![]() Download the PDF (548 KB)

Download the PDF (548 KB)

Read on Texas Scholar Works

By Denise Schmandt-Besserat

Abstract: The paper analyses the development of the power of abstraction as illustrated by the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Tokens indicate that counting was first done concretely in one-to-one correspondence. The clay tokens, which were used at ‘Ain Ghazal about 7250-6500 bc, abstracted the goods they represented. For example, a cone abstracted a measure of grain. About 3300 bc, when tokens were kept in envelopes, markings on envelopes abstracted the tokens held inside. Abstract numbers are the culmination of the process, following the invention of writing.

Key Words: token, counting, writing, cognitive archaeology, abstraction

Traditional archaeology aims at reconstructing the culture, economy, and technology of past societies. In recent years cognitive archaeology has added a new dimension to our investigation of antiquity by focusing upon artifacts documenting the development of cognitive skills. Foremost among these objects, the Near Eastern prehistoric tokens and the earliest archaic tablets, exemplify the gradual mastery of the power of abstraction necessary to achieve numeracy and literacy (Malafouris 2010).

Archaeological sites, such as ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan, are called “Tell” in Arabic and “mounds” in English. The mounds are artificial hills formed by the accumulation of debris over the centuries, or millennia, as a result of human occupation. In other words, they are the accumulation of remains of villages upon villages or towns upon villages. The excavators give prime attention to the architectural features unearthed in the mounds in order to estimate the size and lay out of the settlements and the way of life at the site. For example, the foundations of buildings at ‘Ain Ghazal give evidence that the first settlers were sedentary, but in time the community changed to nomadism. Organic materials discarded in antiquity, such as bones and charred ears of grains, are carefully studied because they disclose not only the people’s diet but their economy. Namely, the first occupants of ‘Ain Ghazal were farmers, but the last had become pasturalists. Other artifacts indicate the degree of technology reached by a community. For instance, the tools of ‘Ain Ghazal were made exclusively by chipping or grinding stone. Animal and anthropomorphic gurines suggest magic rituals, while statuettes, plastered skulls and statuary evoke the beliefs of the Neolithic society.

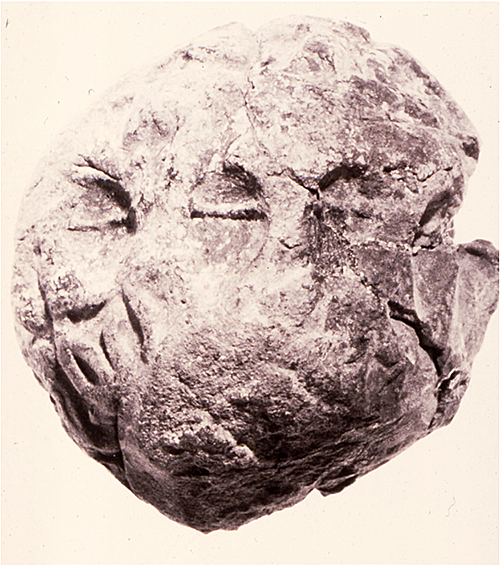

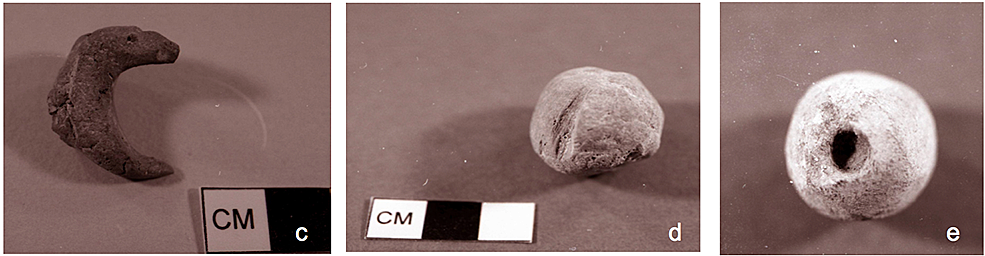

In contrast to the above artifacts, the tokens I studied are unique in providing evidence for the development of cognitive skills between 7500-3000 bc. The objects, made of clay, and modeled into many shapes such as miniature cones, spheres, cylinders, disks and crescents, were counters (Fig. 2.3.1). They were tools of the mind, and as such, give us insights on human cognition. In particular, the tokens give information on numeracy—the way of counting practiced at ‘Ain Ghazal and in the various other cultures that adopted them.

