I. Artist: Venus and Adonis was painted by Filippo Lauri. Lauri lived from 1623-1694 in Italy, specifically in Rome. He was painting during the Baroque period, which is best described through opulence and grandeur. One thing that the art has in common during this Baroque period is that they involve drama. The drama can clearly be seen in Venus and Adonis because the work is meant to reflect the effects of love that can lead to despair. Lauri’s father was a Flemish landscape painter. Lauri studied painting under his father, then he studied under his brother, which led him to work for his brother-in-law. In 1654, Lauri became a member of the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Lauri had many other well-known paints of Greek myth like Apollo Flaying Marsyas, but Lauri also had paintings regarding Christian ideals.

I. Artist: Venus and Adonis was painted by Filippo Lauri. Lauri lived from 1623-1694 in Italy, specifically in Rome. He was painting during the Baroque period, which is best described through opulence and grandeur. One thing that the art has in common during this Baroque period is that they involve drama. The drama can clearly be seen in Venus and Adonis because the work is meant to reflect the effects of love that can lead to despair. Lauri’s father was a Flemish landscape painter. Lauri studied painting under his father, then he studied under his brother, which led him to work for his brother-in-law. In 1654, Lauri became a member of the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Lauri had many other well-known paints of Greek myth like Apollo Flaying Marsyas, but Lauri also had paintings regarding Christian ideals.

II. Date: There is not a definitive time that Venus and Adonis was created. However, it was believed to have been painted in 1671.

III. Location on Campus: Venus and Adonis can be found in the Blanton Museum. The painting can be specifically found in The Suida-Manning Collection. The Sudia-Manning Collection is a collection of Old Master paintings that was purchased by a family of art historians instead of people of grandeur like princes or merchants. The family would purchase pieces of art the same time that they would be studying the work. The collection contains 240 paintings and 390 drawings. The Sudia-Manning Collection has become one of the key collections for Old Master art because of the incredible size and pieces that have been accumulated through the Suida-Manning family. The collection was purchased and partially gifted to the University of Texas by Robert and Bertine Manning, Alessandra Manning Dolnier because they wanted to establish a legacy to pay homage to their parents and grandparents, while sharing this legacy to the rest of the world.

IV. Acquisition: Venus and Adonis was acquired by the Blanton Museum in 1999, making it the 361st piece to enter the collection. Venus and Adonis was placed on the UT campus for a plethora of reasons that help exemplify the overall themes of the entire museum. Firstly, the painting can fall into the theme of Time. Time within the Blanton Museum is meant to signify a flow time that the artist had to encapsulate within their work in innovative ways to carry on something of the past to current day viewers. Venus and Adonis exemplifies the theme of Time through Collapsing Time. The time within the painting has a distorted timeline, in that the painting does not just capture one moment within the story. Rather, the painting has aspects of multiple different scenes that may have occurred outside of the main event. For Venus and Adonis, this sense of collapsed time is highlighted there are many different scenes from the story portrayed in the painting like Adonis sitting under the myrtle tree (which is his mother, Myrrha, and this is described in the beginning of Book X of Metamorphoses), but Adonis is also is depicted with his spear, which will foreshadow his death by a boar in the end of the story. Plus, there are scenes in between those two events like Venus becoming infatuated with Adonis. It is clear to see that Lauri had used this painting to capture many parts of the myth from beginning to end. Therefore, there is a collapse of time because one scene cannot be explicitly described in the painting. Venus and Adonis also falls into the theme of The Art of Communication. This theme is meant to signify the different forms of expressing ideas through art whether it be in form of words or in form of painting. For Venus and Adonis, the painting falls under the subcategory of From Text to Image, which shows how artists have played with literature to give them inspiration for their pieces of work. The works of art can simply coincide with the original text or the art can also be opened to new interpretations of the artist and the viewer. Lauri’s work in Venus and Adonis follows along with Ovid’s telling of the story quite well. However, Lauri puts an emphasis on the Venus falling in love with Adonis to help build up the drama, which was a vital part of his work during the Baroque period. Lauri specifically adds Cupid striking Venus with an arrow. Although Cupid was alluded to as” the goddesses’ [Venus’] son” in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Cupid was not explicitly named. Therefore, the emphasis on Cupid within Lauri’s painting helps highlight the love that Venus is developing and the amount of infatuation that Venus has undergone. It is clear to see that Venus and Adonis exemplify some of the themes that can be seen throughout the Blanton Museum, thus making it the perfect piece to add to the collection.

