By Raymond-Jean Frontain

What brings people to the theater, a speaker explains in “Hidden Agendas”—a sketch that Terrence McNally wrote in the early 1990s in response to a censorship crisis at the National Endowment for the Arts—is “the expectation that the miracle of communication will take place. […] Words, sounds, gestures, feelings, thoughts! The things that connect us and make us human. The hope for that connection!”

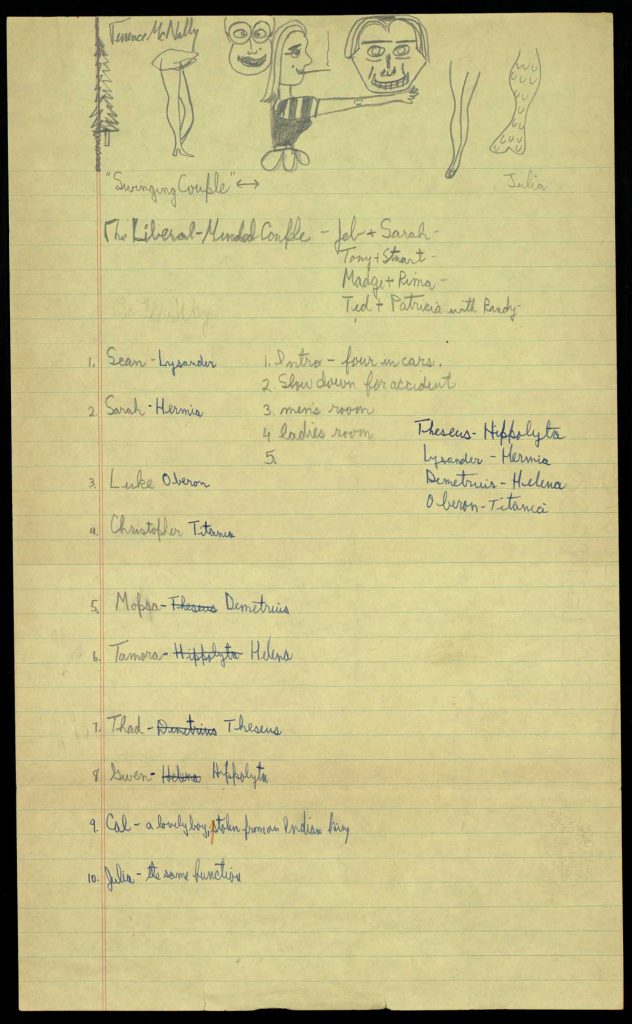

The Ransom Center’s McNally archive bears witness to the playwright’s extraordinary ability to establish connections. It contains, for example, the manuscript of McNally’s first play, written in ink on notebook paper in an adolescent hand, which dramatizes how composer George Gershwin met, fell in love with, and married the woman who would become his great collaborator, “Ira.” (Apparently, in his fantasies of New York’s sophisticated set, it never occurred to the Corpus Christi, Texas, teenager that Ira Gershwin was the composer’s brother, not his wife.)

But this first creative effort, with its emphasis upon the experience of theatrical collaboration, proved prophetic for McNally and may be accounted the single greatest theatrical collaborator of his generation, working with John Kander and Fred Ebb on the musicals The Rink, Kiss of the Spider Woman, and The Visit; with Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens on Ragtime and A Man of No Importance; with David Yazbeck on The Full Monty; and with Jake Heggie on the opera, Dead Man Walking.

In addition, he has collaborated with fellow playwrights Israel Horovitz and Leonard Melfi on productions in which—in an arrangement similar to that practiced by the fifteenth-century Japanese renga no haikai poets—each was challenged to compose a one-act play on a word or phrase in a three-part title (Morning, Noon and Night; “Cigarettes, Whiskey, and Wild, Wild Women”; Faith, Hope and Charity), the only limitation being previously agreed-upon setting and number of characters.

The archive bears witness as well to McNally’s ability to connect with, and inspire loyalty among, his fellow professionals. The collection contains two letters from novelist John Steinbeck, whose teenage sons McNally had tutored when he was just out of college, and for whose East of Eden McNally would write the 1968 musical version. Present in 1965 at the premiere of the 26-year-old McNally’s first commercially produced play, And Things That Go Bump in the Night, Steinbeck was dismayed to see an intelligent, thought-provoking play blasted by critics who resented its bringing to Broadway the dark absurdism and subversive sexuality that had previously been consigned to Off Broadway. “Remember the old Texas saying,” Steinbeck comforted his young friend, “‘Who ain’t been thro’ed, ain’t rode.’ It’s a kind of welcome into professional circles.”

