The day-to-day work of a special-collections curator does not leave much time for actually reading manuscripts, despite assumptions to the contrary on the part of outsiders. I sometimes look with envy at researchers who sit with one document for hours at a time. So it was with great anticipation that I set aside time to survey a shipping carton containing drafts of J. M. Coetzee’s 1983 novel Life & Times of Michael K. I chose it because I was halfway through my first reading of this, the writer’s fourth novel and the recipient of his first Booker Prize. After my brief encounter with this novel’s drafts, I could only imagine the rich research potential of the Coetzee archive as a whole.

The novel concerns Michael K, a gardener of unidentified race who may or may not be mentally challenged. When his mother, Anna, becomes ill, he leaves work to care for her. Anna works as a domestic servant for a wealthy couple and lives in a tiny room beneath their expensive apartment in Cape Town. When the city erupts into violent unrest, the wealthy couple flee, and Michael and Anna briefly inhabit their apartment and then begin a long trek to escape the war-ravaged city for the countryside where Anna once lived; I won’t give away the remainder of the story. The portion of the story described above is told in a flat third-person voice, the distanced narration contrasting dramatically with the appalling physical and emotional conditions of the two main characters.

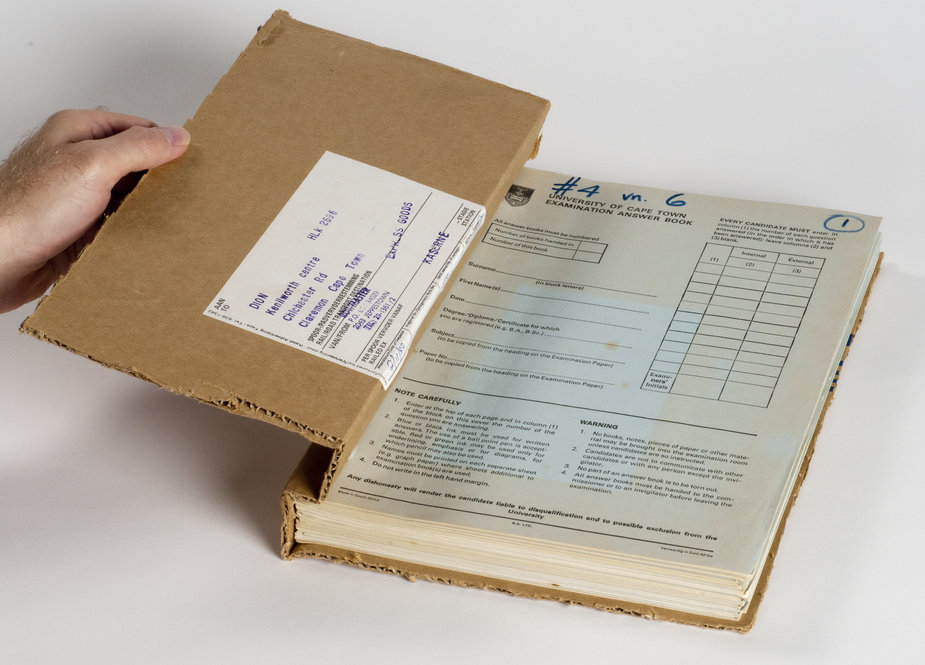

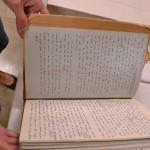

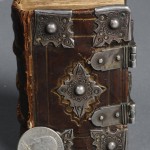

Like the remainder of the Coetzee papers, the drafts of Michael K arrived at the Ransom Center in remarkably good order, carefully arranged by Coetzee (my pleasure in perusing these materials was enhanced by Coetzee’s elegant, eminently legible handwriting—a rare boon for archival researchers). The novel’s nine drafts are held in five hand-bound volumes, and all but the last are titled simply “#4.” Each draft is numbered and bound in sequence. All of the drafts are written (and in one case typed) in one or more yellow or blue University of Cape Town examination books; each of these is likewise carefully numbered and marked with the appropriate version number. Coetzee appears to have bound the volumes together himself, using whatever materials were near at hand: while some are anchored in large file folders using brads, others are bound in large sheets cut from heavy cardboard shipping boxes, held together by hand-cut pieces of thick metal wire bent and pushed through the hole-punched manuscripts. The resulting artifacts have a charm that belies the novelist’s very serious and explicit intent to preserve a linear record of the novel’s composition.

This compositional record is indeed replete with opportunities for scholars of Michael K. The earliest versions of the novel reveal that Coetzee settled upon several foundational elements of the finished novel early on: the characters are named Anna (or Annie) and Michael. They are related. Anna lives in a room on the ground floor of an expensive apartment complex, and her employers flee. She is ill, and Michael comes to help her. Even some wordings in the earliest drafts appear in the finished novel.

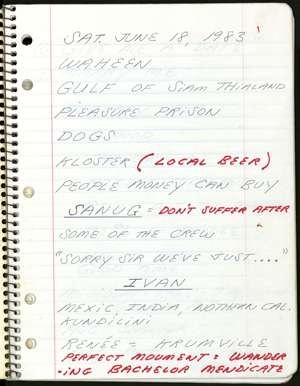

But these similarities are accompanied by profound differences. The first five versions are perhaps best described as windows into alternate realities for the characters of Michael and Anna K, who are reimagined anew by Coetzee as he seeks to determine the nature of the novel’s central relationship. In the first version, Michael is Anna’s son, but he is a brilliant poet, not a gardener who is perceived as dimwitted. In the second, Michael is again her son, but is married and has a child; his wife is killed, and his child taken away before he comes to stay with his mother. In the third, Michael is Anna’s young grandson and worships his absent father (notably, this draft is told entirely in the first person by the child). In the fourth, he is her adult grandson who works as a gardener. In the fifth version, he is Anna’s common-law husband.

Only in the sixth version does Coetzee settle upon the published relationship; this heavily annotated draft is much longer than the ones that precede it and appears to mark a major shift in the compositional process. I skimmed through the later drafts and found further interesting changes too numerous to mention here, but found myself repeatedly returning to the variant Michaels and Annas, wondering how many further variations Coetzee may have considered, and wondering, too, at the elements that he apparently never doubted. For instance, he knew from the beginning that Anna’s legs would be swollen—this detail is described in grim detail in the published novel and appears often in the early drafts—but did not know whether the woman’s son, grandson, or husband would cope with this ailment.

The Annas and Michaels have stayed with me, and I have already started reading the novel again from the first page, seeking traces of those lost characters and viewing the swollen legs, the room beneath the apartment, and the names “Anna” and “Michael” with fresh attention.

Please click the thumbnails to view larger images.