Presenting a costume or historical clothing on a mannequin may seem deceptively simple at first glance. Yet there is rarely an instance of a mannequin, standardized or made-to-measure, that is ready to use “out-of-the-box.” Each area of the body—shoulders, torso, arms, legs, and feet—must be customized and often requires several fittings with the garment. This is similar to the process of fitting a made-to-order garment to a human body, although in this case the process is reversed as the mannequin must be shaped and conform to the garment.

A World War I uniform, from the collection of the Texas Military Forces Museum and currently on display in The World at War, 1914–1918, presented us with a particular challenge. The physique of most modern, full-body mannequins is too tall, muscular, and athletic for early twentieth-century clothing and footwear. The size of the mannequin must always be smaller than the measurements of the costume to allow for supportive padding and to prevent any stress or strain on the costume when dressing or on display. We made the decision to pad up an adolescent/teenage dress form that was already in our inventory and to construct realistic-looking legs, a crucial element in presenting the ensemble successfully.

This was our first time to use Fosshape, a polyester polymer material often used for theater costume design or millinery. Textile conservators have recently explored and used Fosshape for museum display, and we decided to use this flexible, adaptable material to construct the legs. An approximate tapered “leg” shape was cut, sewn, and placed over the calves and ankles of a full-body mannequin to get a realistic leg shape. When steam heat is applied to the Fosshape, it reacts, shrinks, and hardens to the shape of the mold beneath.

Because the leg dimensions of this particular mannequin were too large to safely fit through the narrow hem of the uniform jodhpurs, we had to “take in” the legs to a smaller circumference, while still retaining an accurate calf and knee shape. Because the definition was lessened somewhat, we made “knee” and “calf” pads to help support and define the shape of these areas. Additional Fosshape pieces were created and steamed to provide more structure and interior support.

The legs were adjusted accordingly and covered with a smooth polyester fabric to aid with dressing, and pieces of velcro were sewn to the inside of the Fosshape legs and the exterior of the mannequin legs for easy attachment.

Arm patterns, taken from an excellent resource on mannequin creation and modification, A Practical Guide to Costume Mounting by Lara Flecker, were modified to fit the length and curvature of the jacket’s arms. Once sewn, the arms were filled with soft polyester batting and sewn to the mannequin’s shoulders. The chest and back were padded out where needed, and a flesh-colored finishing fabric was cut, sewn, and secured to the mannequin’s neck.

The final crucial details were aligning and orienting two twin silver mannequin stands so that they would reflect a natural body stance once the legs and boots were placed. Additionally, the stands were covered with a matte black fabric, so the high shine of the silver bases would not distract from the uniform. Once the stand was correctly aligned and covered, dressing the mannequin could begin.

Constructing, modifying, or dressing a mannequin is never a solitary endeavor. This entire process was a collaboration between the curator of costumes and personal effects and conservation and exhibitions staff. Colleagues Mary Baughman, Ken Grant, Apryl Voskamp, and John Wright were invaluable with their help and expertise.