McNally would enjoy a more extraordinary outpouring of support nearly 35 years later when religious fundamentalists, provoked by grossly misinformed articles in the New York Post, mounted a virulent campaign to forestall the production of his Corpus Christi. A public defense of the play was mounted by fellow playwrights Athol Fugard and Craig Lucas, while outside the theater each evening, counter demonstrations were organized by television producer Norman Lear’s People for the American Way. The Ransom Center’s archive contains McNally’s letter to his besieged cast on closing night, as well as a copy of a lengthy letter written a year after the controversy in which McNally ruminates upon the problems of censorship in contemporary theater. Significantly, the Center’s collection also includes the first draft, first rehearsal script, and subsequent revised scripts, from which can be documented the gross inaccuracy of the fundamentalists’ accusations.

Finally, the archive documents how powerfully theater-goers connect with McNally’s plays, for the collection contains not only letters from actors attesting to the personal transformations that they experienced while playing one of his parts, but from strangers who felt compelled to tell him how deeply moved they were by his reiterated theme of the difficulties of, and urgent need for, human connection. Among the most moving may be those from mothers of AIDS sufferers sent following the televised production of Andre’s Mother, the writers signing themselves simply “Peter’s Mother” or “Richard’s Mother.”

The Center’s archive offers a portrait of American theater as it was reinventing itself in the Off Broadway movement of the 1960s, through the emergence of strong regional theaters in Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Diego, and through the changing fortunes of the world that McNally skewers in Broadway, Broadway. It contains, for example, not only the playwright’s own weekly columns in the 1970s for a now-defunct New York alternative newspaper in which he commented on the state of the theater in a series of open letters to influential personalities like musical star Ethel Merman and critic Walter Kerr, but letters from fellow playwrights like Neil Simon (who commiserates with McNally about the annoying sounds made by the “crickets”—that is, critics) and Robert Anderson (who speculates that Love! Valour! Compassion! was not awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the same reason that his own Tea and Sympathy was passed over in 1953: its treatment of homosexuality).

And it bears witness to McNally’s engagement with actors like James Coco, for whom he wrote major parts in several plays even while comically dissecting their relationship in It’s Only a Play, and Angela Lansbury, whose letters to McNally analyzing the character of Clair Zachnassian in The Visit (a part written originally for her) may be among the most intelligent in actors literature, and a unique record of the creative collaboration between actor and playwright.

Even the opening night congratulatory notes that McNally received from friends and colleagues illuminate the networks that are at the heart of modern American drama: a letter from actress Uta Hagen written following the premiere of Master Class in 1995 recalls a walk she’d taken with McNally more than 30 years earlier on the beach at Edward Albee’s Montauk estate, which she speculates was the genesis of Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Seascape.

“We gotta connect. We just have to. Or we die,” Johnny struggles to convince an emotionally scarred Frankie in McNally’s Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. The Center’s McNally archive documents the connections nurtured by McNally that allow American theater to thrive.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas and the editor of ANQ: American Notes and Queries. His work in the McNally archive was supported by a Mellon-South Central Modern Language Association fellowship.

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2009 issue of Ransom Edition.

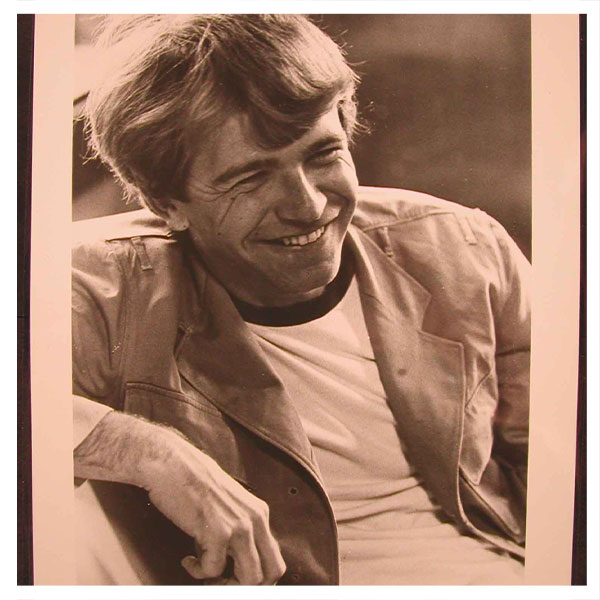

Top image: Terrence McNally photo by unidentified photographer.