I. Artist: The Farnese Hercules is credited to be carved by a sculptor named Glycon of Athens. Although there is no mention of Glycon in ancient writing, it is believed that he lived in the period between Lysippus and the early Roman emperors. Lysippus is credited to creating the Heracles of Sicyon, a bronze statue that art historians believe to be the

inspiration for Glycon’s Farnese Hercules. The name of the artist is carved into the main

support of the statue, and the inclusion of the Omega in Glycon’s name, a feature not

used in inscriptions until shortly before the Christian era, solidifies the time period

Glycon might have lived.

II. Date: The original Farnese Hercules was created in the 3rd century AD. The replicated statue displayed at the H.J Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports was created sometime between 2007 and 2009. According to the Stark Center’s webpage, “the Stark Center’s Farnese Hercules was made from a mold taken from the original Farnese Hercules at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples, Italy in approximately 1900.”

III. Location: A copy of Glycon’s Farnese Hercules is currently on display at the entrance of the H.J Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports located in the Darrel K. Royal Texas Memorial Stadium on the University of Texas campus.

IV. Acquisition: The Stark Center Directors, Drs. Jan and Terry Todd, both admirers of Glycon’s sculpture, adopted the symbol of Hercules to emphasize their emblem of strength, determination, and commitment. With knowledge that the Royal Museum for Art and History in Belgium was capable of casting replicas of the Farnese Hercules, the directors commissioned for a statue to be copied for the Stark Center. The Stark Center’s Farnese Hercules was molded from the original Glycon sculpture, now located at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples, Italy. In June of 2009, the replica was shipped in four large crates, and in August 2009, Hercules was assembled and installed in the Stark

Center by two artists from the Atelier. The Stark Center contains a library, archives, and

museum dedicated to the study of physical culture and sports. In the context of the

athletic world, literature on strength training and sports, and awards for Longhorn and

Olympic victories, the Farnese Hercules is a symbol for the modern athlete. According to

Terry Todd, the Farnese Hercules is at the Stark Center to serve as a reminder of the

importance of physical culture in human culture. At the Stark Center, the Farnese can be

perceived as the physique modern athletes and people can achieve.

V. Description: The Farnese Hercules carved by Glycon of Athens is a ten and half foot marble statue. Since the replica displayed at the Stark Center is molded from the original statue, the replica is of the same stature as the original. The statue portrays a tired Hercules leaning on his club. The skin of the Nemean Lion is draped over the club, signifying that the Greek hero is resting. Other indications of Hercules’ weariness is his downward gaze and relaxed left hand. In his right hand, mysteriously held behind his back, are the Golden Apples of Hesperides. This inclusion in the sculpture, along with the state the hero is portrayed to be in, signifies Hercules has just completed his eleventh labor.

The classical mythological elements included in this statue are the Nemean Lion skin, the

club, and most significantly the Golden Apples of Hesperides. According to myth,

Hercules had to serve King Eurystheus as a way of purifying himself. For his first labor,

Hercules was sent to kill the Nemean lion, a monster with impenetrable skin. Hercules

succeeded by choking out the beast. (Apollodorus, Library, 34). After his success, the

skin animal can be seen as worn armor for the hero. Eurystheus assigned the Hercules ten

labors, but he added two more after being unsatisfied with Hercules’ completion of two

prior labors. For his eleventh labor, the king ordered Hercules to obtain the Golden

Apples of Hesperides from Mount Atlas in the land of the Hyperboreans. This location

was practically unknown and a great trek for any mortal man. The Apples were a

wedding gift for Hera from Gaia, and in addition to being at the western edge of the

world, the Golden Apples were guarded by an immortal serpent with one hundred heads

and the Hesperides. Hercules travelled far, coming across other challenges on his journey,

to reach the Golden Apples. Before reaching his destination, Hercules was advised by

Promthesues, after saving him from his eternal punishment, to send Atlas, the god

holding up the sky, to obtain the apples for him. To do this Hercules offered Atlas he’d

hold the sky in return. However, after retrieving the Apples, Atlas plotted to leave

