by JEFFREY W. BARBEAU

This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

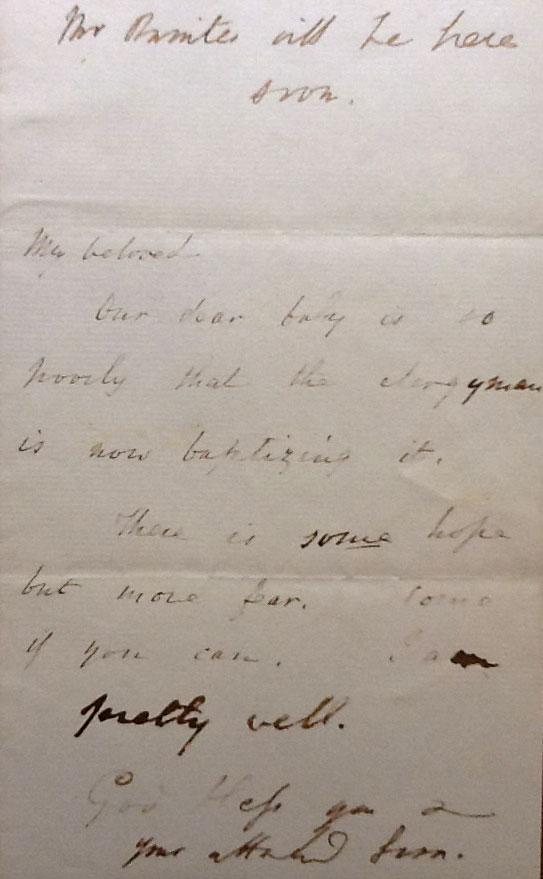

Sometimes the scrawled letters on a page slow reading to a halt. Unlike printed words in a bound volume or transcripts that risk sanitizing history, handwriting produces an entirely different reading experience. Words unfold, as they were written originally, and events take on new meaning in the materiality of the archives. The manuscript of a letter or diary may be neat and legible when composed in tranquility, or scribbled hastily in times of anger or mourning. In print, the end of Sara Coleridge’s life was hardly a mystery, but reading her manuscripts changed everything for me.

My first encounter with Sara Coleridge came by way of her father, the poet and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His name is synonymous with the British Romantic movement. An enigmatic figure, Sara’s father is read by children in classrooms around the world. Students hear the words of an ancient mariner, entranced by his heinous crimes. They listen to his spectacular, poetic vision in “Kubla Khan” and encounter a man caught up in the wonder of imagination and the supernatural.

Others associate the name “Coleridge” with nature. Along with his friend William Wordsworth, Coleridge wrote of nature’s “secret ministry,” concluding with hopeful promises for his son Hartley in “Frost at Midnight”:

… so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.[1]

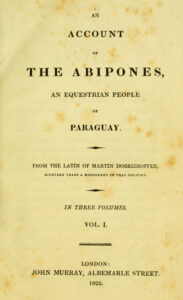

Sara was far more like the best of her father than anyone realized. Like him, she was sickly and lost. He wasn’t even present for her birth—or most of her youth. He too had lost a father while yet a boy. And while much attention was paid to her elder brothers, Sara learned in the library of her guardian father, Robert Southey, translating works written in Portuguese in her spare time—a “suitable” occupation for the girl, while others pressed on eagerly in public pursuits.

For a long time, Sara Coleridge had remained something of a mystery to me. I knew she edited her father’s works after his death, wrote some familiar lines of poetry (“The Months” with its memorable rhymes beginning “January brings the snow”), and even had an interest in her father’s later philosophical theology. Yet, among my many colleagues in the field, few could tell me much about these later writings. Sara’s memory, it seemed, was lost.

Even naming Sara Coleridge has been something of a perennial problem in the literature. Overshadowed by her father, simply calling her “Coleridge” seems too liable for confusion. Her marriage to a cousin, moreover, left her identity hidden behind his name: “Mrs. Henry Nelson Coleridge” appears on the title page of some of the most influential editions of her father’s works, obscuring her identity in the process. And the overlapping names of her mother, Sarah Coleridge, and the object of her father’s romantic obsession, Sara Hutchinson, only add to the puzzlement many readers feel in sorting out the elusive figures of this remarkable Romantic circle.

Until one day a friend pulled me aside. He explained to me that most of Sara Coleridge’s manuscripts are housed at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. Intrigued, I discovered that several boxes of her letters and unpublished works could be found there. Access. Discovery. Sara come to life as an individual: The poet’s daughter, the little-known writer who served as literary guardian to a father she barely knew.

