![]() Download the PDF (561 KB)

Download the PDF (561 KB)

Read on Texas Scholar Works

By Denise Schmandt-Besserat

Abstract: This final part of the chapter devoted to the ‘Ain Ghazal plaster statuary excavated in 1983 and 1985 focuses on the style. The analysis includes: (1) a definition of the genre, (2) its evolution between 6750-6500 bc, (3) a comparison with other anthropomorphic representations at the site, (4) a comparison with similar contemporaneous assemblages in the Levant, (5) a review of the possible origin of the PPNB statuary. The paper also assesses the three common interpretations of the statues—ancestors, ghosts, or deities. Finally, the conclusion evaluates the significance of monumental plastic art.

Key Words: sculpture in the round, statuary, busts, plaster, dying gods.

The ‘Ain Ghazal Plaster Statuary

As fully discussed above by C.A. Grissom, the thirty-two statues of ‘Ain Ghazal were located in two separate caches. Cache 1 (6750 +/- 80 bc), found in 1983 (Rollefson and Simmons 1985: 48-50), yielded twenty-five pieces including thirteen full-size statues and twelve one-headed busts, of which three statues and four busts are now restored (Tubb and Grissom 1995: 443-447). As for Cache 2, excavated in 1985 (Rollefson and Simmons 1987: 95-96), five of its seven statues are now back to a good state of repair (Grissom 1996). The collection consists of two full statues, three two-headed busts, and two fragmentary heads. This second cache is estimated to date about 6570 +/- 110 bc, or possibly as late as 6500-6400 bc, the first two centuries of the LPPNB (Rollefson 2008b: 81). In the first part of the paper, I identify the basic characteristics of the ‘Ain Ghazal PPNB statuary. I lay out the features that remained constant from 6700 to 6500 bc, the two centuries that may separate the two caches.

The ‘Ain Ghazal statues share the following traits:

- All are anthropomorphic. They consist either of full figures or busts. The latter may be one- or twoheaded (see Grissom, chapter 5.3).

- They belonged to identical archaeological contexts and were carefully laid in a pit visibly dug for the sole purpose of their disposal. The two caches were buried beneath the floors of long abandoned houses. In other words, they were not under habitation floors but were segregated from the living.

- Their general orientation was east-west (except for the busts of Cache 1 laid crosswise below the statues).

- They were seemingly in a good state of preservation when they were buried (except for two fragmentary heads and pieces of statues that may have been broken when deposited).

- The surface of the statues consists of plaster. Otherwise utilized to cover house walls and floors (Kingery et al. 1988), for tokens (Iceland, chapter 2.1.), and in the funerary custom of modeling skulls, lime plaster used for statuary in the round was an innovation.

- Their manufacture involved a reed armature. As described for Grissom for Cache 2 in Chapter 7.1, head(s), torso, and legs were built around separate reed bundles bound with twine and covered with a thick layer of fresh plaster. Then the parts were assembled with a final modeling at the joints.

- They are large. Compared to the contemporaneous Neolithic, minuscule human clay or stone figurines found at the site, the 35-100 cm high statues may be termed monumental.

- Their thickness is about 5-10 cm. In other words, the figures are flat, almost two dimensional. The back is straight except for slightly projecting buttocks.

- The full statues are balanced in order to stand up. The busts have hand-smoothed flat bases.

- The genitalia are systematically omitted, except perhaps for one figure that might be depicted with pudenda (Pl. 7.3.1b). Breasts are sometimes shown (Pls. 7.3.1a-b).

- The head is emphasized. It represents about one-fifth of the total size of the earlier statues, one-sixth in the later ones, and two-fifths of the 1983 and one-fifth of the 1985 busts, respectively. The neck is oversized.

- A recessed feature is set above the forehead.

- The visage is treated with ochre and given a silky finish. The stylization involves manipulating the proportions of the human face (see Grissom, chapter 7.1). The high forehead is about half the size of the head. The eyes are placed far below the brows. The cheekbones are low compared to the base of the nose. The brows, nose, labial canal, and mouth are arranged in a T-shape. The mouth and the base of the nose are the same size. The ears are high, close to the eyes, and sometimes above their level.

- The facial features are striking. The nose is conspicuously short and upturned, exhibiting long, thin nostrils. The minuscule mouth has no lips.

- Lastly, they have the same arresting glance. The eyes are disproportionately large—twice the size of base of the nose and many times that of the mouth. They are set far apart. The globe bulges slightly, surrounded by a deep, oval ridge filled with black bitumen. The lids are not portrayed.

There can be no doubt that the two sets of statues—which shared location, orientation, material, technique and style—are parallel manifestations of the same monumental statuary that prevailed at ‘Ain Ghazal from 6750 to ca. 6500 bc. The figures departed from the former anthropomorphic figurines of the Khiamian (PPNA) culture (Bar-Yosef 1980) by using perishable vegetable material and plaster instead of stone and, especially, by their monumental size.

The Evolution Of The Statuary

This section focuses on the developments that took place in the statuary over two or three centuries of their usage, ca. 6700-6500 bc. I point out the traits that distinguish the earlier figures from the later ones.

First, the number of statues seems to fluctuate over time. The earlier cache had a record twenty-five pieces, among them thirteen full figures and twelve one-headed busts. Cache 2 yielded only seven statues, including two full figures, three two-headed busts, and two as yet unidentified pieces. It should be kept in mind, however, that the later cache was severely damaged by bulldozers and might originally have held more pieces.

The two caches vary also in the types of statues they held. The introduction of the two-headed busts constitutes the most significant innovation of Cache 2 (see Grissom, chapter 7.1).

The size of the statuary increased from 6700 to 6500 bc. The largest full figures of Cache 1 measure about 84 cm, compared to 1 m for those of Cache 2. The size discrepancy between the two caches’ sets of busts is even greater. The early one-headed specimens are about 35 cm high, whereas the later two-headed ones reach 88 cm. In fact, the smallest example of Cache 2 is 11 cm taller than the largest of Cache 1. The larger size of the Cache 2 figures is probably responsible for their more complex armature described by Grissom.