The Function of Counting in Prehistory

Before dealing with the cognitive significance of the token system, I first discuss its origin and cultural background. Tokens started to appear in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, from Jordan to Iran, around 7500 bc, concurring with the domestication of plants in the region (Schmandt-Besserat 1996). This means that counting coincided with farming and the redistribution economy that derived from it. Tokens, most probably, were used to pool together community surpluses. The tokens most likely helped leaders to keep track of the goods in kind collected and their redistribution as offerings to the gods, the preparation of festivals and various community needs.

The Cognitive Significance of Tokens

The tokens used a way of counting fundamentally different from ours. They were used in one-to-one correspondence. Two jars of oil were shown by two ovoids and three jars of oil were marked by three ovoid tokens. Moreover, we use abstract numbers, which means that our numbers “one,” “two,” “three,” are independent of the item counted and therefore universally applicable. “One,” “two,” “three” can serve to count people, animals as well as inanimate objects, and anything else possible. It was not so at the time when tokens were used. Between 7500-3100 bc, counting was restricted to determine the number of selected units of goods, mostly measures of grain, jars of oil and animals. Each category of merchandise was counted with its own counter, re ecting the fact that counting was “concrete.” In other words, in the absence of abstract numbers applicable to any item, each category of goods was counted with special number words or their corresponding specific counters. For examples, the cones and spheres, the most frequent types of tokens recovered at ‘Ain Ghazal, represented small and large units of grain (Pl. 2.3.1a and b) while the ovoids were used to count jars of oil. A token in the shape of a crescent unknown elsewhere suggest a unique merchandise available exclusively at the site (Pl. 2.3.1c) (see Iceland, chapter 2.1).

The tokens were well established in the 8th millennium bc and remained in continuous use over four millennia. Over the centuries their evolution illustrates the unceasing cross-fertilization that took place between the redistribution economy’s increasing demands and the development of counting. For example, at ‘Ain Ghazal, there were no more than six types of tokens, and twenty-three subtypes, created by varying the basic size and shape of the artifacts or by adding markings such as groves and dots (Pl. 2.3.1d and e) (see Iceland, chapter 2.1). But about 3300 bc, in such cities as Uruk in Mesopotamia, when urban workshops started contributing to the redistribution economy, the number of token types had increased to fifteen and the subtypes to 350. Some of the new tokens stood for raw materials such as wool and metal while others represented finished products, among them textiles, garments, jewelry, bread, beer, and honey (Fig. 2.3.2). These so-called “complex” tokens sometimes assumed the shapes of the items they symbolized such as garments, miniature vessels, tools and furniture. These artifacts took far more skill to model compared to the former geometric shapes such as cones and spheres, suggesting that specialists were then manufacturing them (Schmandt-Besserat 1992).

