Acclaimed novelist, poet, and essayist Julia Alvarez speaks about her life and work with University of Texas at Austin professor Jennifer M. Wilks in a Harry Ransom Lecture this Monday, March 31 at 7 p.m. in Jessen Auditorium at Homer Rainey Hall. A book signing and reception follow at the Ransom Center. This lecture is presented by the University Co-op and co-sponsored by the 2013–2014 Texas Institute for Literary and Textual Studies (TILTS) Symposia: Reading Race in Literature and Film. Alvarez’s archive resides at the Ransom Center.

In an interview with Cultural Compass, Alvarez shares her thoughts on women in the literary canon, cultural identity, and more.

Stories about men are considered universal, but stories about women are often considered “women’s fiction.” What do you think can be done to change this trend? How have your books centering on female protagonists been received with regard to this?

We’ve made a lot of progress. In my own lifetime as a writer, now over 40 years, I’ve seen a sea change in interest in authors of ethnic/racial/gender diversity—both as a writer in what gets published but also as a writer in the academy in the curriculum, the books departments select for their core readings.

That said, we are still living in the shadow of that old canonical/gated understanding of what constitutes classic, serious fiction. The travails and writing by men, mostly white, with some exceptions. Women’s novels are often considered lite fair. (Is there a male version of chicklit denomination?) What was Samuel Johnson’s comment about women preachers? “A woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.” Well in many quarters, this was also the attitude toward women’s writing.

So, even though many of the most admired and serious American novelists and poets now come from other traditions, ethnicities, races, and many of them are female, that old mentality is there, like a gas we breathe and don’t even know it. Still it was daunting to read the op-ed in New York Times Book Review, two years ago, by Meg Wolitzer, “The Second Shelf: On the Rules of Literacy Fiction for Men and Women.”

Additionally, it’s not just that women’s fiction isn’t taken as seriously, [or] reviewed as often, but also the default characters and plots of serious fiction are still those of the mainstream culture. So often when I write about a Dominican American family, it’s assumed this has to be my story. Why? Because otherwise I’d write about a John Cheever family in Connecticut? (I love John Cheever’s fiction, but those aren’t the stories I have to tell.) It’s as if our characters are only allowed limited minority fiction status—often there are courses just in this area, an infusion of fairness into an otherwise distorted canon! It’s a curious and often unconscious set of assumptions and expectations about who gets to have their stories told. Of course, I know this, too, is changing, but as Wolitzer cautions us, we ain’t there yet.

If I may take it a step further into personal experience: when I wrote In the Time of the Butterflies (1994) I told the story of the dictatorship seen for the first time from a female point of view. I heard from my friend, Dominican historian and author Bernardo Vega that he introduced Mario Vargas Llosa to the novel, and MVL got very interested in the dictatorship and subsequent “democratic dictatorship” by Balaguer. His novel, La Fiesta del Chivo (The Feast of the Goat) (2000), is often cited as the seminal work of fiction about those years. I admire the novel, and none of this is MVL’s “fault.” Just the way critics and even readers have these unexamined assumptions. Good for you for bringing up the question and forcing us to see these assumptions are still out there.

What can be done to change trend? My response is to keep writing. Spike Lee once said the only way to be avoid being flash-proof is to keep doing your work.

Attitudes/assumptions change slowly, over time, probably not during my watch, but if I don’t do my part, change won’t happen at all.

Many people categorize you as a Latina, Dominican, or bicultural writer. How would you like to be perceived as a writer?

I like the quote, attributed to Terence, the Roman playwright, “I am a human being, nothing human is alien to me.” That could well be the motto of literature. It’s how I would ultimately want to be remembered: one of the storytellers from my specific “tribe,” but telling the stories to all of us. We are all feeding the same sea, as Jean Rhys put it, as we come down and flow into it from our different mountains and landscapes.

After all, one of the things literature teaches—and why I gave myself to this “calling”—was that I recognized that this was the one place where the table was set for all. All the wonderful stories, poems are our legacy as part of the human family—our communal treasure chest, but in order to access it, of course, you need to get the key, that is, education, learning to read, having the time and opportunity to claim your legacy.

For so many years, I felt denied entry into that world of serious American literature (as Langston Hughes noted in his wonderful little poem, “I, too, Sing America”) so that when I finally was published I claimed my LATINA voice, my traditions, my culture with a vengeance. Often it was because I sensed that I needed to make a space and place for other kinds of stories on the shelf of American fiction. But as I get older, what’s important to me is that these terms describe the sources of my stories, my history, my traditions, but that they shouldn’t be used to limit my subjects, or limit my readership to only those in the tight circle of my own culture or background. Again stories are about the big circle, the gathering of the different tribes of the human family. Getting down into ethnic/racial bunkers of literature totally negates what they are about.

Which of your works means the most to you, and why? Which one was most difficult to write? The most fun?

Oh dear, that’s like asking a mother to pick a favorite child! Each work has taught me things I needed to learn—about technique/writing, about history/characters/situations I was curious to understand. So, each one was meaningful to me at the time.