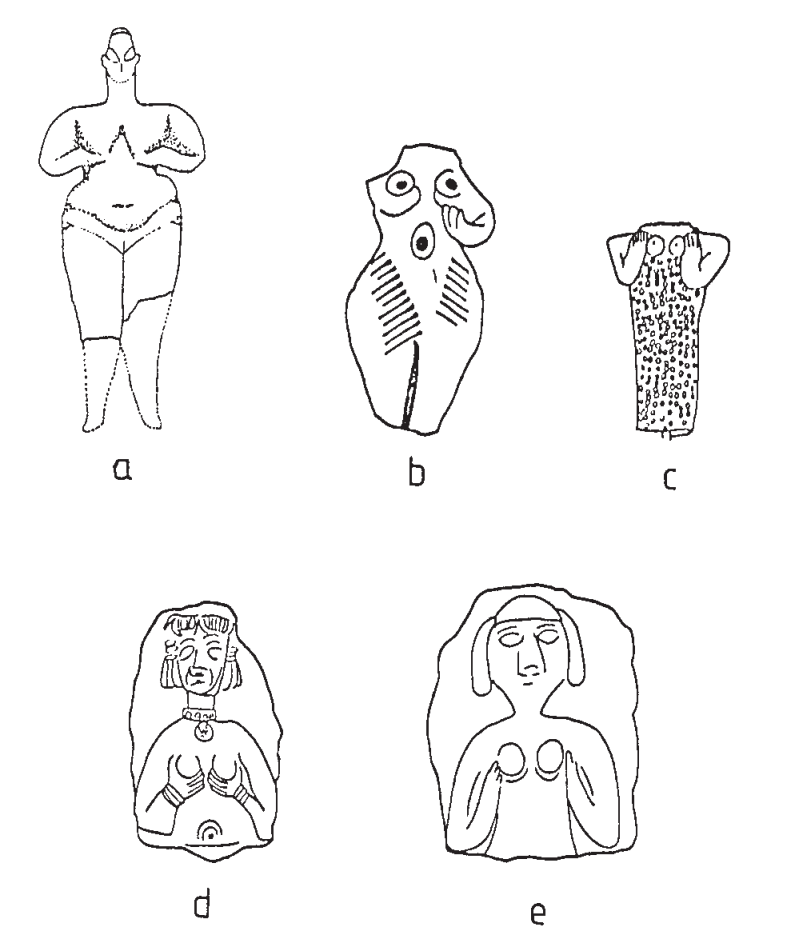

There is a notable trend towards standardization. The figures of Cache 1 have individual facial features and assume varied positions. For example, one figure has straight arms (Pl. 7.3.1c), whereas others bend theirs in different ways (Pls. 7.3.1a and b). In contrast, the figures of Cache 2 have almost identical faces and posture.

The torso became more schematic. In Cache 1, the shoulders are carefully modeled, sloping gently. The waist is clearly marked and the pelvis and buttocks are sensitively rendered, including in one figure a light bulge suggesting fat around the thighs (Pl. 7.3.1a). One statue of Cache 1 has breasts placed low in the center of the chest (Pl. 7.3.1a), and a second displays udder-like features (Pl. 7.3.1b). But in Cache 2 the torso is reduced to a rectangle, the figures do not have waists, and the breasts are never displayed (see Grissom, chapter 7.1).

The arms, small and withered in the statues of Cache 1 fully disappear in those of Cache 2. One of the earlier figures has straight stick-like arms, with no indication of elbows or wrists, and fully disproportionate to the torso (Pl. 7.3.1c). A second, which will serve as an important clue for the function of the figures, bends her arms to hold her breasts (Pl. 7.3.1a). Her skimpy upper limbs are devoid of forearms and end in fan-shaped hands. The same gesture is repeated by another figure, although more schematically (Pl. 7.3.1b). Here, the arms are reduced to thin, crescent-shaped stumps curving towards the breasts. In this last instance no fingers are indicated, but in the two statues described above, digits are cursorily cut in the plaster by straight slashes. The number of fingers seems not to matter. One statue has four on the left hand and five on the right (Pl. 7.3.1c) and another has a right hand with seven fingers (Pl. 7.3.1a). The statues of Cache 2 have no arms or hands (see Grissom, chapter 7.1).

The legs of the later figures also received a lesser treatment. In Cache 1, they extend organically from the torso, tapering from the thigh to the knee, calf, and ankle. But in Cache 2, the legs are separated from the torso by a schematic groove. The projecting kneecaps translate the difference of thickness between the taut thighs and the calves. Feet are not preserved on the statues of Cache 1, except for a detached fragment that, peculiarly, shows six toes (Rollefson 1983: 36). In Cache 2, the statues have short and wide feet. The toes are cut with slashes of inconsistent lengths extending through half of the feet. The toenails, however, are carefully indicated.

Painting, widely used in the earlier statues, is reduced in the later ones. The statues of Cache 1 were treated with ochre before being smoothed. One head had sets of three stripes on the forehead and on each cheek. One figure is covered in front with a pattern of red, vertical lines along the thighs and legs that ends in a black, horizontal, broad band circling over the ankle (Pl. 7.3.1c). Another bears traces of a similar red design around the stomach and legs (Pl. 7.3.1b) and, in addition, these two statues were painted around the shoulders. In both of these figures, the intention may well have been to feature pants and bodices. Traces of pigment are limited to the face in the other set. There is no paint on the torsos of Cache 2.

The busts underwent the same stylization. Whereas in Cache 1 the single head extends naturally from a carefully smoothed, human-shaped torso (Pl. 7.3.1d), in Cache 2 the two heads awkwardly project in front of the bust (see Grissom, chapter 7.1).

Contrary to the rest of the body, the visage remains unchanged except in details. The statues of Cache 2 have almond-shaped eyes, sometimes slanting inwardly (see Grissom, chapter 7.1); a more pointed nose in the shape of a tetrahedron; ring-shaped ears; and a cleft chin (see Grissom, chapter 7.1). Those of Cache 1 have rounder eyes painted with a thin filament of an intense green pigment, with the surrounding black-bitumen ridge often left open at the corners, a blunt nose, lug-shaped ears, and a round chin. The most singular shift is in the treatment of the iris. In Cache 1 it is round—as it is in nature. Indeed, although all human races are characterized by a specific eye shape, they share an absolutely circular iris and pupil; likewise, whereas each individual has facial features that make him or her unique, all humans have a perfectly circular iris and pupil. But the ‘Ain Ghazal figures of Cache 2 have a diamond-shaped iris or pupil. While their bodies are anthropomorphic, their eyes are not.

The large statuary of ‘Ain Ghazal evolved between 6750 and 6570 bc, over two or three hundred years. The main changes consisted of: (1) a possible fluctuation in the number of figures, from twenty-five to seven; (2) the appearance of two-headed busts; (3) a greater stylization; and (4) diamond-shaped iris or pupils, which conveyed to the statues of Cache 2 an eerie, alien, or feline look, distinguishing them from the more benign figures of Cache 1. The fact that the statues and busts grew taller may be the most noteworthy feature. This may mean that the size or monumental quality of the statues increased in importance over time.

