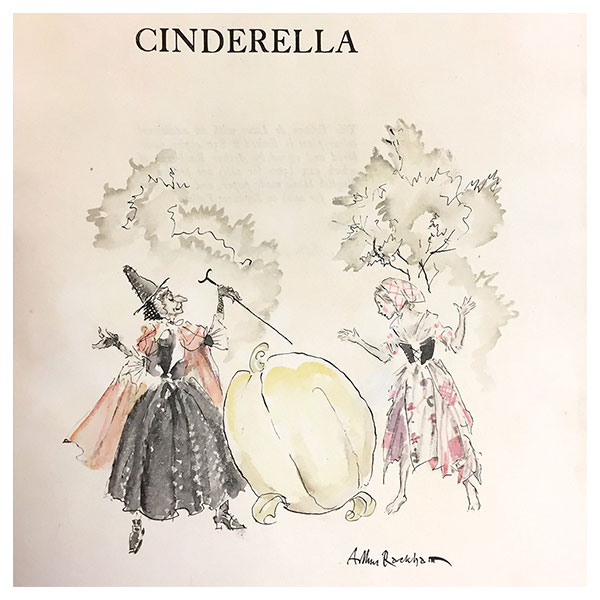

The turn of the twentieth century was the Golden Age of Illustration in the U.S. and the U.K., when, thanks to advances in print technology, a vigorous public appetite for finely illustrated books was met with works by illustrators such as Arthur Rackham (English, 1867-1939).

Edgar Allan Poe

Shakespeare scholar explores the Bard’s role in American culture

James Shapiro, Larry Miller Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, discusses Shakespeare in America at 7 p.m. this Thursday, May 1, at the Harry Ransom Center. A reception and book signing follow, and books will be available for sale. Shapiro’s newest work, Shakespeare in America: An… read more

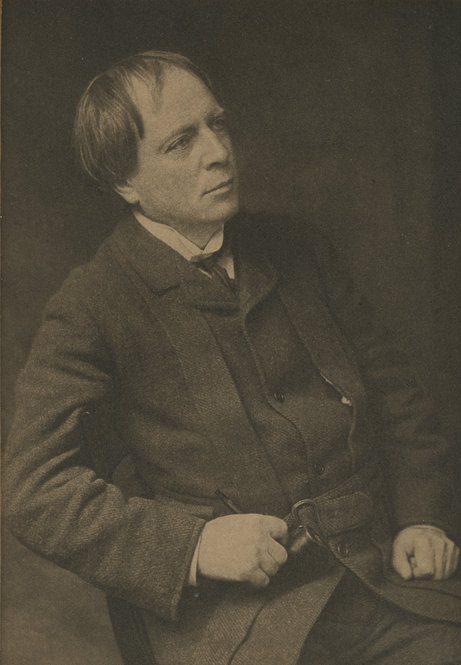

Arthur Machen, Welsh horror fiction author, turns 150 this week

The Welsh horror fiction author Arthur Machen turns 150 this week. Machen, an influential figure in the budding supernatural fiction scene of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, is best known for his novella “The Great God Pan,” and for accidentally proliferating a legend about angels protecting the British… read more