I suppose writing the Tía Lola books for young readers was the most fun, just because Tía Lola is such a sassy, fun-loving tía. I’d catch myself eager to start the writing day, wondering what trouble she’d get into, and as the author, how I’d get her out of the fix she was in, or had gotten me into.

That said, on a good writing day, any book I am laboring on is “fun,” and even those fun books are difficult to write if I want to get them right. Let’s face it, good writing is hard work. I have this one quote about revision/writing by James Dickey that I like to share with my students:

“It takes an awful lot of time for me to write anything. I have endless drafts, one after another; and I try out 50, 75, or a hundred variations to a single line of poetry sometimes. I work on the process of refining low-grade ore. I get maybe a couple of nuggets of gold out of 50 tons of dirt. It is tough for me. No, I am not inspired.”

I guess I wouldn’t go that far—of saying I’m never inspired. But at the end of the day, the inspired piece of writing and the one that took 50 tons of dirt to get to a single nugget of golden writing—they have to be indistinguishable from each other.

Most meaningful? Always the writing I’m currently working on because that’s the cutting edge, the material or technique or character that I’m trying to understand, to serve, to get down on paper.

A little rambling, I know, but as the quote ascribed both to Twain and to Pascal (the problem with Internet searches!): “I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.”

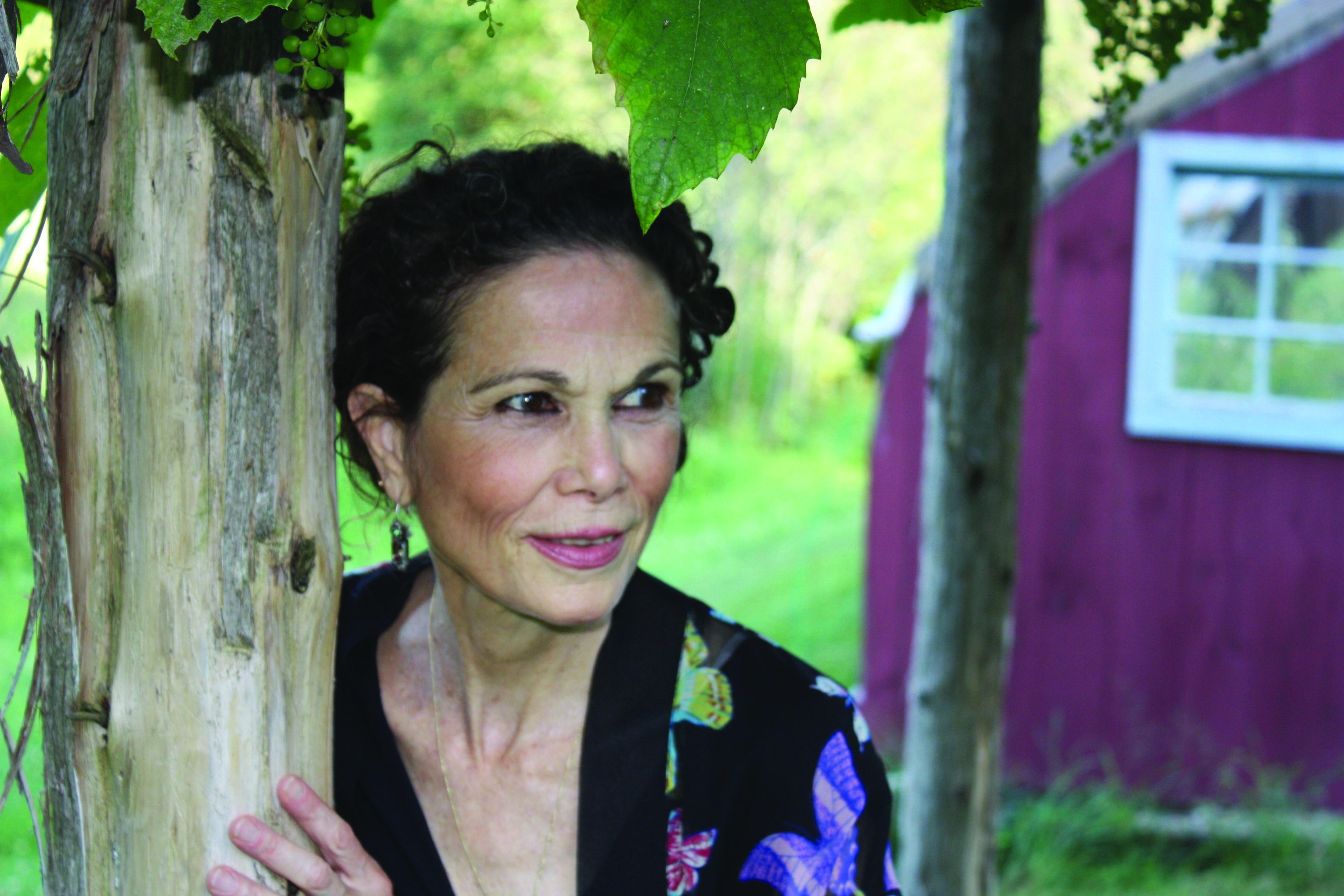

Image: Photo of Julia Alvarez by Bill Eichner.