The Transition from Tokens to Writing

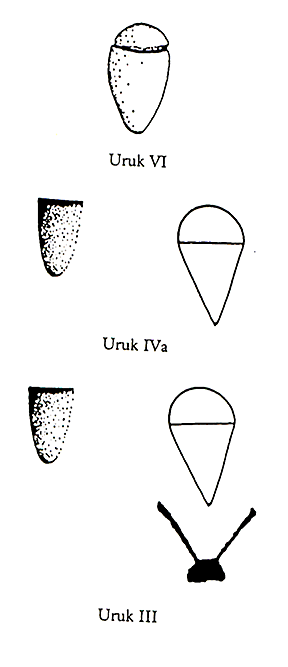

By 3300 bc, tokens were still the only accounting device to manage the redistribution economy that was now administered at the temple by priestly rulers. The communal offerings in kind for the preparation of festivals continued, but the types of goods, their amounts, and the frequency of delivery to the temple became regulated, and non-compliance was penalized. The response to the new challenge was the invention of envelopes where tokens representing a delinquent account could be kept safely until the debt was paid. The tokens standing for the amounts due were placed in hollow clay balls and, in order to show the content of the envelopes, the accountants created markings by impressing the tokens on the wet clay surface before enclosing them. The ovoid tokens with a grove across became a negative oval with a positive ridge across (Fig. 2.3.3). Within a century, about 3200 bc, the envelopes filled with counters and their corresponding signs were replaced by solid clay tablets, which continued the system of signs impressed with tokens. The cones and spheres symbolizing the measures of grain became wedge-shaped and circular-impressed signs on the tablets (Fig. 2.3.4). By innovating a new way of keeping records of goods with signs, the envelopes created the bridge between tokens and writing.

Tablets and Counting

With the formation of city-states, ca. 3200-3100 bc, the redistribution economy reached a regional scale. The unprecedented volume of goods to administer challenged writing to evolve in form, content and, as will be discussed later, in cognitive ability. First, about 3100 bc, the form of the signs changed when a pointed stylus was used to sketch more accurately the shape of the most intricate tokens and their particular markings. The sign for oil, for example, reproduced the ovoid token with its circular line at the maximum diameter (Fig. 2.3.5).

Second, plurality was no longer indicated by one-to-one correspondence. The number of jars of oil was not shown by repeating the sign for “jar of oil” as many times as the number of units to record. The sign for “jar of oil” was preceded by numerals—signs indicating numbers. Surprisingly, no new signs were created to symbolize the numerals but rather the impressed signs for grain took on a numerical value. The wedge that formerly represented a small measure of grain came to mean “1” and the circular sign, formerly representing a large measure of grain meant “10.” Figure 2.3.5 illustrates an account of thirty-three jars of oil indicated by three circular impressed signs (10 + 10 + 10) and three impressed wedges (1 + 1 + 1) followed on the right by the incised sign for “jar of oil.”

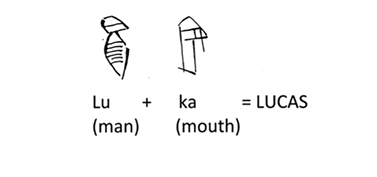

Third, about 3000 bc, the state bureaucracy required that the names of the recipients or donors of the goods be entered on the tablets. And to record the personal name of these individuals, new signs were created that stood for sounds—phonograms. The phonograms were sketches of things easy to draw that stood for the sound of the word they evoked. The syllables or words composing an individual’s name were written like a rebus. The drawing of a man stood for the sound “lu” and that of the mouth for “ka,” which were the sounds of the words for “man” and “mouth” in the Sumerian language. For example, the modern name Lucas, could have been written with the two signs mentioned above “lu-ka” (Fig. 2.3.6).

The state administration could no longer deal with the approximate quantities of informal containers and this prompted the standardization of measures. The resulting adjustment in accounting was to assign new signs to indicate the standard measures of grains (ban, bariga, etc.), liquids (sila), and surface areas (ikus, eshe3, bur, etc.) (Nissen et al. 1993: 28-29). The standardization of measures brought accounting to an unprecedented precision, while putting an end to dealing with informal hand-manufactured containers (Fig. 2.3.7).

During four millennia and a half, from 7500 to 3000 bc, tokens and writing constituted the backbone of the Near Eastern redistribution economy. Both recording systems were closely related in material, form, and function. They shared clay as a raw material; the token shapes were perpetuated by the written signs; both types of symbols kept track of similar quantities of the same types of agricultural and industrial goods for an identical socio-economic function. The difference between the systems was cognitive, namely the degree of abstraction used to manipulate data.

Tokens and Abstraction

The major cognitive significance of the tokens was fostering abstraction. The fundamental principle of the token system was the substitution of a small clay counter for each unit of goods to be counted. As a result, merchandise could easily be counted and accounted for because the tokens abstracted goods from reality.