And so it was that I found myself seated at a long, wooden table in Texas one hot and humid July. Manuscripts carefully laid out. Hoping to move quickly. Working carefully through the Sara Coleridge Collection. There before me I discovered a life I’d never read, never known. Perusing each page of her commonplace books, my eyes scanning letters written to correspondents intimate or remote, I encountered a life unfolding in delicate leaves of poetry, philosophy, theology, and criticism. Past biographies had told her story “exhaustively, sympathetically,” as Virginia Woolf once wrote, but still “dots intervene.”[2] I realized that Sara’s religious work remained almost entirely untouched, requiring researchers with the training necessary to recognize her contribution to the debates of the times and a corresponding interest in her life to be willing to expend the effort.

I felt the weight of the responsibility. Indeed, I followed her to her grave. There had been many deaths before—her twins, a daughter, a husband, her mother—but nothing had prepared me for her own slow decline. She recorded the progress of her illness with breast cancer. She registered her ailments. Her script grew labored, scratched out with blotched ink by a weary hand. Meanwhile, reports from the doctors to “wait and see” elicited within me silent cries of anger and frustration: take it out, take it out! I knew the ending, but my resistance to history could only slow the progress in the measure of each page.

I realized that Sara’s religious work remained almost entirely untouched, requiring researchers with the training necessary to recognize her contribution to the debates of the times and a corresponding interest in her life to be willing to expend the effort.

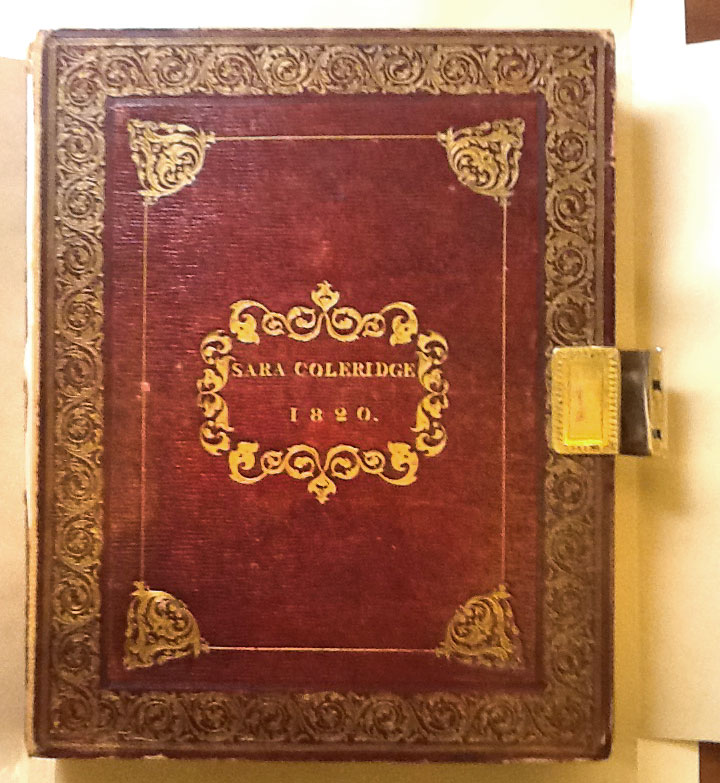

—JEFFREY BARBEAU

With each passing day, I found myself caught up in her story. My focus sharpened. Each record took on new significance, as the narrative of her life eclipsed my awareness of the hours. In the process, I was drawn into the materiality of the archive, no longer satisfied to conceptualize only her ideas. Rather, I became devoted to each object for its own sake. The diary before me was the very same one that once lay open before her. The folds in a letter, mere creases in a page, served as reminders that the words once written were subsequently creased, sealed, and placed in the post—an embodied act of self-giving that I discovered in the stillness of the reading room.

Sara wrote a final poem, knowing her end was near:

Split away, split away, split away, split!

Plague of my life, delay pretermit!

Rapidly, rapidly, rapidly go!

Haste ye to mitigate trouble and woe![3]

Sara’s rush to judgment countered my own efforts to stave off her end. In the process, something had changed within me. What began as a timely research project soon transmuted in the stillness of the archive. Sara was no longer merely a poet’s daughter, a dead writer of disparate critical works of peculiar historical and literary interest. She was a living person.

[1] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Poetical Works, ed. J. C. C. Mays, 3 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 1.1.456 (lines 58–62).

[2] Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, 4 vols. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1967), 3:222.

[3] Sara Coleridge, “Doggrel Charm,” in Sara Coleridge: Collected Poems, ed. Peter Swaab (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2007), 198.