Anthropomorphic Parallels at ‘Ain Ghazal

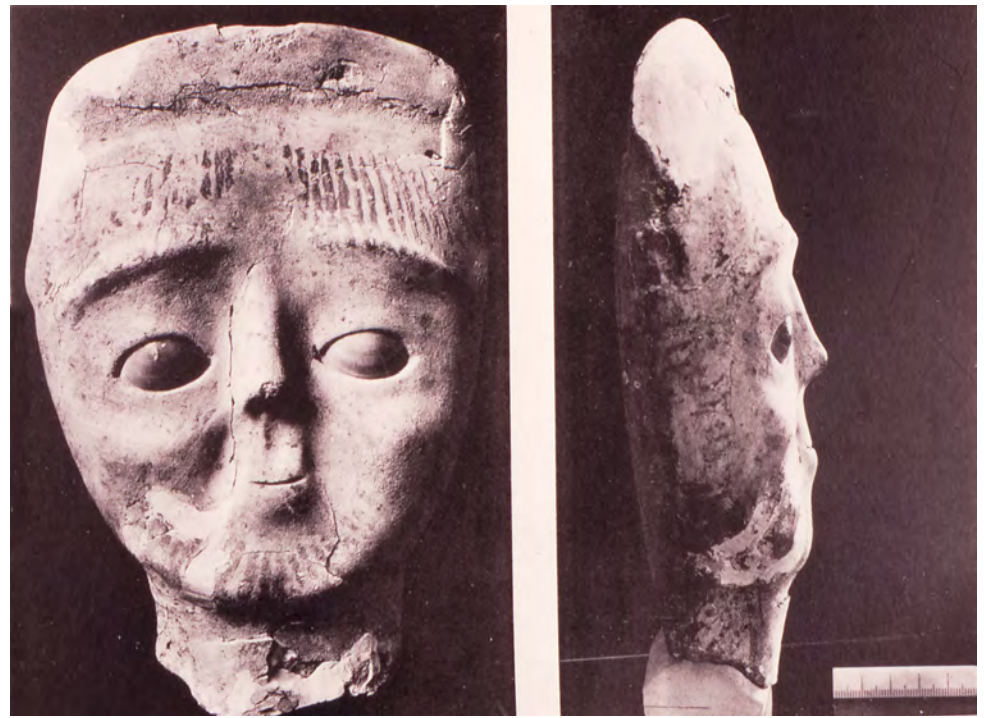

Stylistically and in size, plastered skulls are the closest objects to the statues in the ‘Ain Ghazal assemblage (see Schmandt-Besserat, chapter 6.2). The artifacts were made by removing the flesh and lower jaw from a human skull, covering it with plaster and modeling the forehead, brows, eyes, nose, mouth, and chin. Six plastered skulls were excavated at ‘Ain Ghazal: two damaged examples in 1983 (Rollefson and Simmons 1985: 47); a group of three masks, no longer attached to the cranial bones in 1985 (see Grissom, chapter 6.1) (Rollefson and Simmons 1987: 94-95); and one, fairly well preserved, in 1988 (Simmons and Boulton, et al. 1990). All belong to the PPNB period. The oldest three specimens excavated in 1985 are as early as the 8th millennium bc, since they were located below a floor dated 7100 bc, and the latest, found in 1985, is as late as ca. 6500 bc.

Unlike the statues, the plastered skulls were not buried in abandoned quarters. The group of three masks was located in an outdoor pit dug in virgin soil. The 1988 piece was located beneath the northern end of a painted plaster floor of a house (Simmons and Boulton, et al. 1990: 108).

The modeled skulls shared some of the stylistic features of the statuary. Namely, the 1988 specimen has the characteristic upturned nose with conspicuous nostrils and the elongated eyes of the Cache 2 statues. The three 1985 skulls treat the brows and mouth in an identical way. Of course, the fact that the chin was modeled over the upper teeth changes the proportions of the visage, giving it a puffy look. In the three masks the swollen eyelids, defined by a line of bitumen, are tightly shut, creating an important departure from the open-eyed statues.

The skulls constitute important parallels to the plaster figures. Both types of artifacts share the same large size and are modeled with plaster in a comparable style. The similarities as well as differences between the two genres may prove revealing (Rollefson 2008a: 401).

Parallel Plaster Statuary In The Levant

Excavations in the PPNB layer of the cave of Nahal Hemar, Israel, which is dated to ca. 6300 bc, produced small pieces of lime plaster showing the imprint of reeds and traces of paint and burnishing (Bar-Yosef and Alon 1988: 20-21). Two were head fragments decorated with a molded net-pattern. A third piece depicts an eye stained with green pigment and surrounded by an oval line of black bitumen. The small quantity and poor preservation of the fragments precludes an in-depth stylistic comparison with the Jordanian material. Analysis of the material showed, however, that they belonged to at least four figures apparently similar to the ‘Ain Ghazal type of statuary but each differing in material composition. Surprisingly, the substances involved in one of the statues point to a possible origin on the Mediterranean coast (Goren et al. 1993: 127).

The 1935 and 1955-1956 campaigns at Jericho, Palestine, led respectively by Garstang (1935) and Kenyon (1957: 84), located PPNB pits dated to ca. 6700-6500 bc with quantities of plaster pieces (Kingery et al. 1990: 233; Goren and Segal 1995: 163) painted with red and cream stripes. Some fragments bear the imprints of reeds reminiscent of the ‘Ain Ghazal armature (Amiran 1962: 23-24), but most had a core consisting of coarse crumbly marl (Goren and Segal 1995: 163). Diagnostic pieces, such as segments of legs and shoulders or a flat base, show that the two caches of statues excavated by Garstang yielded full figures and busts, but here also the fragments are poorly preserved, limiting the possibility for a thorough stylistic analysis (Moorey 2005: 33). What can be said is that the fragment of a foot with six toes provides a parallel to that of Cache 1 in ‘Ain Ghazal. The best-preserved piece in the Garstang collection consists of a flat head topped with a recessed feature and painted with red lines over the forehead, cheeks, and chin as familiar in Cache 1 (Fig. 7.3.1) (Garstang and Garstang 1948: 66-67). The brows, upturned nose, prominent nostrils, long labial canal, cleft chin and puckered, lip-less mouth are like those of the ‘Ain Ghazal statues. The eyes of the Jericho head, however, were represented by glossy shells inserted below the brows, imitating the shiny texture of the cornea.

The two sites also produced modeled skulls. At Nahal Hemar, three skulls were decorated at the back with the same net pattern noted on the statuary fragments of the site; however, in this case, the motif was molded with a collagen substance rather than bitumen (see Schmandt-Besserat, chapter 6.2, Fig. 6.2.7) (Nissenbaum 1997). Like the head of the statue found by Garstang, the ten modeled skulls excavated by Kenyon in Jericho in 1953 used shells to represent the eyes. In this case, however, the shells were segmented to suggest a vertical pupil (Kenyon 1957: 60-64).

Nahal Hemar and Jericho did not produce the same array of well-preserved statues as did ‘Ain Ghazal. Nonetheless, the two sites are invaluable in demonstrating that the monumental statuary and plastered skulls traditions were shared by other PPNB settlements (Rollefson and Kafafi 2007: 215). The green pigment at Nahal Hemar, and both the red designs and the foot with six toes at Jericho, tie the two Cisjordanian statue assemblages to the style of Cache 1 at ‘Ain Ghazal.

The PPNB Levantine Plaster Statuary

The material from the three sites discussed above give an insight into the origin of monumental plastic art in the Levant. ‘Ain Ghazal and Jericho reveal that large statuary flourished in PPNB Jordan as early as the beginning of the 7th millennium bc. Nahal Hemar provides the evidence that the genre continued for at least four centuries, until ca. 6300 bc. The large statues were in use in an area of some 150 km on either side of the Jordan River and to the northeast, northwest, and southeast of the Dead Sea, and as suggested by the raw material of some of the Nahal Hemar fragments, perhaps as far as the Mediterranean shores (Hole 2000: 207). The special material composition and stylistic features illustrated at Jericho and Nahal Hemar illustrate that communities developed their own ways for the basic manufacture and decoration of the figures (Yakar and Herskovitz 1988; Goren and Segal 1995: 164). Plastic art in the round seems to follow the custom of modeling human skulls since plastered skulls are attested as early as 7100 bc both in ‘Ain Ghazal and Jericho. The limited evidence allows no more than conjecture that plaster statuary started declining by 6500 bc, when the number of figures dwindled at ‘Ain Ghazal, perhaps already presaging their complete disappearance after 6300 bc in the following PPNC. Therefore, the phenomenon can be connected to sedentary farming since the monumental statuary developed parallel to the domestication of plants and animals and did not survive the mixed economy based on nomadic pastoralism and agriculture in the PPNC period.