Hercules in his place. With quick thinking, Hercules tricked Atlas into holding up the sky

again and leaving with the Apples. Other myths say Hercules himself retrieved the

Apples from the serpent (Apollodorus, Library, 39-40). However the myth of Hercules’

eleventh labor is expressed, it is evident that he travelled far and faced adversities on his

journey to the Hesperides. This weariness is therefore accurately portrayed in the statue

carved by Glycon. The Farnese Hercules clearly holds a mythological context with its

presence. The posture of the hero and the inclusions of elements from the twelve labors

support how Glycon’s statue is an artwork that tells a story about enormous burden. From

a real world perspective, The Farnese Hercules holds a symbol of athleticism, strength,

and physical health. The original Farnese Hercules was discovered in the ruins of the

Baths of Caracalla in 1546, and it is believed that the statue served as one of the many

artworks that decorated the public baths in Rome. In Ancient Roman culture, public baths

were symbols of community and health. These baths were connected to gymnasiums and

included libraries containing Greek and Roman literature. In essence, the Roman baths

were places where one could better themselves mentally and physically. It’s no surprise

that a statue of Hercules was most likely commissioned to be made as decor for these

baths since Hercules can be perceived as a symbol of physical health, athleticism, and

strength of mind and body, all attributes the Roman baths, and gymnasiums connected,

centralized. Overall the symbolic meaning of the Farnese Hercules can be a combination

from its mythological context and original location in Rome. The mythological aspect of

the statue depicts a hero who has gone to extreme lengths to finish his task, embodying a

sense of accomplishment at the expense of physical strain. In a way this interpretation

can also be translated into modern symbolism of Hercules as an embodiment of human

body physical achievement and athleticism. For the modern human, achieving a physique

like Hercules is an accomplishment that comes at the expense of physical strain.

Similarly, athletes accomplish their victories at the expense of many sacrifices. These

interpretations of the Farnese Hercules support why Drs. Jan and Terry Todd wanted a

replica of the statue at Stark Center, an area for athletic achievement and overall physical

health accomplishment.

Bibliography

“APOLLODORUS, THE LIBRARY 2.” APOLLODORUS, THE LIBRARY BOOK 2 –

Theoi Classical Texts Library. Accessed May 1, 2021.

https://www.theoi.com/Text/Apollodorus2.html#Heracles.

“A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology William Smith, Ed.” A

Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Gabaeus, Glaucon, Glycon.

Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0104%3Aalph

abetic%2Bletter%3DG%3Aentry%2Bgroup%3D8%3Aentry%3Dglycon-bio-7.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, Dr. Beth Harris, and Dr. Steven Zucker. “Lysippos,

Farnese Hercules.” Smarthistory. Accessed May 1, 2021.

https://smarthistory.org/lysippos-farnese-hercules/.

“The Farnese Hercules.” H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports.

Accessed May 1, 2021. https://starkcenter.org/about/the-farnese-hercules/.

“Rome, Baths of Caracalla.” Livius. Accessed May 1, 2021.

https://www.livius.org/articles/place/rome/rome-photos/rome-baths-of-caracalla/.

Trzaskoma, Stephen M., R. Scott Smith, Stephen Brunet, and Thomas G. Palaima.

Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation, n.d.

“Visitors.” H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports, February 12, 2020.

https://starkcenter.org/2009/10/visitors/.

Vermeule, Cornelius. “The Weary Herakles of Lysippos.” American Journal of

Archaeology 79, no. 4 (1975): 323-32. Accessed May 1, 2021. doi:10.2307/503065.

Author: Michael Anthony

One of my former students sent me some pictures of the mythological artwork that she encountered on her visit to the Musée du Louvre in Paris. This marble statue of Eros (Roman Cupid) and a Centaur is one of pieces of Greco-Roman artwork that caught her attention. This famous statue is believed to be a 2nd-century-AD, Roman copy of Greek statue by a sculptor of Aphrodisias. It is a good example of a piece of Greco-Roman artwork for which there is no myth in Greek and Latin literature that we can used to interpret this statue. Therefore, it is unclear as to why the centaur’s hands appear to be tied behind his back, and more interestingly, why is Eros teasing this centaur in the first place.