V. Description: This painting is an oil painting on canvas. The size of the painting is 59 cm x 71.2 cm. The painting is framed in an intricately carved gold frame. The carvings on the frame have no known or distinct meaning, but it could be a sign of the opulence that Lauri was trying to exude during the Baroque period. The painting depicts Venus falling in love with Adonis, which can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book X. The two of them have a tragic love story in which Venus falls in love with Adonis. However, with every tragic love story the love must come to an end and that occurred when Adonis was killed by a boar while out hunting. Although in the painting, Adonis is not depicted being killed by a boar, there is foreshadowing of the event because Adonis is painted with a spear. Lauri follows the story of Venus and Adonis closely to what is depicted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. However, Lauri puts a major emphasis on the drama surrounding the troubled love surrounding Venus and Adonis.

Venus and Adonis is meant to symbolize that although Venus (Aphrodite) maybe the goddess of love, that does not mean Venus is immune to her own powers. Venus was overcome with lust and love from Cupid’s arrow and that caused her to act out of her regular actions. Eros does not have a positive effect on people, rather it makes a person act irrationally out of love. This can be seen through Venus because she is a goddess going after a mortal male. However, the repercussions of love are something to consider as well. Once Venus is aware of Adonis’ death, she begins to mourn and turns Adonis’ blood into the anemone flower. Through Venus’ actions, we can see how greatly affected she is by his death, which shows that Venus is suffering the consequences of loving someone deeply just like mortals would. Venus may be a goddess, but the emotions she faces are like the ones that mortals face as well. Venus is not immune to the effects of her power and can be hurt just as much, if not more than mortals by the effects of love.

Some of the clear classical mythological elements that are present in Venus and Adonis are the it shows the interaction between a divine being and a mortal and shows the origin of some life on earth (etiological myth), which is a metamorphosis. It also exemplifies the idea that gods and goddesses can experience outside forces like human emotions. Firstly, the interaction of a divine figure and a mortal is clearly seen through the interactions of Venus, a goddess, and Adonis, a mortal. A lot of the times, the interactions between the two involves an aspect of love or lust, whether it be the deity vying for the mortal or vice versa. In this story, Venus has fallen in love with Adonis at the hands of Cupid. Another classical element that can be seen is the etiological idea of a myth exemplifying an origin of a form of life. Although this idea is not directly painted on Venus and Adonis, the idea of the etiological myth is foreshadowed through Adonis’ spear. The explanation for a certain aspect of nature is best seen through the classic idea of metamorphosis within Venus and Adonis. Because Adonis went out hunting, Adonis ran into a boar that he attempted to stab it with his spear (which he is depicted with in the painting). However, Adonis fails and ends up dying. The blood of Adonis is used by Venus to create a red flower, anemone, in his honor. So, in theory, Adonis has metamorphosized into nature, specifically the anemone flower. Venus and Adonis’ story is able to give an explanation as to how the anemone flower has come to be today. Lastly, another classical mythological element that can be seen through Venus and Adonis is the idea that deities can feel the emotions of mortals, even though they may be seen in a higher status. Gods and goddesses are not immune to emotions, even if their sphere of activity may encompass the emotions that are overtaking them. This is clearly seen through Venus because in the painting she is clearly in love with Adonis. Her love is exemplified in they way that Venus also dresses. Venus had dressed up like Artemis, the goddess of hunting, to grasp Adonis’ attention because he is a hunter. Venus’ actions as an act of the yearning love that she had for Adonis. Love is Venus’ sphere of activity; however, Venus was clearly not immune to her own sphere. So, there is a contradictory nature of the gods. This almost humanizes the gods to be more understanding of the mortals. It allows mortals to relate to the gods in one instance to get a bigger message or lesson of a myth. Within Venus and Adonis, the bigger message could be the idea that love is not always fair. The person who is loving whole-heartedly is also the one who gets hurt the most by the love because they have become so attached to the other person

