layers of mysteries about the cataloging, the documents themselves, and occasionally a surviving artifact tucked in between sheets of paper. Seemingly simple objects, like the ribbon, offer a window into the past: what I research and what I teach.

Objects like the pink ribbon as well as books, pamphlets, and prints are those that I share with students when I bring classes to the Harry Ransom Center. Many people know the Ransom Center for its twentieth-century literature and artistic highlights, but in my courses, my students and I routinely visit to see, at times touch, and explore the wonderful holdings of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century materials.

For instance, in my course on Witches, Workers, and Wives: gender and family in early modern Europe, we consider the relationship of gender to witchcraft and the many modern items that attest to the persistent fascination with witchcraft in the US and Europe. My students often ask questions that move beyond witchcraft to more mundane matters. Over many years their curiosity has influenced my own research and I have found answers even to questions that I used to think could not be answered. Did young single workers date? What did dating look like? Did they hook up? Why was illegitimacy so low if they were all having sex before they got married? My new book tries to answer many of these questions.

Fascinating material held at the Ransom Center attests to some of the tensions that are at the heart of young people’s relationships, and of my book, and with which my students are very familiar. “A late seventeenth- or eighteenth-century French print, “Opérateur céphalique,”” depicts a fictional blacksmith re-forging women’s severed heads to make them more malleable and pleasing wives. The scene had first appeared in an almanac in 1659, and it quickly inspired many standalone prints like the one at the Center, as well as rival illustrations where women attacked the blacksmith with his own tools. The powerful, if predictable, messaging about patriarchy and struggles against it fits perfectly into our usual paradigms of gender relations before modernity.

In contrast, the Center also holds a lovely little English playbook with an illustration that shows the ghost of a young man who had hung himself, driven to suicide by his despair over the break-up of a relationship with a young woman. This suggests a more complex dynamic. So which was it?

My teaching and research at the Ransom Center links with backstories from the Lyon archives that illuminate the kinds of youthful relationships that lay behind the decision to charge a newborn to institutional care—often after having run a rollercoaster of emotions as the couple started going out, promised to marry, and began as was usual to have sex before the official ceremony. Young pregnant women sometimes filed paternity suits in court if their partners resisted marrying them. These legal records are full of evocative details about the usual course of young people’s intimacy. As they had no effective technology to prevent pregnancy, sexually active women usually became pregnant quickly. If couples for a variety of reasons did not marry, family, employers, neighbors, clergy, and the local courts sought to hold young men responsible for the reproductive consequences of their sexual activity. If necessary they were held in prison until they agreed to pay the costs of the childbirth and take custody of the babies, leaving young women free to get back to work and re-set their lives. On occasion, the couple sought to resolve their untimely pregnancy in other ways—by attempting to induce an abortion or by engaging in neonatal infanticide (as autopsies on fetal remains found around the city showed). The couple might also decide to charge the baby to the foundling hospital, a strategy that allowed them to resume their lives. In the archives lie the answers to my students’ questions.

So how can we make sense of this pink ribbon, whose message reads “I’m going away but not leaving you”? Did the parents decide together to dispatch the baby with a ribbon that could symbolize their heartbreak, or did they mean it as a token the baby might have to keep later, or was it simply a distinctive identification marker? I wondered if there had been time to make a customized ribbon with such an apt message to tie on a baby’s wrist as a bracelet.

In the spring of 2019, almost ten years after I first saw the ribbon (and with it about to be on the cover of my book), I sat next to a colleague at a workshop in the UK about the histories of love and intimacy. After she talked about foundling tokens in her own research presentation, I showed her this photograph on my phone. She said, “What makes you think it’s a bracelet?” I was dumbfounded. What else could it be? She continued, “It looks like a garter to me.” Really? Sure enough, a quick search that evening took me down the rabbit holes of Pinterest (a very twenty-first century research mode) where I learned of a collection of very similar, albeit high-end French garters at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I also learned that this cheap, ephemeral female accessory is of a kind that rarely survives today because the belongings of working people were rarely saved. I had held a true archival treasure in my hand without ever realizing it.

My slow research—over 15 years and two continents in archives in France and libraries in the United States—involved unravelling layers of mysteries about the cataloging, the documents themselves, and occasionally a surviving artifact tucked in between sheets of paper.

—JULIE HARDWICK

A garter, of course, was perfect for my book about young couple’s intimacy. It was a type of cheap, fast-fashion item that became very popular in eighteenth-century Europe’s consumer revolution. In Lyon and the surrounding towns, many young men and women worked in the production of all kinds of textiles, from luxury silk to small affordable decorative items like these. The reverse shows very crude stitching secured the beadwork decoration to the ribbon in line with the rapid production of items. It still raises lots of questions. Did the baby’s mother buy it for herself? Did her boyfriend give it to her as a cheeky gift? Garters come in pairs, so what happened to the other one? Was it carefully chosen to send with the baby because of the emotional message, or was it dispatched with the baby because it was something very identifiable that was to hand and could be managed without?

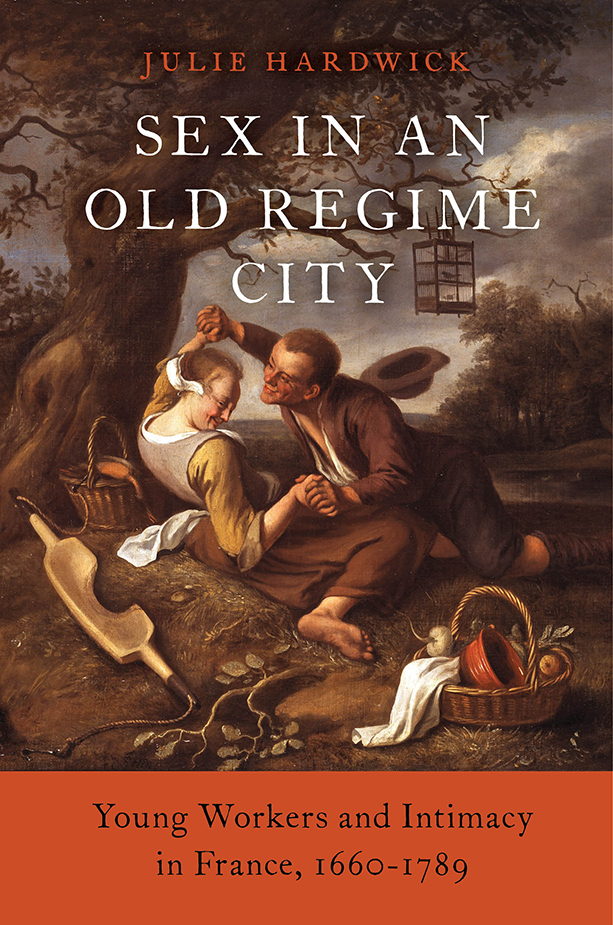

Despite the perfect fit between the garter and my book, the French text in the end made my editor chose another cover on the basis that most people could not read French. The cover painting perfectly epitomizes the ambiguities and complexities of young couple’s relationship in an immediately accessible way, but I still lament that it is not the cover that was my dreams. The garter story starts the book with a nice black-and-white photo. The editor did delight me, though, by tucking a tiny color photo of it inside the front cover flap, just as a garter was tucked away under a young woman’s clothes. And this particular—and provocative—one has been tucked for 250 years into a pile of papers as that stack travelled through a series of local archives.