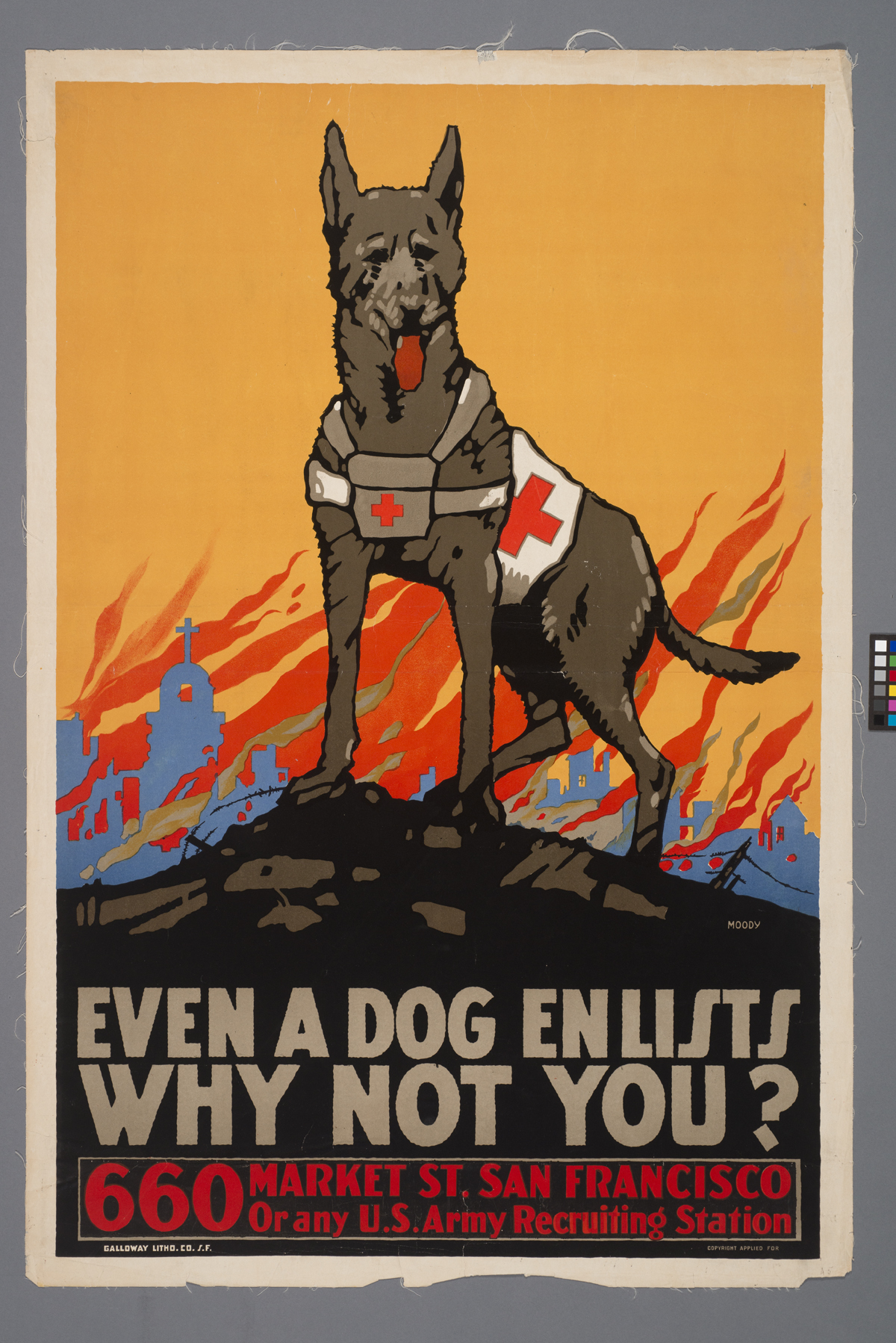

Top image: World War I uniform on display in Ransom Center’s exhibition The World at War, 1914-1918. Photo by Pete Smith. Please click on thumbnails below to view larger images.

![Sem (1863–1934). “Pour la liberté du monde. Souscrivez á l'Emprunt National á la Banque Nationale de Crédit.” [For the freedom of the world. Subscribe to the National Loan at the Banque Nationale de Crédit.] 1917. Lithograph. 119 x 77 cm.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2014/04/85_130_515_001.jpg)

![Unknown artist. “Soglasie” (“согласие”). 1915. [Agreement or Triple Entente]. Lithograph. 71 x 54 cm.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2014/04/85_85_40-150x150.jpg)

![Sem (1863–1934). “Pour la liberté du monde. Souscrivez á l'Emprunt National á la Banque Nationale de Crédit.” [For the freedom of the world. Subscribe to the National Loan at the Banque Nationale de Crédit.] 1917. Lithograph. 119 x 77 cm.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2014/04/85_130_515_001-150x150.jpg)