Personally, I believe Venus and Adonis shows the doubled-edged sword of love. Before Adonis and Venus’ love story could have been created, it had to stem from the love story of Myrrha for her father, Cinyras. Myrrha has been overcome with love for her father, but it is not the type of love that a child and parent share, rather Myrrha had developed an unnatural desire to have her father be her lover. Myrrha ends up tricking her father into sleeping with her, but her father finds out and attempts to kill her. However, Myrrha escapes only to discover that she is pregnant. So, she prays to be punished for her actions (Ovid, Metamorphoses, Myrrha Transformed to a Tree). Myrrha is turned into a tree that Adonis is depicted sitting under in the painting. The double-edge sword of love is seen through Myrrha and Cinyras in that love can be so blinding that we would act out of character. This is seen through Myrrha. Myrrha is so blinded by the love that she has for her father that she is unable to think about the repercussions of her actions. Love has made her unwise and made her act out against the social norms to pursue an incest relationship. From an outsider’s point of view, it was clear to see that Myrrha’s actions were unthinkable to most people. However, once the audience can see the completely spell of love that Myrrha was under there is more understanding of why lines may have been blurred to Myrrha. Cinyras and Myrrha’s relations led to the creation of Adonis, their son. Adonis then becomes subject to the love of Venus. Adonis catches the eye of Venus and she becomes interested in Adonis. However, Venus’ attraction to Adonis is heighten by Cupid’s arrow, which is depicted in the painting. Venus had given Adonis advice to “keep away from all such savage animals,” which served as a warning for Adonis’ safety (Ovid, Metamorphoses, Adonis Transformed). However, Adonis does not listen to the advice and goes after a wild boar with his spear, which is foreshadowed in the painting. This leads to the death of Adonis, leaving Venus with immense grief over Adonis’ death. Love playing a double-edged sword in this instance is clearly seen through Venus. For one, Venus is the goddess of love, but is unable to control her own realm of activity as she is struck with love over Adonis. So, Venus is able to relate in Myrrha in a sense that both were acting out of their typical character under the spell of love. However, the bigger idea of love being a double-edged sword is the potential effects that are felt with love. For Venus, her love for Adonis could be seen as a happy, lustful time for Venus. There was a sense of a caring love too because Venus attempts to warn Adonis against harmful activities. Those who love the most will also be hurt the most. Adonis’ death serves to symbolize the idea of the magnitude of Venus’ love. Love may bring lust upon a person; however, when the lust is gone, reality sets in and that can cause a grief that is unimaginable by many. Therefore, Venus and Adonis is attempting to exaggerate the love that Venus has for Adonis to help further exaggerate the pain that Venus will later feel after Adonis’ death.

Bibliography

“Collapsing Time.” Blanton Museum of Art. June 15, 2017. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://blantonmuseum.org/chapter/collapsing-time/.

“Filippo Lauri.” Wikipedia. January 19, 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filippo_Lauri.

“From Text to Image.” Blanton Museum of Art. June 15, 2017. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://blantonmuseum.org/chapter/from-text-to-image/.

Lou, Mary, and Shovova. “Exploring the Extravagance and Drama of Baroque Art and Architecture.” My Modern Met. March 23, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://mymodernmet.com/baroque- period/.

“OVID, METAMORPHOSES 10.” OVID, METAMORPHOSES 10 – Theoi Classical Texts Library. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidMetamorphoses10.html#9.

“Suida-Manning Collection at the Blanton Museum.” The Magazine Antiques. January 26, 2017. Accessed April 24, 2019. http://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/old-masters-at-the-blanton/.

“Venus and Adonis · Blanton Museum of Art Collections.” Omeka RSS. Accessed April 24, 2019. http://utw10658.utweb.utexas.edu/items/show/2840.