The consistent way of manufacturing and disposing of the statues over two or three hundred years suggests that they always served the same purpose. Their function was visibly not intended to last for eternity since the figures were not made of stone, like the previous PPNA sculptures, but with perishable vegetable material. Their purpose was also probably ephemeral since the repeated caches make it conceivable that the statues were discarded immediately after use apparently because once their purpose was fulfilled, they were no longer needed. The facts that the know-how of building the figures with reeds and plaster was never lost and that the unusual facial features were never forgotten imply that for over twenty generations the icons were possibly made at regular and frequent, perhaps seasonal, intervals.

The quantum jump in size from the PPNA figurines to the large PPNB statues must be significant (Kuijt and Chesson 2007: 221). It must imply that plastic art played a new role. The minuscule, Neolithic clay females belonged to homes, but the large statues suggest a public display. The well-balanced figures and the flat-based busts indicate that the effigies were not laid flat but were exhibited in an upright position (Rollefson 2005: 6). Because they had no depth, the icons were probably presented frontally. The feature above the forehead is generally interpreted as holding a headdress made of a different material than the figure (Gunther 1996). This interpretation suggests that the custom of adding on garments to the statues may have become more popular over time, replacing the bodice and pants painted on the early figures and even substituting sleeves for the former modeling of the arms. This practice would explain why the torso and limbs became ruthlessly stylized, whereas the face and toes continued to be carefully finished. The shape or color of the garments perhaps identified the gender of the figure, accounting for the general lack of sexual dimorphism. The idea of add-on headdresses and garments is particularly appealing because the custom seems well attested in the later statuary, such as at Tell Brak, Syria (Spycket 1981: 38), and Uruk, Mesopotamia, in the 4th millennium bc (Spycket 1981: 36-37).

A picture of the origin of monumental statuary emerges. The analysis of the ‘Ain Ghazal, Nahal Hemar, and Jericho figures defines the place and time when the phenomenon took place, its relation with farming, the types of statues it involved and the way the statues were displayed. Can the archaeological data also break the symbolic code and thereby gauge the significance of the new art? In other words, can we find out for whom the icons with big eyes, upturned nose, long nostrils, and puckered mouth stood and their role in the PPNB communities?

Ancestors? Ghosts? Or Dying Gods?

A customary interpretation for the statues, namely that they portrayed venerated ancestors, may be first credited to Kenyon (1957: 85). Comparing the Jericho plastered skulls to ethnographic data, she reasoned that the artifacts could be either honoring ancestors or representing slain enemies (Kenyon 1957: 62-63). She further noted that the Jericho statues and plastered skulls had common features, such as the use of shells in lieu of eyes (Kenyon 1957: 84). She then hinted at the hypothesis that both genres could be related to a similar death ritual. The finds at Nahal Hemar and ‘Ain Ghazal strengthened the idea of a link between the statues and the plastered skulls. Thus, many follow in her footsteps in viewing the plastered skulls as featuring deceased, revered community members, and consider the statuary as another manifestation of an ancestors cult (Cauvin 1972: 157; Simmons and Boulton, et al. 1990: 109; Akkermans and Schwartz 2003: 98). There is evidence for the use of statues for ancestor worship in the Near East (Katz 2007; 169- 171), but the idea of double-headed or female ancestors exhibiting their breasts is of course not particularly obvious, unless one gives credence to Berossus who wrote in his Babyloniaca that, before time, in the age of darkness, strange men with one body, two heads, and two faces inhabited the sea (Dalley 2002: 117). For these reasons and others, ancestor worship is now being seriously questioned and is visibly running out of steam (Mithen 2004: 37).

In the last century, the periodical Archaeology dubbed the ‘Ain Ghazal statues “Ghosts” (Schuster). This new reinterpretation of the ancestors-cult hypothesis is interesting because the Babylonian cuneiform literature provides ample evidence for the use of substitute figures in ghost rituals (Scurlock 2006: 49; 1995: 94). Three examples will suffice. The first concerns a ghost-expulsion rite (Scurlock 1988: 31-37). When an angry ghost was stalking a person, frightening him/her in his/her dreams (Nemet-Nejat 2007: 256), it was expelled by the means of a substitute figure. The ritual was most propitiously performed between the 27th and the 29th of the month of Abu, the month of August, when the dead were deemed to return to the world of the living. It involved two participants: an exorcist and his patient. The exorcist purified himself and gave appropriate food offerings to gods and ghosts. He then made a figure, which he dressed. He tied magic knots and concocted prescribed potions. The role of the patient involved procuring all necessary ingredients, purifying himself, reciting incantations as directed, holding the figure to the gods, and making libations. The ceremony took place on the roof of the patient’s house, unless the figure was to be sent to the netherworld in a specially prepared boat, in which case the ritual was performed on the canal bank. A third option was to banish the ghost forever by burying the figure in a steppe. All residues from the ritual were also dumped in an abandoned waste area, where they could not hurt anyone (Scurlock 1988: 47).

In the second example, beneficent ghosts were called upon to relieve individuals from their pain by taking it away to the underworld (Scurlock 1988: 120). The ritual for transferring an evil from a patient to a substitute figure involved reciting the appropriate lamentations, covering the head of the figure with a woman’s garment, reciting a prayer, and finally, dressing the figure in a clean garment before anointing it with oil.

The third example is necromancy, which required making a figure of the dead who was being called for divination (Scurlock 1988: 103). In this case it was recommended that the figure be smeared with magic ointments in order to keep the featured ghosts under control (Scurlock 1988: 108).

The texts make clear that substitute figures were rarely destroyed after their final use (Scurlock 1988: 56). Typically, they were buried at sundown, facing west, with a three-day food supply. The effigies of dangerous ghosts were cautiously buried in a pit in the steppe, where they could do no harm (Scurlock 1988: 61).

Because ghosts and sympathetic magic are not unique to Babylon but universal and timeless, (Mithen 1999: 149) it is not inconceivable that the ‘Ain Ghazal figures were used in similar rituals (Moorey 2005: 6-7). This hypothesis would provide a reasonable explanation for a number of characteristic features of the plaster statuary: the large groups of icons, the added garments, the treatment of the surface with color, the manufacture in perishable material, their seemingly brief and ephemeral function, the east-west orientation of the statues and their burial in abandoned areas of the village. The white color, the depth-less bodies, the nose exhibiting the nostrils, the toothless mouth, the odd six-toed feet or hands with four to seven fingers and the feline pupils—all of which could evoke either cadavers, old age or the uncanny—were all perhaps part of a popular depiction of ghosts.

The two interpretations of the function of the figures, either for worship of ancestors or as ghosts, are both very plausible although not entirely convincing (Bayliss 1973; Cassin 1982; Skaist 1980). First, the texts dealing with the manufacture of ghost substitutes prescribe in detail the preparatory magic, such as the purification of the clay pit, the metal offering to contribute, and the precise time to collect the loam. But the only reference concerning the modeling of the figures is a laconic “you pinch the clay,” with no mention of the features to include and the appropriate way to picture them (Scurlock 2006: 132). This suggests that the ghost substitutes were small, skimpy figurines—not large figures involving a complex technology (see Schmandt-Besserat, chapter 4.1). Moreover, two-headed ghosts and female specters exhibiting their breasts seem incongruous.