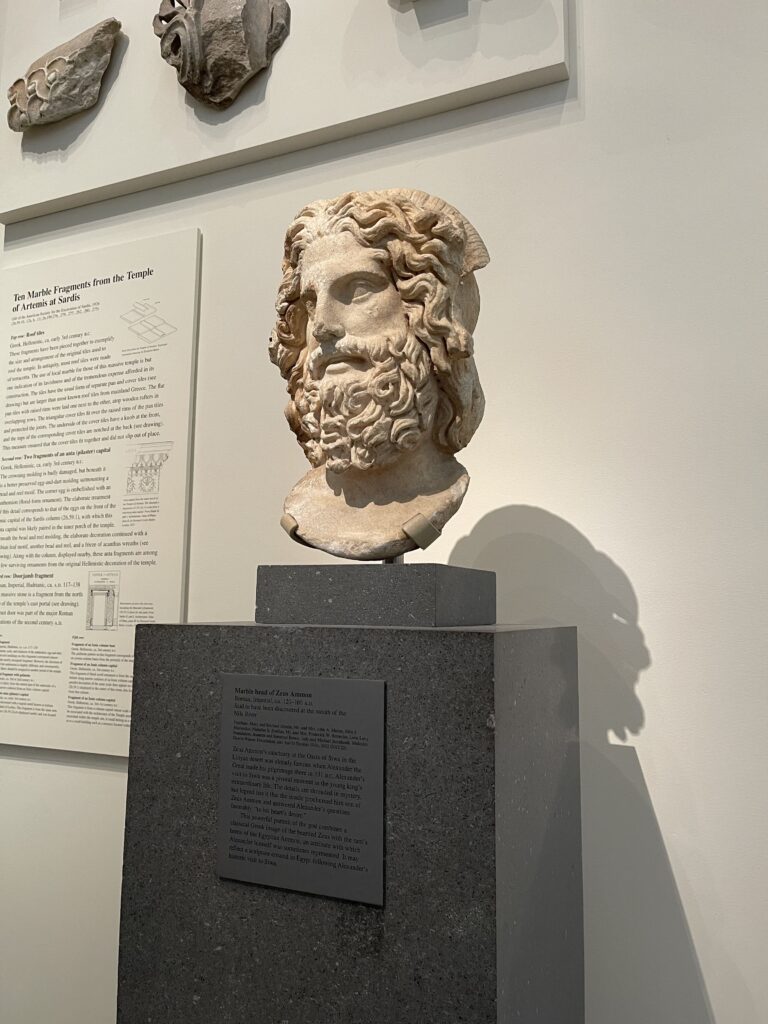

One of my former students sent me some pictures of the mythological artwork that she encountered on her visit to the Musée du Louvre in Paris. This marble statue of Eros (Roman Cupid) and a Centaur is one of pieces of Greco-Roman artwork that caught her attention. This famous statue is believed to be a 2nd-century-AD, Roman copy of Greek statue by a sculptor of Aphrodisias. It is a good example of a piece of Greco-Roman artwork for which there is no myth in Greek and Latin literature that we can used to interpret this statue. Therefore, it is unclear as to why the centaur’s hands appear to be tied behind his back, and more interestingly, why is Eros teasing this centaur in the first place. A quick thanks to one of my former students for sending me this personal photo of a 2nd-century-AD marble head of

A quick thanks to one of my former students for sending me this personal photo of a 2nd-century-AD marble head of

I. Artist: This work is attributed to an Athenian red-figure vase-painter, whose name is uncertain. However, the painter’s name is thought to be Pig Painter, a name that was inspired by images of swineherds that the artist painted on pelike, which is currently located in the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge. Certain stylistic characteristics have led to a belief that this artistic identity has also done several other vases throughout 480 BC-460 BC. [1}

I. Artist: This work is attributed to an Athenian red-figure vase-painter, whose name is uncertain. However, the painter’s name is thought to be Pig Painter, a name that was inspired by images of swineherds that the artist painted on pelike, which is currently located in the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge. Certain stylistic characteristics have led to a belief that this artistic identity has also done several other vases throughout 480 BC-460 BC. [1}