By Emma Tran

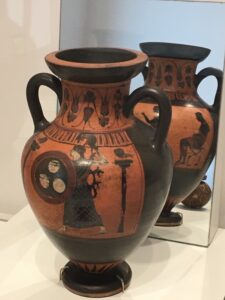

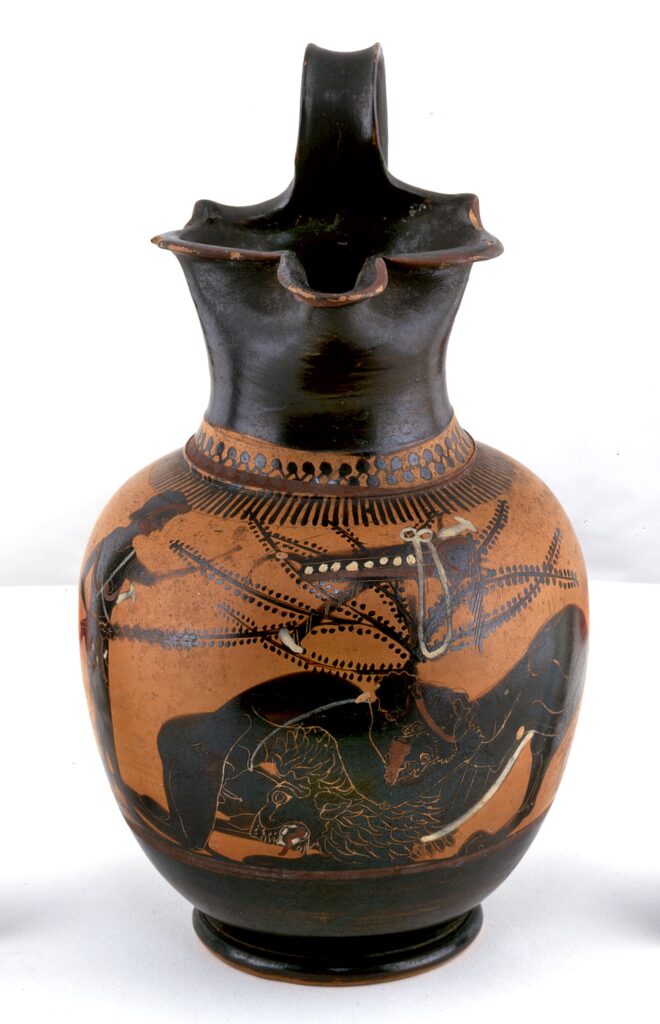

I. This artifact is described as a Black-Figured Neck-Amphora of Panathenaic Shape, otherwise known as an oil container. The painter of the amphora is unknown (Blanton Museum).[1] II. The amphora was created around 540 BCE (6th century BCE) and founded in Athens.

I. This artifact is described as a Black-Figured Neck-Amphora of Panathenaic Shape, otherwise known as an oil container. The painter of the amphora is unknown (Blanton Museum).[1] II. The amphora was created around 540 BCE (6th century BCE) and founded in Athens.

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called

Although Greek drama, particularly tragedies, were often set in the heroic world of Greek myth, they were used as a way of investigating contemporary Greek issues. Many of the narratives of Greek myth that are preserved in the writings of mythographers are based on the dramatic tellings of Greek myths by Athenian tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. In Greek myth, the dramatic arts of poetry, music, and dance were said to be inspired by female deities called  Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

Greek comedies generally had far less to do with myth than the genres of Greek tragedy and satyr. The early Greek comedies were mainly satirical, mocking political figures and people of importance for their vanity and foolishness. Our primary example of comedy is from the playwright Aristophanes. One the few examples of Greek comedies with an extended treatment of characters in Greek myth is Aristophanes’ Frogs. Frogs tells the story of how the god Dionysus travels to the underworld to bring the tragedian Euripides back from the dead because of the poor quality of Athens’ living tragedians. The potential for irreverent depictions of the gods can be observed in the character of the god Dionysus, whose behavior and numerous errors along the way to the home of Hades provide the primary source of humor in this comedy.