Second, differences between plastered skulls and statues put the ancestors’ worship theory in question. Kenyon, herself, dismissed her hypothesis observing that, in fact, the contrasts between the two genres were more striking than the similarities (1957: 84). She noted that the statues were flat, less naturalistic and made greater use of paint. She also pointed out that the eyes of the Jericho statues were made of a single shell showing no depiction of the iris, whereas those of the skulls involved several pieces of shell in order to simulate a pupil. Two other facts can yet be added to her list, namely: one skull of Jericho, three at ‘Ain Ghazal, and all those of Tell Aswad have their eyes closed, whereas the statues have theirs always wide open. Lastly, the 1988 plastered skull was located beneath a house floor (Simmons, Boulton, et al. 1990: 108), which indicates that the objects were conceived as beneficent, whereas the statues were isolated in abandoned houses, suggesting that they were feared. This final observation makes it particularly difficult to consider that the two art forms represented the same entities.

Before Kenyon, Garstang was first in volunteering an interpretation for the large plaster statues. He proposed that each of the two sets of three figures he reported excavating in Jericho represented a divine triad: a male, a female, and a child (Kenyon 1957: 85). The two ‘Ain Ghazal caches, with twenty-five and seven statues, respectively, do not corroborate his view. Garstang, however, was not unreasonable in considering a pantheon. Archaeology has amply demonstrated that art the world over (Mithen 1998: 100) and in particular, sculpture in the Near East, from its beginning in the PPNA Khiamian culture to the Babylonian period, is, as a rule, devoted to deities (and in historic times also to royalty) (Spycket 1981). In fact, the monumental size of the ‘Ain Ghazal icons and the possibility that they could be clad with add-on ornaments and displayed on a podium or altar suggest a cult not unlike that known to have been practiced in protoliterate greater Mesopotamia.

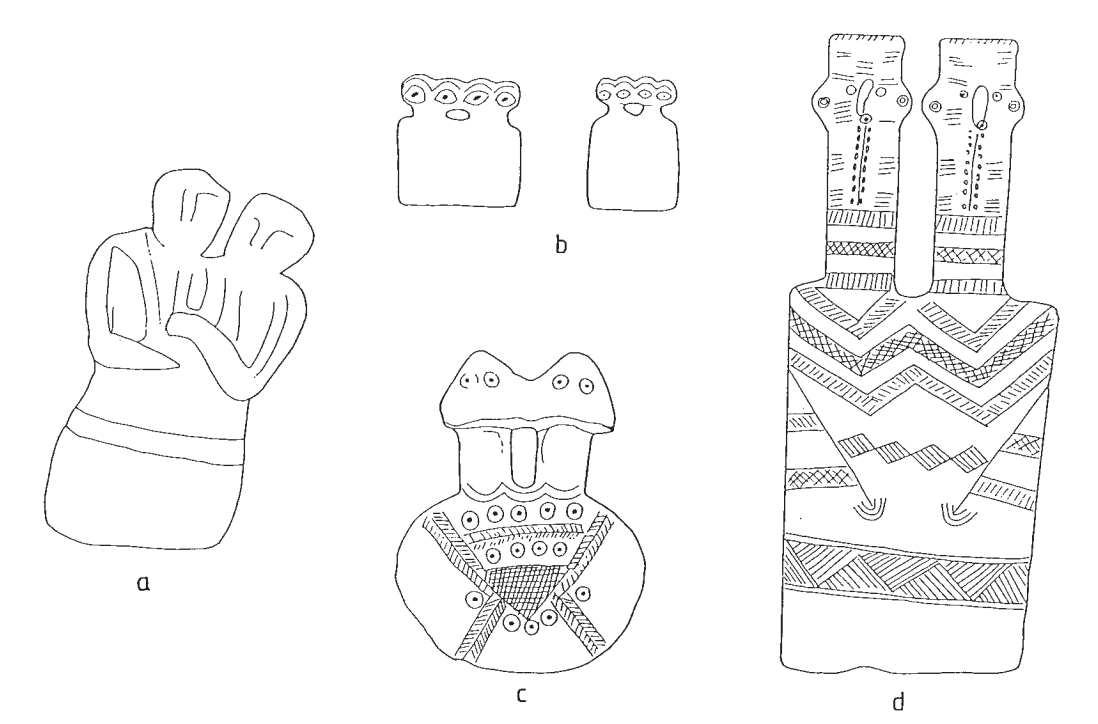

It is particularly noteworthy that the most outstanding figures of the two caches are perfectly familiar in the traditional Near Eastern pantheons. Namely, the two-headed busts find multiple parallels in the long iconography of twin gods or goddesses from Neolithic times to the 3rd millennium bc (Pl. 7.3.2a). For instance, twin figures are featured as small statues and large reliefs in Neolithic Çatal Hüyük (Mellaart 1967: 109, 111, Pl. 70-71). They are part of the assemblage of Hacilar I (Mellaart 1967: 141). Alabaster figurines of Tell Brak warrant that, in the 4th millennium bc, two-headed icons were part of the temple (Mallowan 1947: 133-136, and PL. LI: 19 and 42). Idols with two heads are known in Anatolian (Amiet 1977: 389, Fig. 455) and Cypriot assemblages of the 3rd millennium bc (Karageorghis 1976: Fig. 36). Deities with two, three, and four faces are common features in historic Mesopotamia (Amiet 1977: p. 383, Fig. 431; p. 353, Fig. 221; p. 210, Fig. 84). Finally, there are late textual references concerning the two heads of the greatest of the Babylonian deities: Marduk (Honggeng 2001: 87; Kilmer 2007: 674). The following verses, describing the creation of Marduk in Enuma elish, make it clear that two heads were used as a metaphor to express infinite beauty, omnipresence, and wisdom.

Anu his father’s begetter beheld him,

And rejoiced, beamed; his heart was filled with joy.

He made him so perfect that his godhead was doubled.

… Four were his eyes, four were his ears…

(McCall 1989: 54)

In another translation: “When Ea who begot him saw him, he exulted, he was radiant, light hearted, for he saw that he was perfect, and he multiplied his godhead … with four eyes for limitless sight and four ears hearing all ….” (Sandars 1971: 75-76). Denning-Bolle further notes the importance given to the four ears, the seat of intelligence in Mesopotamia. The following verses of Enuma elish convey that the god’s omniscience depended not only of his four-eyed vision but also the acuteness in hearing of four ears:

They (his features) were impossible to understand (and) difficult to behold.

Four were his eyes, four were his ears.

When he moved his lips, fire blazed forth.

Each of his four ears grew large

And (his) eyes likewise, to see everything.

(Denning-Bolle 1992: 41)

Other texts describe the Assyrian goddess Ishtar as deemed with the same privilege of two-headedness and double breasts: “Istar of Nineveh is Tiamat … she has [4 eyes] and 4 ears” (Livingstone 1986: 233). “Small you were, Assurbanipal, when I left you to the Queen of Nineveh … Four nipples were put in your mouth; two you were suckling, two you were milking” (Stoll 2000: 88).