- Tokens abstracted the bulk and weight of merchandise so that heavy loads of grain could be effortlessly computed.

- Tokens abstracted life or movement, thus allowing unruly animals, dif cult to control, to be easily registered.

- The tokens abstracted time, making it possible for the Near Eastern accountants to manage goods whether they were still in the eld or stored in the granary, and whether they were pledged or delivered.

- The Near Eastern accountants could perform simple and complex operations just by moving or removing tokens. For example, they could add, subtract, multiply, and divide.

- Patterning, the presentation of data in lines and columns, further

promoted abstraction (Justus 2004 and 1999; Hoyrup 1994). With tokens,

the Near Eastern accountants could organize the budget for a festival in columns according to- Types of goods

- Entries and expenditures

- Donors or recipients

- Goods symbolized by tokens could be lined up according to their relative value

- Large units above

- Small units below

In sum, the invention of tokens in the Near East, about 7500 bc, had reached ‘Ain Ghazal by 7000 bc providing a useful tool to manage communal goods. There can be no doubt that people acquired new cognitive skills by using tokens over 4500 years to count and recount sheep and baskets of grain in abstraction. When these cognitive skills had been internalized for several millennia, the human mind was ready for new strides in abstraction. Concrete counting with tokens was the necessary foundation for the invention of writing.

Writing and Abstraction

Writing meant three extraordinary developments in abstraction that occurred in close succession, probably within the century between 3100-3000 bc. These abstractions concerned the creation of 1) two-dimensional signs, 2) abstract numerals, and 3) phonetic signs. The magnitude of these strides in the mastery of abstraction can be realized by comparing and contrasting the degree of abstraction between tokens and writing.

- The tokens were tangible but the signs of writing were intangible. They abstracted the tokens that abstracted goods. The awkward piles of three-dimensional tokens could disappear.

- The tokens were used in one-to-one correspondence but writing abstracted numbers.For the first time, signs expressing numerals abstracted the concept of number from that of the item counted. For example, a sign for “one” was placed next to the sign for “jar of oil.”The invention of abstract numerals made obsolete the use of different counters and numerations to count different products. With the abstraction of numbers, counting had no limit.

- The tokens were strictly limited to representing concrete units of real goods, whereas writing abstracted immaterial sounds of speech. The phonetic syllabic signs used to record individuals’ names started the process of emulating speech. As a result, writing was no longer con ned to recording goods but could strive to communicate the most abstract ideas.

Conclusion

The modest tokens of ‘Ain Ghazal were designed to count staple goods. The token system endured during four and one half millennia in the ancient Near East. It evolved to compute in abstraction an ever-greater volume of more and more complex data, and thereby paved the way to writing. Cognitive archaeology makes it clear that the immense value of the tokens was to bring the human brain to the level of abstraction necessary for literacy and civilization.

Acknowledgments: An earlier version of the chapter was published in 2009 in Scripta 1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hoyrup J.

1994 In Measure, Number, and Weight. New York: State University of New York Press.

Justus C.

1999 Pre-decimal structures in counting and metrology. In J. Gvozdanovic (ed.), Numeral Types and Changes Worldwide. 55-79. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

2004 On language and the rise of a base for counting. General Linguistics 42: 17-43.

Malafouris L.

2010 Grasping the concept of number: how did the sapient mind move beyond approximation? In I. Morley and C. Renfrew (eds.), The Archaeology of Measurement. 35-42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nissen H.J., Damerow P., and Englund R.K.

1993 Archaic Bookkeeping. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Schmandt-Besserat D.

1992 Before Writing, Vols. 1 and 2. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

1996 How Writing Came About. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

2010 The token system of the ancient Near East: its role in counting, writing, the economy and cognition. In I. Morley and C. Renfrew (eds.), The Archaeology of Measurement. 27-34. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2011 Chirographic culture. In P.C. Logan (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language Sciences. 154-157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1 The dates mentioned in this chapter are expressed as non-calibrated radiocarbon dates, reflected by the use of the lowercase “bc” referent.

Page last updated: 1/25/20