I. Artist: The creator (sculptor) of the statue of Hera of Samos is unknown – the Blanton museum lists the creator as “Anonymous”. The inscription on the dress of the statue reads “Cheramyes dedicated me, a statue of Hera.” This implies that Cheramyes, an Greek aristocrat from Ionia, was the one who commissioned this piece as a monument to the

I. Artist: The creator (sculptor) of the statue of Hera of Samos is unknown – the Blanton museum lists the creator as “Anonymous”. The inscription on the dress of the statue reads “Cheramyes dedicated me, a statue of Hera.” This implies that Cheramyes, an Greek aristocrat from Ionia, was the one who commissioned this piece as a monument to the I. Architect: The Union building at the University of Texas was designed and completed by Robert L. White and Paul Cret. Paul Cret was an architect from Lyon, France that dedicated his work to design many famous public buildings across the United States. In nineteen thirty, Paul Crete was hired by the University of Texas as a consulting architect for a construction plan at the University, including the construction of the Union building, and continued to work at the University until his death fifteen years later. Some of his most notable works at the University of Texas include the Library on campus, the Architecture building, the Union building, the Home Economics building, the Littlefield memorial, the Yount House, the Texas Memorial Museum, and many dormitories on campus. Comparatively, Robert L. White was an architect from in Cooper, Texas. In nineteen twenty-one, White finished his bachelor’s degree in architecture at the University of Texas, and then came back to the University of Texas nine years later to obtain his master’s degree in architecture. While White was at the University of Texas attending graduate school for architecture, he became the supervising architect at the University of Texas. During this time, White was able to plan and execute many of the large building projects at the University of Texas during that were completed during the nineteen thirties, until his resignation twenty-eight years later. Some of his most famous constructions on campus include the Main Building, Goldsmith Hall, the Texas Union, and the Hogg Auditorium. Both Paul Crete and Robert L. White were important figures in the construction of the Union building and in the construction of many other important buildings on campus at the University of Texas.

I. Architect: The Union building at the University of Texas was designed and completed by Robert L. White and Paul Cret. Paul Cret was an architect from Lyon, France that dedicated his work to design many famous public buildings across the United States. In nineteen thirty, Paul Crete was hired by the University of Texas as a consulting architect for a construction plan at the University, including the construction of the Union building, and continued to work at the University until his death fifteen years later. Some of his most notable works at the University of Texas include the Library on campus, the Architecture building, the Union building, the Home Economics building, the Littlefield memorial, the Yount House, the Texas Memorial Museum, and many dormitories on campus. Comparatively, Robert L. White was an architect from in Cooper, Texas. In nineteen twenty-one, White finished his bachelor’s degree in architecture at the University of Texas, and then came back to the University of Texas nine years later to obtain his master’s degree in architecture. While White was at the University of Texas attending graduate school for architecture, he became the supervising architect at the University of Texas. During this time, White was able to plan and execute many of the large building projects at the University of Texas during that were completed during the nineteen thirties, until his resignation twenty-eight years later. Some of his most famous constructions on campus include the Main Building, Goldsmith Hall, the Texas Union, and the Hogg Auditorium. Both Paul Crete and Robert L. White were important figures in the construction of the Union building and in the construction of many other important buildings on campus at the University of Texas. I. Artist: Venus and Adonis was painted by Filippo Lauri. Lauri lived from 1623-1694 in Italy, specifically in Rome. He was painting during the Baroque period, which is best described through opulence and grandeur. One thing that the art has in common during this Baroque period is that they involve drama. The drama can clearly be seen in Venus and Adonis because the work is meant to reflect the effects of love that can lead to despair. Lauri’s father was a Flemish landscape painter. Lauri studied painting under his father, then he studied under his brother, which led him to work for his brother-in-law. In 1654, Lauri became a member of the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Lauri had many other well-known paints of Greek myth like Apollo Flaying Marsyas, but Lauri also had paintings regarding Christian ideals.