The most persuasive evidence that the statues may represent deities is the exceptional female emphatically exhibiting two clearly modeled breasts (Pl. 7.3.1a). She folds disproportionately small arms, devoid of forearms, to reach the chest. She stretches her hands in a fan-shape to frame the bosom. The movement is awkwardly rendered. The arms are skimpy, the seven fingers of the right hand are cut sloppily, but nevertheless, the woman revealing her breast while staring sternly at the viewer makes a potent statement.

The female is not unique in executing the striking gesture. It is repeated by two other statues from ‘Ain Ghazal, also from Cache 1. The head and entire left side of the first is destroyed, but a small hand is clearly visible at the chest (Rollefson and Simmons 1985: 30, Fig. 13; Rollefson 1983: 31, Pl. I: 1). In the second, the schematic treatment of the limbs and chest compromise the effect (Pl. 7.3.1b). The figure curves her arms across the torso, but the limbs are reduced to thin, crescent-shaped stumps that fail to reach the breast; there are no fingers pointing to the bosom. Finally, the breasts are thin and minimal. Although the message was probably meant to be the same in the two figures, the first spells it out loud and clear, but in the second it remains ambiguous.

The ‘Ain Ghazal statues may not be the earliest examples of the eye-catching symbol. This distinction may be deserved by two small PPNB Jericho clay figurines of women holding their breasts, found by Kenyon in a shrine (Kenyon 1957: 59). The Jericho examples are precious in bringing the evidence that the motif was already a popular one in the PPNB. After the Neolithic period, the gesture of females cusping their breasts was to enjoy a lifetime of some five millennia in Near Eastern iconography (Moorey 2005: 38, 92, 93, 140, 189, 230, 233). It is repeated from Turkey (Moorey 2005: 35) and the Levant (Badre 1995: 459, Figs. a, b; 460, Figs. a, c-e, g; 461, Figs. a-d; 463, Fig. c; 466, Figs. a-b, g-h; Karageorghis, Fig. 103) to the Zagros Mountains (Spycket 1992: 70-71; 157-179) in innumerable figures until the 1st millennium bc (Pl. 7.3.2b) (Badre 1980: 387, Fig. 32, Pl. LX: 32). The gesture of a female revealing her breasts is generally interpreted as a symbol of nurturing and fertility. It is regarded as the hallmark of Near Eastern goddesses (Badre 1995: 465). The figurines could conceivably represent An’s consort, the goddess An/Antum whose breasts were deemed to be the source of the rain beneficent for vegetation (Jacobsen 1976: 95). The images of females holding their breasts, however, are generally viewed as personifying the goddess of love and fertility revered through the ages under the names of Inanna, Ishtar, Asherath, Astarte, or Tanit (‘Amar: 117). This tradition is supported by hymns preserved in cuneiform texts. Some praise Ishtar as “… the mother of the faithful breast …” or the goddess “… nourishing humanity on her breast …” (Langdon: 60 and 64). Particularly telling is an oracle from Istar of Arbela who assured Esarhaddon “I am your great midwife, your good wet-nurse” (Stol 2000: 88) as well as the following prayer of a king to Inanna to give him her breast, from which he will drink as a symbol of the fertility of the land.

Oh lady, your breast is your field,

Inanna, your breast is your field,

Your wide field which ‘pours out’ plants,

Your wide field which ‘pours out’ grain,

Water flowing from on high-(for) the lord-bread

from on high,

Water flowing, flowing from on high-(for) the lord-

bread, bread from on high,

[Pour] out for the ‘commanded’ lord,

I will drink it from you.

(Kramer: 641-642)

The figures of women exhibiting their breasts can therefore be viewed as metaphors using the every day life experience of a tender mother nursing her child to express the bounty of nature. The greater Mesopotamian world was not unique in translating nature’s prodigality with the image of mother’s milk. Egypt’s vision of abundance was the Pharaoh in full paraphernalia being nursed at the breast of a goddess (Pritchard: 147, Fig. 422). In fact, the most telling picture, commented upon by Pierre Bikai, shows Thutmose III suckled by a tree representing Isis (Bikai: 172 and 401, Fig. 161).

The remarkable gesture unequivocally anchors the ‘Ain Ghazal figures in the ancient Near Eastern divine imagery tradition. Therefore, both the female figures presenting their breasts and the two-headed busts make the balance tip in favor of the pantheon theory. The fact that six figures can be earmarked as divine representations suggests that all the statues of the two caches had a similar significance.

But why would statues of gods and goddesses be discarded all at once and ceremonially buried (Rollefson 2000: 171)? Was it a technical concern, such as the decay of the reed armature or the plaster becoming brittle that required a ritual burying such as described in later texts (Hurowitz 2003: 149)? Or was burial and mourning one of the important aspects of a repetitive, seasonal ritual? Are the statues part of the Near Eastern tradition of dying gods? Do they exemplify the fertility deities displaying death and regeneration that Jacobsen saw as characteristic of agricultural communities and as constituting the substratum of ancient Near Eastern religions (Jacobsen 1974: 1003; McCarter 2007: 160)? Do they presage the annual wailing of Dumuzi or Osiris with their elaborate lamentation rites (Jacobsen 1976: 47-63; Bikai: 149, 156, and 162; Scurlock 1995: 101-102)? If so, the hypothesis would agree with the ephemeral function of the statuary; its manufacture involving short-lived, perishable material; the repeated caches; the ceremonial burial in abandoned areas; and the east-west orientation. It also concurs with the “monumental” size of the figures, the complex material and technology they involved, the add-on headdresses and garments, and particularly, with the evocation of fertility by females presenting their breasts. The symbols of dying gods also explain why the statuary coincided with the establishment of agriculture at the site and subsided with the return to nomadism. According to this hypothesis, the large groups of statues could be interpreted as tutelary deities. Also, gods and goddesses whose function was to die in order to ensure a fertile spring might be expected to borrow features from the dead, such as a fleshless nose. But the meaning of a diamond-shaped iris and other oddities, such as six toes or seven fingers, still remains enigmatic—unless they can be explained as indicative of divine status or simply of poor craftsmanship.

Based on iconography, the ‘Ain Ghazal “monumental” statuary may well have featured mythical protective figures, responsible for life and fertility (Kafafi 1991). The ‘Ain Ghazal statues are testimonies to the everlasting endurance of symbolism (Hinde 2007: 325; Mithen 1998: 103). In particular, the two-headed icons and the females clutching their breasts provide the evidence that the forceful images of all-seeing beings and goddesses nursing mankind had their roots in the Neolithic as early as 6500 bc. In fact, the symbol of the motherly nourishment may be viewed as a creation typical of the beginning of agriculture. There is little doubt that fertility acquired a new pressing significance when the survival of sedentary populations depended on the production of fields and orchards. It is therefore to be expected that new deities emerged in the farmers’ pantheon, followed by new rituals that were meant to insure bountiful harvests and prosperous flocks. The gesture of the female exhibiting her breasts was a potent symbol fostering a new ideology (Bar-Yosef and Meadow 1995: 80) that already presaged the cult of Inanna. Further traits that persisted in statuary through the ebb and flow of religions from prehistory to history are worth repeating here: large figures with add-on headdresses and garments, two-headed gods, goddesses presenting their breasts, and finally, dying deities as being the key to fertility.

