If under some truly unfortunate circumstances you found yourself imprisoned on a penal colony thousands of miles from home and infamous worldwide for its unlivable conditions, a talent for writing might be your best bet for survival. A considerable amount of perseverance and good luck would also come in handy.

Such was the case of René Belbenoit, a native Parisian who, after returning from the front lines of World War I as a teenager, was sentenced in 1921 to eight years of hard labor in French Guiana for a series of thefts. He first arrived at the penal colony in Saint-Laurent du Maroni in 1923 at the age of 24, and after 14 years of misery, punctuated by several hapless escape attempts, an emaciated and toothless Belbenoit snuck his way into Los Angeles.

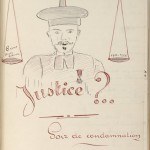

Short in stature, slight of build, and cheerful by nature, Belbenoit felt isolated among his fellow inmates, many of whom had committed far more violent crimes than his own. But his classification by the administration as “incorrigible,” a distinction that landed him in solitary confinement on the particularly hostile Devil’s Island, was in one sense entirely fitting: no matter what punishment he faced, Belbenoit continued to make escape attempts until he’d secured his freedom. His final count totaled four prison breaks and two illegal escapes as a libéré, a “freed” ex-convict who, despite having finished his sentence, is forbidden to leave Guiana.

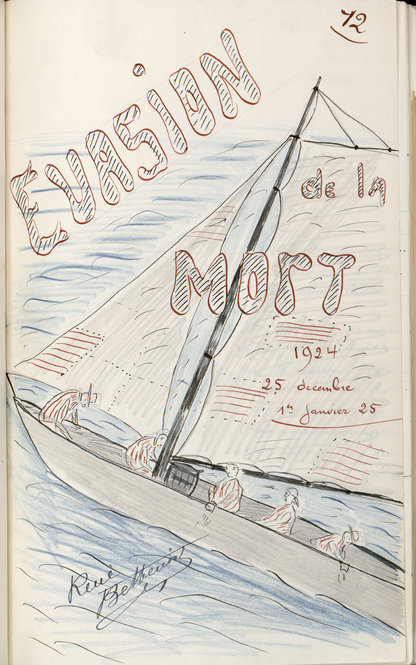

Belbenoit wrote about the experience in his memoir Dry Guillotine, which takes its title from the disdainful nickname the prisoners gave to their penal home. The Ransom Center’s René Belbenoit collection contains the book’s manuscript, a 900-page tome including illustrations, an official prisoner booklet, and several flattened cigarette packets with notes written on the back, presumably from the time Belbenoit spent in prison. He began keeping a written record of his time in Guiana in 1926, but many of his early notes were destroyed by prison guards. When possible, he solicited help from the mother superior of a local nunnery to safeguard his writings. He brought them along on every escape attempt, wrapping them in oilskins for protection from the elements, but many were ruined en route. When something was lost, he would simply rewrite it.

Detailed recollections of prison misery constitute much of the first half of the memoir. The backbreaking labor, often performed naked and shoeless, was a traumatic shock for Belbenoit, as were the swarming mosquitoes and sweltering heat of the tropics. The prison administration took no pains to preserve the inmates’ health, as ships full of replacements arrived regularly. According to Belbenoit, of the average 700 annual arrivals in Guiana, approximately 400 would die in their first year. He writes, “The policy of the Administration is to kill, not to better or reclaim.”

In addition to his accounts of the prisoners’ suffering and the guards’ brutality, Belbenoit offers unique insight into the social structure of the all-male group of the condemned. Complex hierarchies emerged as the older, more aggressive inmates battled each other to win younger boys as their môme, or submissive sexual partners. Subterfuge became a requisite skill for survival in French Guiana. Bribery was ubiquitous but risky, as the possession of money was strictly forbidden. The most experienced prisoners were also adept malingerers, often smoking quinine to sham fever for a day of rest in the infirmary.

Belbenoit, a charming storyteller and known exaggerator, wields compelling narrative at the expense of incomplete veracity. But even his likely embellished accounts, the most dramatic of which would find a comfortable home in soap opera subplots, are revealing. Foremost among these are the tales of Belbenoit’s affair with a 16-year-old daughter of an administrator, and that of a complicated love triangle involving a prisoner, his môme, and a guard’s wife. Fourteen years of enduring both physical torture and torturous monotony honed Belbenoit’s ability to captivate an audience, winning him a network of friends that was essential to his survival.

So while the inmates’ complaints about their merciless treatment fell on deaf ears in Guiana, Belbenoit found an eager readership in the developed world, where headlines announced the departure of penal ships in heavy terms: “Broken Men Sail for Devil’s Island” and “Condemned to a Living Death.” Selling off his notes to visiting reporters turned out to be his most lucrative enterprise, which in turn afforded him a number of unlikely prospects for escape. Blair Niles, a travel writer and novelist, encountered Belbenoit in 1926. She visited with him for several days, buying the notes he had dutifully collected and preserved for 100 francs. Belbenoit used the money to stage an unsuccessful escape, which resulted in extreme, nearly fatal punishment. Niles returned to the United States, publishing her bestselling biography of Belbenoit in 1928, titled Condemned to Devil’s Island. The book, which was adapted into the 1929 film Condemned, was influential in international prison reform movements.

But Belbenoit never succumbed to the discouragement of his previous failures, and in 1935, a similar opportunity ultimately led to his freedom. An American filmmaker, whom Belbenoit leaves unnamed in his memoir, apparently offered 200 dollars in exchange for intimate knowledge of how one would conduct a dramatic escape in the tropics. Despite Belbenoit’s answer that the only feasible strategy would be to leave by the sea, the filmmaker retorted, “This must be an escape through the jungles… combat with fierce animals, snakes, swamps… It makes a better picture.” Perhaps it was from this man that Belbenoit learned the fungible value of an exciting story.

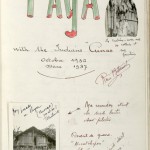

Using the cash to secure a 19-foot boat and some provisions, Belbenoit escaped by sea with five other convicts. They were well-received by the British authorities in Trinidad, “true sportsmen” who opted not to have them deported. Belbenoit separated from the group and made his way to Central America, where he spent seven months capturing butterflies to sell and living with native tribes on his journey northward.

Belbenoit finally reached El Salvador, stowed away on a ship, and arrived in Los Angeles in 1937. He made his way to New York, where he published Dry Guillotine in 1938, by which time France had stopped sending prisoners to the penal colony. The prison at Devil’s Island was officially closed eight years later.

Though now largely forgotten, Belbenoit’s extraordinary experience captured media attention for the remainder of his life. He appeared on the television series This Is Your Life and in several articles in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times, and he worked briefly at Warner Bros. as a technical advisor for the 1944 film Passage to Marseille. Belbenoit made the most of his compelling story, understanding just how much power it could wield. After all, it had saved his life.

Additional archival materials for Belbenoit are located in the E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc. Records at Syracuse University, in the Warner Brothers Archive at the University of Southern California, and in the Ralph Edwards Productions Production Records at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Click on thumbnails below to view larger images.