I. Artist: Venus and Adonis was painted by Filippo Lauri. Lauri lived from 1623-1694 in Italy, specifically in Rome. He was painting during the Baroque period, which is best described through opulence and grandeur. One thing that the art has in common during this Baroque period is that they involve drama. The drama can clearly be seen in Venus and Adonis because the work is meant to reflect the effects of love that can lead to despair. Lauri’s father was a Flemish landscape painter. Lauri studied painting under his father, then he studied under his brother, which led him to work for his brother-in-law. In 1654, Lauri became a member of the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Lauri had many other well-known paints of Greek myth like Apollo Flaying Marsyas, but Lauri also had paintings regarding Christian ideals. I. Architect: The creation of this artwork is accredited to Paul Cret, who was the consulting architect responsible for the University of Texas Campus Master Plan and the design of the tower (Berry). Paul Cret was a French born architect who headed the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania when he was hired to design the main building of the University of Texas campus (Nicar). Cret incorporated many aspects of Greek myth that held symbolic meaning for the university, including the head of Athena in order to accomplish his goal of making the building a meaningful and significant landmark at the University of Texas (Nicar).

I. Architect: The creation of this artwork is accredited to Paul Cret, who was the consulting architect responsible for the University of Texas Campus Master Plan and the design of the tower (Berry). Paul Cret was a French born architect who headed the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania when he was hired to design the main building of the University of Texas campus (Nicar). Cret incorporated many aspects of Greek myth that held symbolic meaning for the university, including the head of Athena in order to accomplish his goal of making the building a meaningful and significant landmark at the University of Texas (Nicar). I. Architect: The statuettes on Sutton Hall were created by the architect Cass Gilbert. He was the campus architect for the University of Texas from 1909-1922 and also built Battle Hall and the Woolworth building. He was heavily inspired by the Mediterranean Renaissance style and built both Battle and Sutton Hall in reflection of it.

I. Architect: The statuettes on Sutton Hall were created by the architect Cass Gilbert. He was the campus architect for the University of Texas from 1909-1922 and also built Battle Hall and the Woolworth building. He was heavily inspired by the Mediterranean Renaissance style and built both Battle and Sutton Hall in reflection of it.

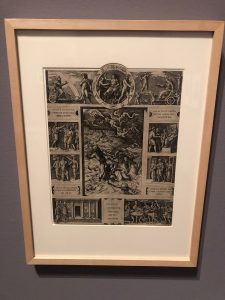

I. Artist: The author of Quos Ego was Marcantonio Raimondi. Marcantonio was an engraver who was born close to Bologna, Italy in 1480 (Britannica 2019). He was highly skilled in his area of work, and this could possibly be credited to the person who trained him, Francia, who was a successful goldsmith as well as an extraordinary painter (Britannica 2019). Most of Raimondi’s best work was created when he started copying the works of Michaelangelo and Raphael (Britannica 2019). He was even fortunate enough to meet Raphael himself, who seemed to like Raimondi enough to insert him into his Explusion of Heliodorus (1513) (Britannica 2019). Raimondi’s connection to Raphael was his most important aspect when it came to his artwork. Some of Raimondi’s printings were Dream of Raphael (1507), The Climbers (1510), Massacre of the Innocents (1512-1513), and The Judgement of Paris (1510 – 1520). While many of Marcantonio Raimondi’s engravings were recreations, there was no doubt that the man was a wonderful artist.

I. Artist: The author of Quos Ego was Marcantonio Raimondi. Marcantonio was an engraver who was born close to Bologna, Italy in 1480 (Britannica 2019). He was highly skilled in his area of work, and this could possibly be credited to the person who trained him, Francia, who was a successful goldsmith as well as an extraordinary painter (Britannica 2019). Most of Raimondi’s best work was created when he started copying the works of Michaelangelo and Raphael (Britannica 2019). He was even fortunate enough to meet Raphael himself, who seemed to like Raimondi enough to insert him into his Explusion of Heliodorus (1513) (Britannica 2019). Raimondi’s connection to Raphael was his most important aspect when it came to his artwork. Some of Raimondi’s printings were Dream of Raphael (1507), The Climbers (1510), Massacre of the Innocents (1512-1513), and The Judgement of Paris (1510 – 1520). While many of Marcantonio Raimondi’s engravings were recreations, there was no doubt that the man was a wonderful artist.