Conclusion: The Significance

Except for satisfying our curiosity, whether the statues stood for deities, ancestors or ghosts is, in fact, almost inconsequential. The uniqueness of the statuary is its monumentality (Renfrew 2007: 123). Its true significance is in revealing a major step in the manipulation of symbolism: from domestic figurines to public statues. Since symbols are instruments of thought allowing people to conceive and share ideas (Boyer 2001: 237; Mithen 1999: 165; Renfrew 1998: 6); the size of the group they impact is of crucial importance. Whereas the former, modest PPNA figurines of the Khiamian culture were experienced by few, the statues reached multitudes. Their large size, stylized features, and, probably, bright add-on garments made it possible for the icons to be seen by an entire community and, consequently, for an entire community to partake actively in common rites. In other words, the monumental statuary was instrumental in the shift from domestic to public ritual.

It is up to archaeology to envision the cultural, social, political, and economic consequences of the large, standardized statuary (Kuijt 2000: 154). Public rituals, no doubt, restructured reality in the agricultural communities. They established which seasonal events to celebrate, such as the harvest or the new year, thus creating fixed dates and a common time (Durkheim: 443); they ruled the deities to be worshipped and the appropriate way to do so. Socially, the festivals associated with the creation or ceremonial burial of the figures brought the community together in an unprecedented way. The powerful feelings generated by prostrating in front of the icons, marching in procession, and singing in chorus increased the sense of belonging and built solidarity. Cultic ceremonies also had an important political function. They involved all members of the community from elders to youth, defining the status of each group by the part it fulfilled in the liturgy (Kertzer: 9). Mostly, the festivals bolstered authority. The public ceremonies singled out the leaders by their proximity to the icons, the special garb and headdress they wore, the solemn gestures they performed and the potent utterances they pronounced. Finally, the seasonal celebrations had an economic impact by attracting people from neighboring villages, thus increasing trade. The rituals entailed feasting that required developing ways of pooling communal resources, as well as counting, recording, budgeting, and administrating vast quantities of real goods (Schmandt-Besserat 1992: 184-194).

Monumental statuary was an outcome of agriculture. The statues were created to bond the large population supported by farming. The monumental figures were powerful symbols that helped foster a common ideology, restructure society, enhance leadership and amplify the need for administrating the communal resources in the early agricultural communities. These important developments eventually paved the way for state formation.

Acknowledgments:

The study was funded by a fellowship from the American Center of Oriental Research, Amman, Jordan and a grant from the Near and Middle East Research and Training Act (NMERTA). An earlier version of the paper was published in 1998 in The Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 310: 1-17.

Bibliography

Akkermans P.M.M.G. and Schwarz G.M.

2003 – The Archaeology of Syria, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amiet P.

1977 – The Art of the Ancient Near East. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Amiran R.

1962 – Myths of the creation of man and the Jericho statues. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 167: 23-24.

‘Amr A.J.

1980 – A Study of the Clay Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels of Trans-Jordan During the Iron Age, with Special Reference to Their Symbolism and Function. London, University of London: Ph.D. Dissertation.

Badre L.

1980 – Les Figurines Anthropomorphes en Terre Cuite à l’Age du Bronze en Syrie. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.

1995 – The terra cotta anthropomorphic figurines. In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan. V. Amman: Department of Antiquities.

Bar-Yosef O.

1980 – A human figurine from a Khiamian site in the Lower Jordan Valley. Paleorient 6: 193-199.

Bar-Yosef O. and Alon D.

1988 – Nahal Hemar cave. ‘Atiqot. English Series XVIII: 1-30.

Bar-Yosef O. and Meadow R.H.

1995 – The origin of agriculture in the Near East. In T.D. Price and A.B. Gebauer (eds), Last Hunters, First Farmers: New Perspectives on the Prehistoric Transition to Agriculture: 39-94. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Bayliss M.

1973 – The cult of dead kin in Assyria and Babylonia. Iraq 35: 115-125.

Bikai P.M.

1993 – The Cedar of Lebanon: Archaeological and Dendrochronological Perspectives. Berkeley, University of California: Ph.D. Dissertation.

Boyer P.

2001 – Religion Explained. New York: Basic Books.

Cassin E.

1982 – Le mort: valeur et représentation en Mesopotamie ancienne. In G. Gnoli and J.P. Vernant (eds.), La Mort, les morts dans les sociétés anciennes: 355-372. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cauvin J.

1972 – Les Religions Néolithiques de Syro-Palestine. Paris: Maisonneuve.

Dalley S.

2002 – Evolution of gender in Mesopotamian mythology and iconography with a possible explanation of Sha Reshen, “the man with two heads.” In S. Parpola and R.M. Whiting (eds.), Sex and Gender in the Ancient Near East. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki: Institute for Asian and African Studies, University of Helsinki: 117-122.

Denning-Bolle S.

1992 – Wisdom in Akkadian Literature. Leiden: Ex Oriente Lux.

Durkheim E.

1980 – The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (2nd edition). London: George Allen and Unwin.

Garfinkel Y.

2009 – The transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic in the southern Levant: the material culture sequence. In J.J. Shea and D.E. Lieberman (eds.), Transitions in Prehistory, Essays in Honor of Ofer BarYosef: American School of Prehistoric Research Monograph Series: 325-333. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Garstang J.

1935 – Jericho: city and necropolis (5th report). Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 22/3-4: 143-184.

Garstang J. and Garstang J.B.E.

1948 – The Story of Jericho (2d edition). London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, Ltd.

Goren Y. and Segal I.

1995 – On early myths and formative technologies: a study of PPNB sculptures and modeled skulls from Jericho. Israel Journal of Chemistry 35/2: 155-165.

Goren Y., Segal I., and Bar-Yosef O.

1993 – Plaster artifacts and the interpretation of the Nahal Hemar cave. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society 25: 120-131.

Grissom C.A.

1996 – Conservation of Neolithic lime plaster statues from ‘Ain Ghazal. In R. Ashok and P. Smith (eds.), Archaeological Conservation and Its Consequences: 70-75. London: The International Institute for Conservation of Historic Artistic Works.

Gunther A.

1995 – Preserving Ancient Statues from Jordan (exhibition brochure). Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Hinde R.A.

2007 – The worship and destruction of images. In C. Renfrew and I. Morley (eds.), Image and Imagination. McDonald Institute Monographs: 323-331. Exeter: Short Run Press.

Hole F.

2000 – Is size important? function and hierarchy in Neolithic settlements. In I. Kuijt (ed.), Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: 191-209. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Honggeng G.

2001 – The Mysterious Four-Faced Statue (OIM A719). Journal of Ancient Civilizations. 16: 87-91).

Hurowitz V. A.

2003 – The Mesopotamian God Image, From Womb to Tomb. Journal of the American Oriental Society 123.1: 147-157.

Jacobsen T.

1973 – Mesopotamian religions. In Encyclopedia Britannica: 1001-1006. Chicago: Helen Hemingway Benton, Publisher.

1976 – The Treasures of Darkness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kafafi Z.

1991 – The role of women in the Stone Age: preliminary ideas (in Arabic). Newsletter of the Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Yarmouk University 11: 12-14.

Karageorghis V.

1976 – The Civilization of Prehistoric Cyprus. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon S.A.

Katz D.

2007 – Sumerian funerary rituals in context. In N. Laneri (ed.), Performing Death: Social Analyses of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Oriental Institute Seminars 3: 167-188. Chicago: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

Kenyon K.M.

1957 – Digging Up Jericho. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Kertzer D.I.

1988 – Ritual, Politics and Power. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kilmer A.D.

2007 – The Horses and Other Features of Marduk’s Attack Chariot (EE IV) and Comparanda. Journal for Semitics 16/3: 672-679.

Kingery W.D., Vandiver P.B., and Prickett M.

1988 – The beginnings of pyrotechnology, part II: production and use of lime and gypsum plaster in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Near East. Journal of Field Archaeology 15/2: 219-244.

Kramer S.N.

1969 – Dumuzi and Inanna: prayer for water and bread. In J.B. Pritchard (ed.), Ancient Near Eastern Texts relating to the Old Testament: 641-642. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kuijt I.

2000 – Keeping the peace: ritual, skull caching, and community integration in the Levantine Neolithic. In I.Kuijt (ed.), Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: 137-162. New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers.

Kuijt I. and Chesson M.S.

2007 – Imagery and social relationships: shifting identity and ambiguity in the Neolithic. In C. Renfrew and I. Morley (eds.), Image and Imagination. McDonald Institute Monographs: 211- 226. Exeter: Short Run Press.

Langdon S.

1914 – Tammuz and Ishtar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Livingstone A.

1986 – Mystical and Mythological Explanatory Works of Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McCall H.

1988 – Mesopotamian Myths. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

McCarter S.F.

2007 – Neolithic. London: Routledge.

Mallowan M.E.L.

1947 – Excavations at Brak and Chagar Bazar. Iraq 9: 1-259.

Mellaart J.

1967 – Catal Hüyük, A Neolithic Town in Anatolia. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mithen S.

1998 – The supernatural beings of prehistory and the external storage of religious ideas. In C. Renfrew and C. Scarre (eds.), Cognition and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Symbolic Storage. McDonald Institute Monographs: 97-106. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

1999 – Symbolism and the supernatural. In R. Dunbar, C. Knight, and C. Power (eds.), The Evolution of Culture: 147-169. Edinburgh: Edinburg University Press.

2004 – From Ohalo to Catalhoyuk: the development of religiosity during the early prehistory of western Asia, 20,000-7000 BCE. In H. Whitehouse and L.H. Martin (eds.), Theorizing Religions Past: 17- 43. New York: Altamira Press.

Moorey P.R.S.

2005 – Ancient Near Eastern Terracottas: Oxford: Oxford University, Ashmolean Museum.

Nemet-Nejat K.R.

2007 – Religion of the common people in Mesopotamia. Religion Compass 1-2: 245-259.

Nissenbaum A.

1996 – 8000 years collagen from Nahal Hemar cave (in Hebrew). Archaeology and Natural Sciences 5: 5-9.

Pritchard J.B.

1967 – The Ancient Near East in Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Renfrew C.

1996 – Mind and matter: cognitive archaeology and external symbolic storage. In C. Renfrew and C. Scarre (eds.), Cognition and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Symbolic Storage. McDonald Institute Monographs: 1-6. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

2007 – Monumentality and presence. In C. Renfrew and I. Morley (eds.), Image and Imagination. McDonald Institute Monographs: 121-133. Exeter: Short Run Press.

Rollefson G.O.

1982 – Ritual and ceremony at Neolithic ‘Ain Ghazal (Jordan). Paléorient 9/2: 29-37.

2000 Ritual and social structure at Neolithic ‘Ain Ghazal. In Ian Kuijt (ed.), Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: 165-209. New York: KluwerAcademic/Plenum Publishers.

2005 – Early Neolithic ritual centers in the southern Levant. Neo-Lithics 2: 3-13.

2008a – Charming lives: human and animal figurines in the Late Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic periods in the Greater Levant and eastern Anatolia. In J.P. Bocquet-Appel (ed.), The Neolithic Demographic Transition and its Consequences: 387-416. New York: Springer.

2008b – The Neolithic period. In R.B. Adams (ed.), Jordan, An Archaeological Reader: 71-108. London: Equinox.

Rollefson G.O. and Kafafi Z.

2007 – The rediscovery of the Neolithic period in Jordan. In T.E. Levy, P.M.M. Daviau, R.W. Younker, and M. Shaer (eds.), Crossing Jordan: 211-218. London: Equinox.

Rollefson G.O. and Kohler-Rollefson I.

1989 – The collapse of early Neolithic settlements in the southern Levant. In I. Hershkovitz (ed.), People and Culture in Change. British Archaeological Reports – Intern. Series 508/1: 73-89. Oxford: B.A.R.

Rollefson G.O. and Simmons A.H.

1985 – The early Neolithic village of ‘Ain Ghazal, Jordan: preliminary report on the 1983 season. Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research Supplement 23: 35-52.

1987 – The Neolithic village of ‘Ain Ghazal, Jordan: preliminary report on the 1985 season. Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research Supplement 25: 93-106.

Rollefson G.O., Simmons A.H., and Kafafi Z.

1992 – Neolithic cultures at ‘Ain Ghazal, Jordan. Journal of Field Archaeology 19/4: 443-470.

Sandars N.K.

1971 – Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Schmandt-Besserat D.

1992 – Before Writing, Vols. 1 and 2. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

Schuster, A.H.M.

1995 – Ghosts of ‘Ain Ghazal. Archaeology 49/4: 65-66.

Scurlock J.

1988 – Magical Means of Dealing with Ghosts in Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago, University of Chicago: Ph.D. Dissertation.

1995 – Magical uses of ancient Mesopotamian festivals of the dead. In M. Meyer and P. Mirecki (eds.), Ancient Magic and Ritual Power: 93-107. Leiden: Brill.

2006 – Magico-Medical Means of Treating Ghost-Induced Illnesses in Ancient Mesopotamia. Leiden: Brill-Styx.

Simmons A.H., Boulton A., Roetzel Butler C., Kafafi Z., and Rollefson G.O.

1989 – A plastered human skull from Neolithic ‘Ain Ghazal, Jordan. Journal of Field Archaeology 17/1: 107-110.

Skaist A.

1980 – The ancestor cult and succession in Mesopotamia. In B. Alster (ed.), Death in Mesopotamia: 123- 128. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Spycket A.

1980 – La Statuaire du Proche Orient Ancien. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

1992 – Les Figurines de Suse. Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique en Iran 52. Paris: Editions Paul Geuthner.

Stol M.

2000 – Birth in Babylonia and the Bible: Its Mediterranean Setting. Groningen: Styx.

Tubb K.W. and Grissom C.A.

1995 – ‘Ayn Ghazal: a comparative study of the 1983 and 1985 statuary caches. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan: 437-447. V. Amman: Department of Antiquities.

Yakar R. and Hershkovitz I.

1987 – Nahal Hemar cave, the modeled skulls. ‘Atiqot. English Series XVIII: 59-63.

Page last updated: 1/19/20